Tudor: The Family Story

Many histories of the Tudor period start with Henry Tudor, erstwhile Earl of Richmond, springing into life as he lands at Milford in South Wales, ready to capture the Crown. This book begins sixty years before and shows the progress of the Tudors from dispossessed gentry of Wales after the failure of Owain Glyndwr’s attempts to throw off English control, to half-brothers of the king, and finally to the Crown. This was achieved first through the clandestine marriage of Owen Tudor to the widowed Queen, Catherine de Valois, then the marriage of their son, Edmund, into a junior member of the Lancastrian branch of the royal family – Margaret Beaufort.

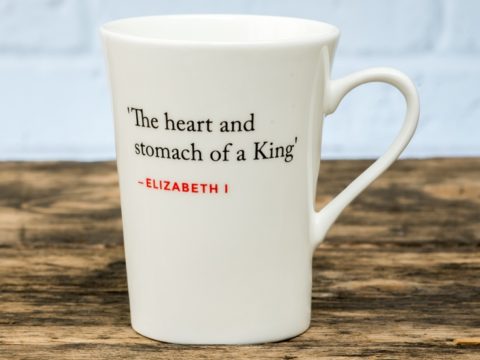

Margaret Beaufort is only the first of the dominating female figures of the Tudor family whom Ms de Lisle shows as using all the weapons available to women when direct power for a female was rare: money, connections, intrigue and the sheer inability of men to contemplate that women might have more complex lives than their outward show of wifely obedience might suggest.

One of the curses of the Tudor family was the tendency of the men to die young: Prince Arthur; Henry Fitzroy; Edward VI; Henry, Earl of Lincoln and Charles, Earl of Lennox all died as young men, and many others in infancy. This left a plethora of female heirs in an era uncomfortable with feminine rule. De Lisle traces some of these young women, the Grey sisters, Lady Margaret Clifford, and Lady Arbella Stuart, through lives often made more dangerous, but never happier, through their proximity to the throne. Ms de Lisle skilfully weaves these characters in and out of the main narrative which follows the five (or six, if Lady Jane Grey is counted) monarchs as they quarrelled amongst themselves, and tried to isolate their heirs.

One of the most interesting facets of Ms de Lisle’s writing, is her challenge to perceptions of history that have been conditioned by propaganda developed by later generations – good examples are the view of Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk and mother of Lady Jane Grey as little better than a child-abuser, which has no basis in contemporary records; the inclination of Mary I to spare Lady Jane, shown here as a clever political ploy, in the wider context of religious turmoil, only foiled by the intriguing of Lady Jane’s father; and the re-evaluation of Lady Margaret Douglas’ relationship with Henry VIII, freed from the ‘spin’ of her enemies.

Necessarily, in a work of this vast scope, not everything can be covered, and there are some tantalising glimpses of other characters whom it would be interesting to learn more about, such as the elusive Lady Eleanor Brandon and her daughter, Lady Margaret Clifford, and Lord Strange and his siblings and children.

Another fascinating character is Lady Margaret Douglas, and Ms de Lisle has written more about her here (see the article labelled History Today).

An elegantly written narrative which gives context to the Tudor century – highly recommended.