Mary I

Beloved Daughter (1516 - 1531)

Mary was her parents' only child to survive more than a few weeks, and almost as soon as she was born, her father, Henry VIII, sought to use her, as was customary, by promising her in marriage to France, then to the Empire.

As the years passed and no more living children were born to Henry and Katharine of Aragon, Mary's importance as a possible inheritor of the Crown of England increased. By 1525, with no legitimate male heir, Henry was torn between naming Mary, or her illegitimate half-brother, Henry Fitzroy, as his successor.

Mary was sent to Ludlow, to preside over the Council in Wales, although she was never formally invested as Princess of Wales. Whilst there, she continued her Humanist education - languages, history, philosophy and the courtly accomplishments.

In 1528, she was recalled from Wales as Henry VIII came up with a much better solution – in his own mind at least – to the problem of an heir. He sought an annulment of his marriage to Katharine of Aragon, in order to marry Anne Boleyn, certain she would provide a male heir.

Exile (1531 - 1537)

Over the following years, as the annulment suit dragged on, Mary's position remained as before, although her household was reduced, and, she was permanently separated from her mother in 1531.

On the birth of Anne's daughter, Elizabeth, in September 1533, Mary's status was degraded from Princess to merely 'the Lady Mary, the King's daughter', her household was disbanded and she was sent to join the new baby at Hatfield, protesting bitterly that she was still her father's only legitimate child and heir.

Whilst at Hatfield, she was subjected to a continual stream of petty bullying and humiliation, but although her health suffered, and never truly recovered, she refused to give in.

On Anne's execution, Mary obviously hoped to be reconciled with her father, but there was no let-up in the pressure placed on her to accept both the Royal Supremacy over the Church and that her parents' marriage had been invalid.

Eventually, aged twenty, browbeaten and terrified, she gave in, and accepted both points.

Back in Favour (1537 - 1547)

Henry was delighted to restore his daughter to favour.

She was brought to court where she developed a warm relationship with Queen Jane Seymour, standing godmother to Prince Edward, and acting as chief mourner at Jane's funeral in October 1537. Despite her rejection of Elizabeth's legitimacy, she was kind-hearted enough to plead for the little girl, now sadly neglected.

Mary was also on good terms with Anne of Cleves, although Katheryn Howard, some five years younger than her, complained of her step-daughter's lack of respect. Mary mended her ways, and was forgiven. After Katheryn's death, Mary spent much of her time at court, acting as her father's hostess.

During Katherine Parr's tenure as Queen, Mary lived largely at Court where ambassadors remarked on their close friendship, although Katherine's clandestine marriage to Thomas Seymour within weeks of Henry VIII's death was looked on by Mary with a chilly eye.

Religious Differences (1547 - 1553)

Throughout Henry's reign, after accepting the Royal Supremacy, Mary conformed to every statute on religion. Matters changed, however, when Henry died, to be replaced by Edward, and his Protestant leaning Protector.

Mary refused to accept the 1549 Prayer Book. For some time she was permitted to continue to hear the Mass, under protection from her cousin, the Emperor, but her flagrant abuse of what was intended as a personal privilege (inviting others to hear Mass in her Chapel) led to a showdown with the Council. She refused to hear the new service, and they refused to allow her to continue with the old.

As Edward's Government became more hard line under the leadership of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, Mary considered escaping to the Low Countries but changed her mind at the last minute, after the Emperor had already sent a ship for her.

Fighting for the Crown 1553

In early July 1553, Mary received word that her brother was ill and summoning her to attend him. En route, she learnt that Edward was, in fact, already dead and that their cousin, Lady Jane Grey, had been proclaimed Queen.

Mary galloped for the stronghold of Framlingham in Suffolk, sending letters to the Council and to major cities, declaring her rights and demanding that she be proclaimed Queen immediately. Before long she had a sizeable army. A Lincolnshire man wrote to the Council:

'Her grace should have her right, or else there would be the bloodiest day…that ever was in England.'

Back in the capital, Jane had been persuaded that it was her duty to accept the Crown to protect the Protestant faith. The Council, hearing that Mary was planning to resist being deprived of her rights, decided to send an army to enforce Jane's accession. But no-one could be found to lead the troops, except Northumberland.

Almost as soon as Northumberland had departed, the individual lords of the Council sent secret messages to Mary. Soon news came that Northumberland had surrendered and Mary was proclaimed as Queen.

Mary, flanked by her supporters, entered London in triumph, to a tumultuous public welcome. She was joined by her half-sister, Elizabeth, who had done nothing to aid either party.

Northumberland was executed, and Jane, having been found guilty of treason was detained in the Tower whilst Mary contemplated her fate.

Mary’s Policy (1553 - 1554)

Mary had two ambitions: to restore the Catholic religion and to have an heir of her own. Both ambitions were within the realm of the possible as matters stood in 1553, but there were serious obstacles to their easy achievement.

To take the religion first, the majority of the population, other than a small vocal group in London and the south east, was still Catholic. A return to the settlement at the death of Henry VIII - essentially one of Catholic practice, with innovations around an English Bible, and the removal of the Pope as the Head of the Church was achieved in Mary's first Parliament, and reflected the opinions of most people.

The question of Papal Supremacy was more difficult. There was plenty of enthusiasm for the return of the saints' days, the processions, the prayers for the dead and the ritual of the centuries, but there was little appetite for payment of taxes to a foreign power or the reversing of the land distribution that had followed the dissolution of the monasteries. Even committed Catholics in religion had profited greatly from the land grab, and few were willing to put their souls above their purses.

For Mary, Papal Supremacy mattered, because, if the Pope had no spiritual power higher than that of other bishops, he could not have legitimately granted the dispensation for her parents' marriage.

Marriage Plans (1554)

The second item on Mary's agenda, the getting of an heir, was just about practicable had she been in good health, but Mary was not particularly robust and was well over 37 when she became Queen.

There was no shortage of candidates for her hand, and Mary's Councillors and subjects expected her to marry as soon as possible, not just for an heir, but because received wisdom was that women were not suited to being monarchs or in positions of power, although it was enacted in Mary's first Parliament that she had exactly the same authority as a male sovereign.

It was thought that a Queen's husband would be King, for at least as long as she lived. To marry one of her subjects would therefore cause enormous friction as one noble was elevated above the others. To marry a foreign prince risked Mary being taken abroad and England devoured by his country. To remain unmarried was not an option that anyone considered feasible.

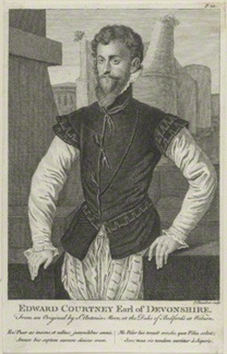

Mary had two marital options at home - her second cousin, Edward Courtenay, her nearest male blood relative of age to marry or Reginald, Cardinal Pole, great-nephew of Edward IV. But Courtenay had spent so much time in the Tower that he lacked the maturity and experience that Mary needed in a husband and Pole, whilst not an ordained priest, was a Cardinal.

Wyatt’s Rebellion (1554)

Mary's heart was set on a marriage with a foreign prince, partly for reasons of prestige and to reinvigorate England's position as a member of the wider Catholic Christendom. Her preference fell on Philip, twenty-seven years old and the son of her cousin, Emperor Charles V.

Mary was determined to have her way, despite misgivings among her Councillors – although none them was so averse to the match that he couldn't be bought with a pension. Philip was heir to Spain and the Low Countries.The marriage treaty provided that any heir Mary bore would inherit England and the Low Countries - England's biggest trading partner. It was agreed that Mary retained sovereign right, but that he would be King, and they would have the regal title of Philip and Mary, Kings of England, Spain, France etc etc through a vast list of Princedoms, Archduchies and Lordships.

It was also confirmed that England would not be expected to involve itself in Philip's Italian Wars, nor could Philip make any political appointment, whilst any power he held would be relinquished on her death. It was expected, however, that he would influence Mary, and, to an extent, he did.

As soon as the proposed marriage became public knowledge, it stirred discontent. Fear of foreigners was rife, and, amongst a vocal minority of Protestant gentry, there was an open rebellion, led by Sir Thomas Wyatt. Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, father of Lady Jane Grey, was also involved. Wyatt claimed that his aim was to prevent the match with Philip, but most people believed it was to replace Mary with either Jane Grey or Elizabeth.

Mary, displaying her usual qualities of courage, determination and decisiveness in dangerous situations, reacted immediately. She called out her troops and, refusing to flee in the face of a rebel army heading into London, rode to the Guildhall and made an impassioned speech, defending her rights to the Crown and her determination to undertake the marriage only if it were of benefit to her people. The rebels were defeated and Mary was safe.

Unfortunately, Jane Grey was not. Persuaded that as long as Jane lived, there would be uprisings in her favour, the sentence of execution was carried out. Mary was clear that, if Jane accepted the Catholic faith she would be spared but Jane, just seventeen, would not renounce her faith.

Jane dispatched, attention was diverted to Elizabeth, who as before, had neither given any indication of support for the rebels nor any show of loyalty to Mary. There was evidence that potentially incriminated her so she was sent to the Tower of London whilst it was examined.

Mary, although she had reluctantly accepted that Jane's death was necessary, was adamant that her half-sister could not be convicted without solid proof. None was forthcoming, so, eventually, Elizabeth was sent from the Tower to house arrest in Oxfordshire.

Meanwhile, Mary had advanced towards her objectives. Parliament, reassured that none of the monasteries' lands would need to be returned, repealed all of the religious legislation of the preceding twenty years and submitted the English Church once more to the supremacy of Rome and Philip arrived. He and Mary were married at Winchester Cathedral on 25th July 1554.

All appeared to be going swimmingly. Mary believed that she had fallen pregnant and she retired to Hampton Court in spring of 1555 for the confinement. Tragically, there was no pregnancy. The diagnosis is unsure - phantom pregnancy, ovarian cancer or some other disorder are all possible.

Meanwhile, the campaign to restore England to the Catholic religion was unfolding. The heresy laws, relaxed in Edward's reign, were re-enacted. Death by burning was prescribed for unrepentant heretics.

This is one of the most difficult aspects of Mary's reign to understand in the modern mind. In the sixteenth century, burning for heresy was considered an appropriate response as heretics endangered the souls of others, which was a terrible crime. Hanging, drawing, quartering, branding and having ears and hands chopped off were also normal punishments.

The concept of freedom of conscience was almost unknown. Catholic and Protestant States all over Europe routinely slaughtered adherents of the wrong faith. Heretics and atheists had burnt under Henry VIII, under Edward VI, and would continue to be cast into the flames in the reigns of Elizabeth and James I.

What is different in Mary's reign is, first, the scale of burnings (although they were a good deal less frequent than on Europe). In the past, heresy had been unusual and confined to a few people, but now the Reformation had spread to the extent that there were vast numbers of people who believed differently.

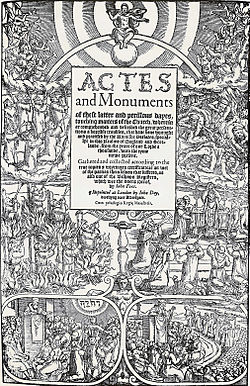

The second difference is political. Much of our knowledge of the persecutions has come from the radical Protestant, John Foxe's, Book of Acts and Monuments. This work became the most influential work in English after the Bible. It had a place on every Englishman's bookshelf and imbued a horror of popery that can still be recognised today.

The victims of the fires were drawn from the radical and vociferous proponents of their faith - people who kept quiet were not sought out. Mary's Government had a policy of encouraging radical Protestants to leave the country, and there was a steady stream of high-ranking exiles who took refuge in Geneva. The unhappy effect of this was that members of the court who conformed were not punished whilst the poor and defenceless were.

The most notable deaths were of the three bishops, Latimer, Ridley and Hooper, and, highest ranking of all, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who had pronounced Mary's parents' marriage invalid. In a rare example of personal revenge, the death of Cranmer was as certainly Mary's doing as if she had killed him with her own hand, when he was not pardoned after recanting Protestantism, which was the usual practice.

Despite most depictions of her, Mary's own religion was not the unregenerate superstition that Humanists derided in the 1520s. The programme that Pole, who had been installed as Archbishop of Canterbury, and she planned to implement addressed many of the concerns of the early reformers. Priests were to be of good repute and a new translation of the Bible into English was planned.

Many hard-line Catholics considered Cardinal Pole to be a heretic himself, as he was unsure in his own mind on the question of "Justification by Faith Alone" that was the early point of divergence between those who sought to reform the Catholic Church, and those who considered its teachings to be wrong.

Where neither Mary nor Pole could tolerate any leanings towards Protestantism, was in the rejection of the doctrine of transubstantiation. This, effectively, became the test of whether a so-called heretic would burn or not.

Disappointment

The burnings continued, Philip left England, to Mary's distress, and several years of appalling harvests compounded economic problems. The extravagance of her father's reign and the poor husbandry of Edward's protectors had left the financial affairs of the crown in a very parlous state. New coinage was issued to try to get on top of inflation, and a good deal of retrenchment and even penny pinching began.

Unfortunately, one of the areas were expenditure was slashed was in the defences of Calais, the last English toehold in France. The Governor warned of decaying defences, but no money was available for repairs.

In 1557, Philip returned to England. In another round of the interminable Italian wars he was planning a campaign in France, and hoped for English support. Bizarrely, this war led to Philip being in direct conflict with the Pope, who, in retaliation, tried to recall Cardinal Pole to Rome to face heresy charges. Mary might have believed in Papal Supremacy, but she would no more let the Pope dictate to her than any of her predecessors. She categorically refused to let Pole leave the country and be replaced with a Papal nominee.

The Loss of Calais (1558)

Despite the misgivings of the Council, the young nobility were agog to join the King in his expedition. Philip's army achieved a stunning victory at St Quentin but, Philip, always over cautious, failed to follow it up, and whilst he was dithering, a lightening swoop by Henri II recaptured Calais on 7th January, 1558.

Mary, her Government, Parliament and people were appalled, but there was no money or leadership to take it back. She is alleged to have mourned this bitter climax to her reign with the words 'When I am dead and opened, you shall find Calais engraved on my heart'.

The End of an Era

In 1558 after another poor harvest, a severe epidemic of influenza struck England. People died in their thousands and the Queen fell ill. She had made her Will in hope of bearing a child, but, knowing that was now impossible, she added a codicil, not naming Elizabeth, but referring to her heir 'by the Laws and Statutes of the Realm'. She directed that her father's and brother's debts be paid, and left bequests for the new religious houses she created. She also wanted her mother's body to be exhumed and laid to rest with her. None of these wishes was carried out.

At the very end, Mary accepted that Elizabeth must inherit, and sent her the coronation ring. Mary died, aged 42, at St James' Palace. Her funeral oration was preached by John White, Bishop of Winchester who praised her in glowing terms:

“..she used singular mercy towards offenders. She used much pity and compassion towards the poor and oppressed…I verily believe, the poorest creature in all this city feared not God more than she did.”

Elizabeth was not amused and had the bishop thrown into gaol.

Mary left a terrible memory of religious persecution, but she also proved that a woman could rule as well as a man, and that a Queen of England had the same power, majesty and authority as any King. Her tomb is at Westminster Abbey, where she lies interred with Elizabeth under the words (in Latin):

"Partners both in throne and grave, here rest we two sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, in the hope of one resurrection."

Mary I

Family Tree