Katharine of Aragon: Alhambra to the Fens

In Katharine’s youth, she travelled extensively in Spain, but once in England most of her life was lived in the castles and palaces of the south-east, until she was banished from court in 1531.

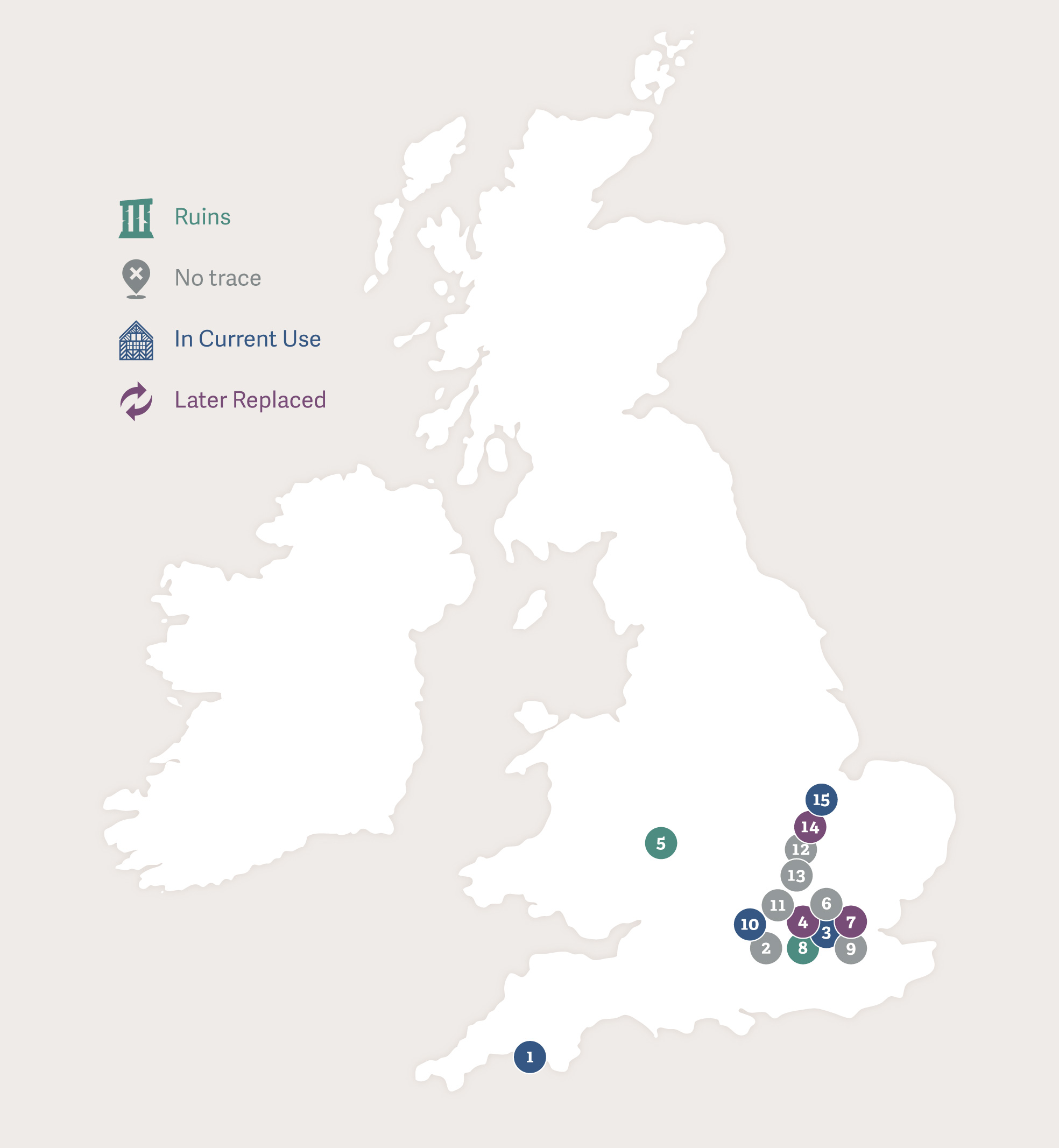

The numbers against the places correspond to those on the map here and at the end of this article.

Katherine was born not far from Madrid in the centre of modern day Spain in the town of Alcalá de Henares. Much of her childhood was spent travelling up and down the country as her parents sought to establish their authority and to conquer the kingdom of Granada – the last remnants of the Moorish conquest of A.D. 711.

In 1499, the royal family settled in the Alhambra, the fairy-tale palace which is now a World Heritage site – it was a scene of beauty and sophistication that even the most modern and harmonious of the Tudor palaces built in Katharine’s lifetime could never match.

In the autumn of 1501, Katharine set sail for England, with the intention of landing in Southampton. Storms blew her little fleet off course and the Princess arrived in Plymouth (1) on 8 th October. Then, as now Plymouth, was a naval town. Katharine showed an interest in ships and the navy throughout her time as Henry’s queen, so Plymouth’s superb harbour was probably a welcome sight, not just as an escape from a terrible crossing. Her first action after disembarking was to go to the nearest church to give God thanks for her safe arrival.

The Princess rested in Plymouth for some days before beginning her journey towards London. Progress was slow and it was not until 6th November that she reached the palace of the Bishop of Bath and Wells at Dogmersfield (2), near Odiham in Hampshire. It was there that she first set eyes on her future husband, Arthur, Prince of Wales. Nothing remains of Dogmersfield today, and even its exact location is not certain. Arthur and his father, Henry VII, preceded the Princess to London to ensure that all was ready for her arrival.

Katharine’s journey ended in Southwark, on the south side of the Thames, almost opposite the royal Palace of Westminster. She was the guest of Henry Deane, Archbishop of Canterbury, in his great Palace of Lambeth (3) which is still the official residence of the Archbishop today.

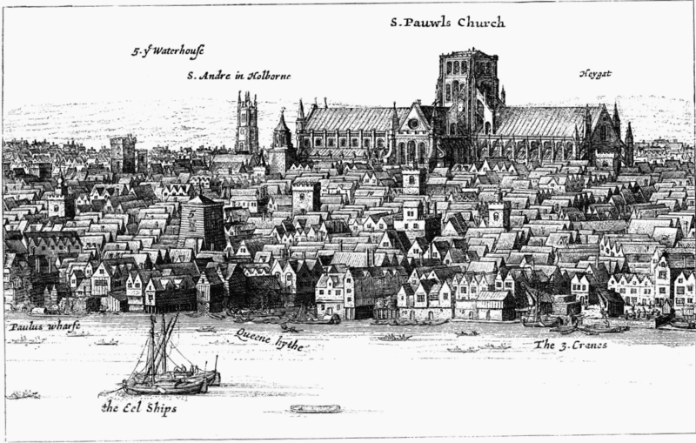

On 14th November 1501, Katharine and Arthur were married in St Paul’s Cathedral (4). The day was no doubt selected because it was the Feast of St Erkenwald, the seventh century bishop whose tomb in St Paul’s was a place of pilgrimage. The church that Katharine knew deteriorated in the sixteenth century, St Erkenwald’s shrine was demolished in Edward VI’s reign and the steeple was badly damaged by lightening in 1561. The whole cathedral was burnt to the ground during the Great Fire of London in 1666. The current replacement, the masterpiece of architect Sir Christopher Wren, was completed in 1708 during the reign of Queen Anne. It was at St Paul’s Cathedral that public thanksgivings or commemorations were held, and it was there that Luther’s works were burnt in 1521. In 1525 Henry and Katharine went in procession to St Paul’s to celebrate the capture of François I, by the Emperor Charles, at the Battle of Pavia.

Not long after they were, married the decision was taken that Katharine and Arthur would travel to the Marches of Wales where Arthur had been living on and off for several years. Arthur’s role was to preside over the Council of Wales and the Marches as a preparation for kingship. He had a number of houses in the area but Ludlow Castle (5) was his main seat and it was there that he and Katharine went early in the New Year of 1502. The winter and spring of 1502 appear to have been wetter and colder than usual and it’s not difficult to imagine that Katharine heartily wished herself in sunny Spain.

Whether she was happy in her married life we can never know. Her later assertions that she and Arthur did not consummate their marriage and the implication she gave that it was on account of his youth suggest that the young couple were hardly Romeo and Juliet. Nevertheless her husband’s death must have been a blow to her, if only for the reason that she had been brought up since she was four years old to believe that was her destiny to be Queen of England. Returning home as a widow at the age of 16 might have felt like failure.

An initial request by Katharine’s mother, Queen Isabella, for her daughter to return home was quickly followed up by beginning of negotiations for Katharine to remain in England to marry Arthur’s younger brother, Henry, now heir to the throne. Katharine returned to London and spent the next seven years either in rooms at the court – usually Richmond or Windsor - or at Durham House (6) in the Strand.

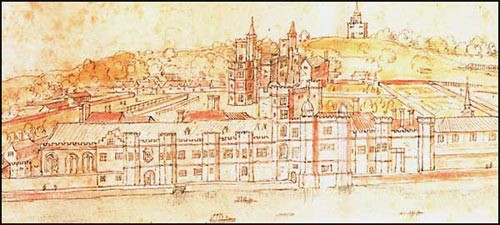

Durham House had been built in the 1220s and was on the westernmost edge of the city of London, bordering on Westminster. It could be accessed from the river, which was convenient as the majority of travel by the court in and around the palaces was by boat. We know that Katharine used this means of transport as there is an entry in the Privy Purse expenses of her mother-in-law, Queen Elizabeth of York, for conveying the Princess in Elizabeth’s own barge pulled by 16 oarsmen. The trip was from Durham House to Westminster Palace and back again on 6 November 1502. The oarsmen received 4d each, and the master 16d.

Later, Henry preferred to minimise Katharine’s expenses by requiring her to live at court although she saw little of her supposed fiancé, Prince Henry. In the late 1520s and early 1530s, Durham House was lived in by Sir Thomas Boleyn and his daughter Anne. Perhaps Anne thought of Katharine’s long wait for marriage to Henry as she herself paced the gardens, running down to the Thames.

The limbo in which Katharine existed following her widowhood became a paradise in 1509 when Henry VII died and the new king, Henry VIII, to whom she had been betrothed for six years immediately claimed as his wife. The couple married on 11 th June 1509 at the Palace of Placentia, Greenwich. (6) This palace had originally been built by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester in the early 1400s, and was a great favourite with both Katharine and Henry. It was here that their daughter was born in February 1516.

In the early years of Henry and Katharine’s marriage, they spent a good deal of time at Richmond Palace (7), which had been comprehensively rebuilt by Henry VII following the destruction by fire of the old Palace of Sheen. It was at Richmond that Katharine and Henry’s son Henry, Duke of Cornwall was born and lived for eight short weeks. Little remains of Richmond now, other the red brick ruins of Henry VII’s gatehouse (with his arms recently restored) and a courtyard of largely 18 th and 19th century houses in Tudor style. It was at Richmond that the Tudor age finally closed when Elizabeth I, daughter of Katharine’s rival, Anne Boleyn, died there in 1603. Although the Jacobean court of King James, Queen Anne and Prince Henry of Wales frequently visited, as time passed the Palace fell into disuse and much was sold off under the Commonwealth.

During the happy years of their marriage, Katharine and Henry had many interests in common, including a taste for chivalry and romance. Henry took the quasi-religious status of the Order of the Garter very seriously. He ordered the construction of an oriel window in King Edward IV’s chapel on the north side of the quire in St George’s Chapel, Windsor (8), from which Katharine was able to watch the Garter ceremonies. The window, which has been redecorated with her arms, was the location from which Queen Victoria watched the wedding of her son Edward, Prince of Wales, to Alexandra of Denmark in 1863.

If Katharine’s ghost walks at Windsor she is able to look down and see the tombstone marking the grave of Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour. Henry had originally intended that he and Katharine would be interred in a sumptuous tomb at Westminster Abbey but that was obviously no longer appropriate after Henry had his marriage to Katharine annulled. Although Henry and Katharine were not to be buried together, it was at Windsor that she last saw him in the summer of 1531. The court was in residence when Henry rode out hunting one day, accompanied by Anne Boleyn. He gave orders that Katharine was to leave before he returned.

St George’s Chapel is open to the public today and more information can be found about access on the Windsor Castle website.

In 1526, Henry began to question the validity of his marriage to Katharine. After a good deal of delay by the Pope amidst an ever-changing European political scene, a court was opened, presided over by Cardinals Wolsey and Campeggio to try the case. The hearing took place at the Priory of Blackfriars (9) in London. The Priory, which was a Dominican house, was an important landmark in London and was frequently used for meetings of Parliament and the King’s Council. It was a popular site for courtiers to be interred, amongst them Sir Thomas Parr in 1517 and his wife Maud Green, Lady Parr, in 1531. Lady Parr had been one of Katharine’s ladies in waiting and her daughter, Katherine Parr, married Henry in 1543.

It was during the court hearing that Katharine staged the scene for which she will be forever remembered. Refusing to recognise the validity of the court, she crossed from her seat and knelt before her husband proclaiming the validity of their marriage, her faithfulness as a wife and the lack of blame that could be imputed to her for the loss of their children. Despite this dramatic plea, Henry did not relent.

Blackfriars Priory was dissolved in 1538 and on 12th March 1550 at least part of it was granted to Sir Thomas Cawarden, who was Edward VI’s Master of the Revels. Further associations with the theatre continued – Blackfriars Theatre was owned by Shakespeare and his partners in The Lord Chamberlain’s Men. When a dispute with the landlord arose, they picked up the building to move it from Blackfriars to Southwark, where it became known as the Globe Theatre. During Elizabeth’s reign, Sir William Cecil had a property at Blackfriars and a number of his letters are dated from there.

Like many of the religious houses that once dotted London, Blackfriars is remembered today in a number of place names – most obviously the Blackfriars Bridge and Blackfriars station. The location of these marks the south east corner of the original Priory lands.

When Katharine was ordered to leave Windsor in 1531, she was sent to a house called The More (11) in Hertfordshire, which had been owned by Cardinal Wolsey in his capacity as Abbot of St Albans. Wolsey spent considerable sums of money on this, as well as on his other houses, improving the lodgings and laying out gardens. The house was sufficiently impressive for it to be the location of the signing of the Treaty of The More between England and France in August 1525 and it was compared very favourably with Hampton Court.

Thus, when Katharine was sent there in 1531 it was not intended that her dignity and status should be seriously diminished. After Katharine had left in 1532, Henry frequently used the property and spent considerable sums on both buildings and gardens, creating separate King’s and Queen’s lodgings. It was also used by Edward VI but was not favoured by either Mary or Elizabeth. It appears that the property suffered from subsidence and by the time it was granted in 1576 to the Earl of Bedford, it was in some decay, and considered ruinous 20 years later. The Earl built himself a new house known as Moor Park which is still extant. This is the Moor Park famous for the apricots that readers of Jane Austen will remember were boasted of by Mrs Norris in Mansfield Park. The site of the Palace that Katharine would have known was extensively excavated in the early 1950s.

When Henry ordered that Katharine should leave The More, she was sent to Ampthill (12). Ampthill today is a busy town in Bedfordshire - the old high Street is recognisably mediaeval in origin. Ampthill Castle was originally been built by Sir John Cornwall, husband of Elizabeth of Lancaster and thus brother-in-law to King Henry IV. It came into Henry VIII’s possession in 1524.

The Castle, where Katharine was lodged, was located in what is today Ampthill Park to the north of the town. What is believed to be its location is marked by a monument called the ‘ Katharine Cross’, erected in 1770s. The wording originally inscribed on the cross was said to be by Horace Walpole:

In days of old here Ampthill's towers were seen,

The mournful refuge of an injured Queen;

Here flowed her pure but unavailing tears,

Here blinded zeal sustain'd her sinking years.

Yet Freedom hence her radiant banner wav'd,

And Love aveng'd a realm by priests enslav'd;

From Catherine's wrongs a nation's bliss was spread,

And Luther's light from Henry's lawless bed.

Katharine’s sojourn at Ampthill was not long, but whilst she was resident in the county of Bedfordshire, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer opened a court a Dunstable Priory (12) in May 1533, at which her marriage was declared invalid.

The parish Church of St Peter at Dunstable was begun in the 1130s and complete some twenty years later. Early in the next century, a house of Augustinian friars was attached to it. The friary was dissolved in 1547, but the church remained to serve the parish and is still standing.

Katharine was no longer considered by Henry to be his Queen, and with the legal justification given by Cranmer for demoting her status, she could now be treated more harshly. In 1533 she was sent to Buckden (13) in Cambridgeshire. Today there is almost a direct road between Ampthill and Buckden, the A660. This probably follows the route that Katharine would have taken, travelling north-east, skirting Bedford and crossing the modern A1 to join the old Great North Road which runs directly through the town of Buckden. It is a pleasant and easy drive today, more interesting than the A1.

Buckden Palace was in the possession of the Bishops of Lincoln and was of sufficient stature to have been used from time to time by Henry’s grandmother, Lady Margaret Beaufort. Sufficient elements of the late 15th century palace remain to give a strong impression of the building in which Katharine passed many unhappy months. It is a pleasant enough place in spring or summer but in winter, with the wind whistling over the flat fields of Cambridgeshire it must have been bitterly cold. It was, however, on the main road, and not isolated in the fens, which was the situation of Somersham castle, to which Katharine was ordered to move in 1534. She adamantly refused to go somewhere so unhealthy, locking herself in her room at Buckden, probably in the tower that can still be seen. Henry’s commission did not dare to take her by force.

Having refused to move to Somersham, the decision was taken that Katharine must go to Kimbolton Castle (14). Kimbolton is situated about nine miles back towards Bedford on the A660. It is another charming English town with a mixture of 18 th and 19th century façades on properties that are probably several hundred years older. Kimbolton Castle itself is now a vast 18 th century mansion, housing a school. Inside there are traces of the buildings as they would have been in Katharine’s time, but they are not always accessible to the public.

Katharine died at Kimbolton on 7th January 1536. On the 27 th of the month her body left Kimbolton to make its final journey, stopping overnight at Sawtry before arriving at Peterborough Abbey (15), as it then was, on 29th January and being interred the same day.

Visitors to Peterborough Cathedral today will see a black marble monument which was erected in the 19 th century, paid for by subscriptions from ladies shared Katharine’s Christian name in its many varieties of spelling. The words 'Katherine the Queen' are affixed to the grill above the monument in recognition of Katherine’s much loved memory.

Listen to our interview with Renaissance English History Podcast on Katharine of Aragon here

The map below shows the location of the places associated with Katharine of Aragon discussed in this article.