Katharine of Aragon

Katharine was born in Alcala de Henares, Spain on the night of 15 – 16 December 1485. She was the fifth and youngest child of the ‘Catholic Kings’ , Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. The marriage of Katharine’s parents, whilst not formally uniting their respective countries had created a new and powerful European kingdom of Spain. It was the goal of these monarchs, to increase Spanish power both within the peninsula itself by reconquering the Moorish kingdom of Granada and abroad through pressing Aragonese claims to Naples. Most importantly, they sought to prevent a newly powerful France from dominating Italy.

A key component of the sovereigns’ strategy was the marital alliances that they arranged for their children. Katharine, as fourth daughter, was of perhaps less political importance and therefore her betrothal in 1489 to the son of Henry VII of England was in the nature of a gamble. Henry had only established himself as King of England from the Wars of the Roses in the year of Katherine’s birth and in 1489 it was still a possibility that the fledgling Tudor dynasty might be overthrown.

Nevertheless in the Treaty of Medina del Campo 1489 it was agreed that Katherine would marry Arthur, Prince of Wales, and would travel to England when she was 14. Over the following ten years further negotiations took place and the young couple were married by proxy.

Katharine’s brother, Juan, had been married at the age of 17 to Marguerite of Austria. Their respective siblings, Juana, and Philip, Duke of Burgundy, were also married. Juan and Marguerite took to married life with gusto and when the young man died within six months his demise was, in part, attributed to too much sexual exertion at a young age. The shock of this death and the grief that it caused to the Spanish Royal family should not be overlooked in considering Katharine’s own marital history.

The Spanish Princess left Spain in autumn 1501, arriving at Plymouth on 8 th October. Travelling slowly towards London, the party was met at Dogmersfield in Hampshire by Henry VII and Prince Arthur, who had been summoned from Ludlow where he was presiding over the Council of Wales. Arthur had turned 15 on 20 th September.

The couple, unable to converse other than in Latin, were briefly introduced before etiquette demanded that the bride be kept separate from her groom until the wedding day. Katharine was lodged at Lambeth Palace in London until the wedding was celebrated at St Paul’s Cathedral on 14 th December. She was led to the altar by her groom’s 10-year-old brother, Henry, Duke of York.

The marriage of the young couple was extremely popular in both court and country. The festivities to mark the occasion were lavish and continued with jousting, feasting and dancing. Arthur himself had either little taste or little energy for dancing, performing only once, whilst the Duke of York showed himself as a boisterous performer.

As was customary the young couple were put to bed in public, well aware that their primary duty was to produce sons to inherit the English throne. Not long after the marriage it was decided that Arthur should return to his duties in the Marches of Wales and there was some debate as to whether Katharine should accompany him. It was not uncommon for a young couple to consummate the marriage once and then be separated as too much sexual activity at a young age was believed injurious to the health. Eventually it was decided that Katharine should go.

By March Arthur was seriously ill and he died on 2 April 1502. Katharine returned to London and debate began as to her future. Initially Queen Isabella wanted her daughter to return home but Henry VII was reluctant to see the vast jointure that Katherine would have been entitled to of one third of the revenues of the principality of Wales and the Duchy of Cornwall sailing away – particularly as he had not yet received the whole of Katharine’s dowry.

A marriage was mooted for Katharine with the young Duke of York – some five and a half years younger than her. For such a marriage a papal dispensation was necessary, the type depending on whether or not the first marriage had been consummated. Initially there was doubt as to the status of Katharine’s virginity as Katharine’s confessor and her principal lady, Doña Elvira Manuel, gave conflicting accounts.

The Spanish Sovereigns believed Doña Elvira, and wrote clearly that although Katharine was a virgin, they would request a dispensation covering the case of consummation because they feared that at a later date the English King might try to wriggle out of the bargain. The initial dispensation gave consent for Katharine and Henry to marry on the assumption that she had consummated her marriage to his brother whilst an accompanying Papal brief that appears only to have been dispatched to Spain enlarged on this with the insertion of the words ‘perhaps consummated’.

Despite the agreement, Henry VII dragged his feet and Ferdinand and he continued to quarrel over Katharine’s dowry. In 1504 Queen Isabella died, and the crowns of Spain broke apart as her daughter, Juana, Duchess of Burgundy inherited. It soon became apparent that Juana’s husband Philip intended to dominate both his wife and Castile, to the detriment of Ferdinand’s position.

Katharine’s position became increasingly difficult as she did not have sufficient funds to maintain her household without encroaching on plate and jewels that Henry VII claimed were a part of her dowry and she lived a miserable existence, sending increasingly emotional letters to her father requesting help, which Ferdinand largely ignored.

The marriage between Katharine and Henry should have taken place in 1505 when Henry reached 14, the age of consent for a boy. The prince made a formal retraction of his betrothal as it had been made during his minority. Nevertheless negotiations for a marriage continued to take place.

The Gordian knot was finally cut in 1509 when Henry VII died. Within a few weeks of becoming King the young Henry had married Katharine and the two were crowned together on 24 th June 1509. Over the next few years Henry and Katharine appear to live an almost idyllic life as a happy young couple in the first flush of love and power. They danced and hunted vigorously, patronised musicians and scholars.

The couple were also politically close as Henry, seeking to establish himself as a new Henry V, allied with Ferdinand of Aragon to invade France. Before Henry led his army in France, he appointed Katharine as Regent – a role she carried out extremely effectively, including working with the Earl of Surrey to repel the invasion of James IV of Scotland, who as the ally of France had invaded northern England. James was defeated at Flodden in one of England’s most comprehensive victories against its northern neighbour and Katharine identified herself very closely with it.

Unfortunately, matters did not go quite so well in France. Although Henry won territory – the first territory won by the English in France since 1453, it was of little strategic value and he was routinely let down by Ferdinand. Ferdinand’s behaviour undoubtedly weakened Katherine’s political influence, which gradually began to be replaced by that of Henry’s minister, Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal and Archbishop of York.

Wolsey was by nature opposed to war – it was costly and wasteful. He looked for peace and political alliances, including with the French, whom Katharine had been brought up to see as the enemy. Katharine resented his influence, personally and politically.

Another problem was creeping into the royal marriage – the lack of children. Katharine became pregnant within a few weeks of her marriage but miscarried a daughter in early 1510. A son was born on 1 st January 1511, Henry Duke of Cornwall, but he died within two months. There were probably one or two further miscarriages or stillbirths before Katharine finally gave birth to a child who would survive to adulthood – Mary, born 18th February 1516. A final pregnancy in 1518 resulted in a stillborn daughter.

By 1525, Henry had concluded that there would be no more children – although she was barely 40 Katharine seems to have reached the menopause and had not conceived in seven years.

For Henry, only the second in his dynasty, to have a son was his paramount duty. Despite the example of Katharine’s mother, Isabella of Castile, and the very successful regencies of Anne of Beaujeu in France and Katharine’s sister-in-law, Marguerite of Austria, in the Netherlands, the idea of a woman sovereign was unacceptable to the King. He had had an illegitimate son in 1519 and from this he inferred that he was capable of having healthy sons and that there must be another problem afflicting his marriage to Katharine.

Two other events now occurred that created the perfect storm for Katharine’s marriage. In 1526 her nephew, now King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, who had been betrothed to Princess Mary, broke off the match to marry her niece, Isabella of Portugal. The alliance that Katharine represented had become politically worthless. And, in an event much closer to home, Henry had fallen violently in love with Katharine’s maid-of-honour, Anne Boleyn.

Henry now sought to be released from his marriage with Katharine. It would be unfair to Henry to suggest that his concern that he had broken God’s law by marrying his brother’s wife was completely cynical, only trumped up to rid himself of unwanted spouse. He was a genuinely religious man and is very likely to have sought understanding in the Bible for his problems. Nevertheless, the spur of the love affair undoubtedly drove him on – although we shouldn’t assume that he immediately intended to marry Anne.

It was certainly not unusual for Popes to grant powerful Kings ways out of undesirable marriages, and had circumstances in Europe been different, Clement VII might well have looked favourably on Henry’s request. Unfortunately for Henry, the rising tide of Lutheranism challenging Papal authority made the Pope less likely to rule that his predecessor had acted outside his powers in granting the dispensation.

This reluctance was compounded by the fact that Rome had been comprehensively sacked in 1527 by the troops of the Emperor Charles, who now dominated Italy. Charles was disinclined to see his aunt cast off and his cousin Mary disinherited – he may have declined to marry the child but that did not mean that a cousin who was likely to be Queen of England wasn’t a useful branch in his family tree.

Clement agreed to a trial of the marriage in England, presided over by Cardinal Wolsey (who Katherine almost certainly wrongly, blamed for stirring up the matter in the first place) and Cardinal Campeggio.

The trial took place at Blackfriars in 1529 and Katharine’s speech to Henry, against all legal etiquette, is one of the most famous in Tudor history. In it, she declared that her marriage was valid as her previous marriage had not been consummated, she firmly denied that the loss of the many children that she and Henry had had was her fault, she reiterated her faithful and loving service as his wife and finally, declared that she would not accept the jurisdiction of anyone less than the Pope himself. She then sailed majestically out of the court, refusing orders to return. No doubt the King was uneasily aware of the cheers with which their beloved Queen was greeted by the waiting crowd.

Katharine and Henry’s marriage limped along in public for another two years, during which time she continued to be treated as Queen. Eventually in 1531, she was banished from court and forbidden from seeing either Henry or her daughter again. Over the next two years Henry determined to take matters into his own hands and in January 1533 he married Anne Boleyn in secret.

In April 1533 the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, convened another court at Dunstable at which he declared that Katharine’s marriage had been null and void from the beginning. In 1534 the Acts of Supremacy and Succession made it a criminal offence to refer to Katharine as Queen: she was demoted to her previous rank of Princess Dowager of Wales.

Katharine absolutely rejected the validity of Cranmer’s annulment of Henry’s marriage to Anne. She continued to write to the Pope requesting him to confirm her marriage and she refused to communicate in any way with anyone who did not address her as Queen.

She was moved further away from London, eventually to Kimbolton Castle, under the guardianship of Sir Edmund Bedingfield. In January 1536, when it became apparent that she was dying, Henry permitted a last visit from Eustace Chapuys, the Emperor’s ambassador – whether as a gesture of compassion or to demonstrate to the Emperor that his aunt was not being ill-treated must be a matter of conjecture. He certainly would not permit their daughter, Mary, to visit her mother. After Chapuys’ departure, Maria de Salinas, Lady Willoughby, who had come from Spain with Katharine thirty-six years before, lied her way into see her former mistress, who died on 7th January 1536.

There is a letter which purports to have been written by Katharine on her deathbed. Its genuineness has been questioned but the whole tone of it and its last line would certainly seem to reflect Katharine’s life and beliefs. She requests her husband to pay her servants, to love their daughter and to take care of his soul. It ends with the words ‘ lastly I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things .’

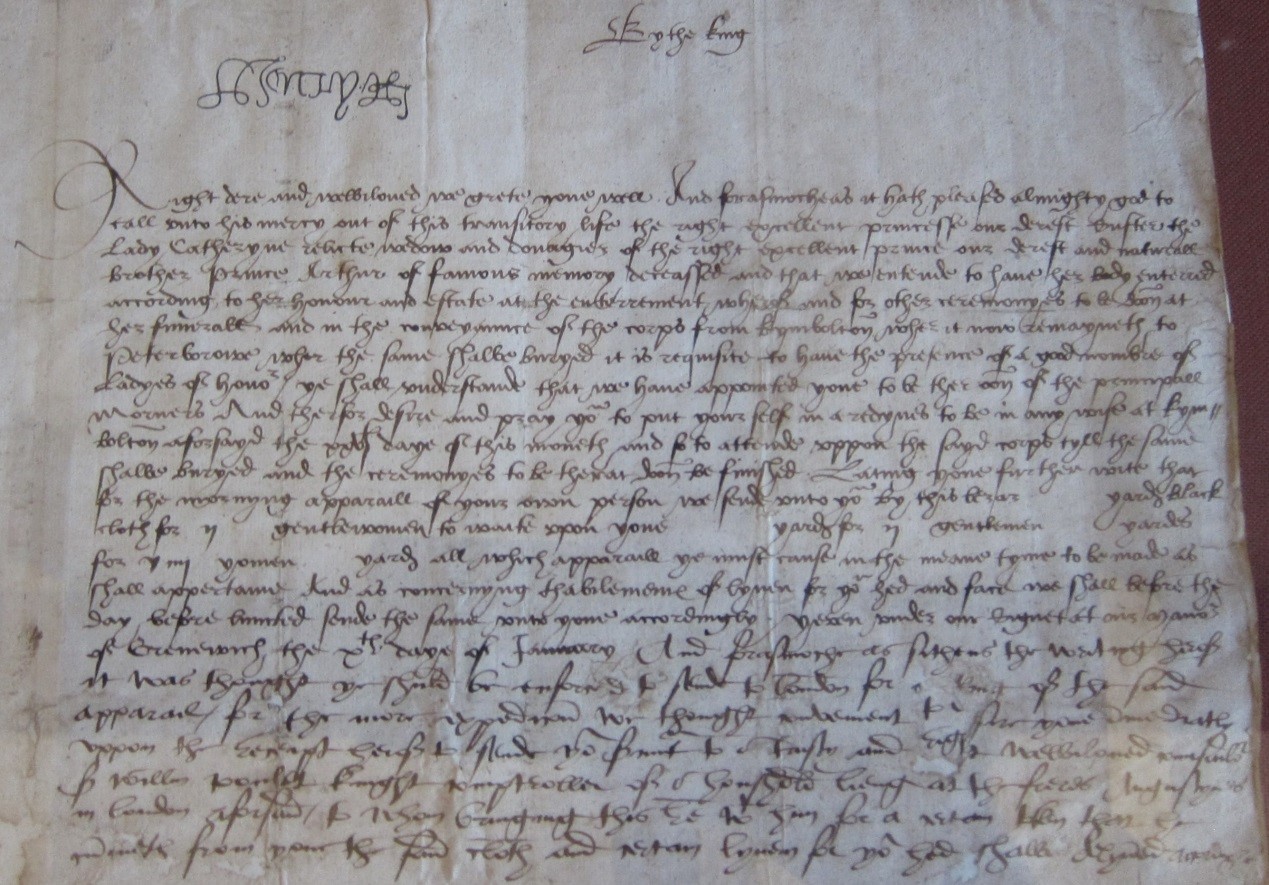

Katharine was buried honourably, in Peterborough Abbey, although in a funeral suitable for a Princess Dowager of Wales, rather than a Queen. The chief mourner was Lady Eleanor Brandon, Henry VIII’s niece, accompanied by other ladies, including Lady Bedingfield who received instructions from the King as to her role.

Katharine’s monument, renewed in the 19 th century, is still honoured, and the arms of England and Spain were re-hung in the 20 th century on the orders of Queen Mary of Teck, wife of King George V.

Katharine of Aragon

Family Tree