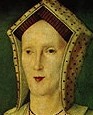

Mary I: Life Story

Chapter 3 : Back in Favour (1536 - 1547)

Henry was overjoyed at Mary’s capitulation, both as confirming his royal authority that had been undermined by her disobedience, and also as a father, fond of his little girl, and hurt by her refusal to accept his will. Mary was given clothes, jewels and money, offered her choice of servants (with the exception of Lady Salisbury) and brought within weeks to Hackney to be reconciled with Henry, whom she hadn’t seen for five long years.

Mary rejoined the court, taking precedence over everyone except the new Queen, Jane Seymour, with whom she soon formed a warm relationship.

There was one more thing for her to do to prove her submission – she must write to her cousin Mary of Hungary, the Regent of the Netherlands (sister of Emperor Charles), confirming her acceptance of her illegitimate status and Henry’s ecclesiastical supremacy. She did as required, but secretly requested absolution from the Pope. Mary was playing a dangerous game – had Henry discovered her duplicity, she might well have ended up in the Tower, or perhaps even on the scaffold.

Fortunately, Henry was satisfied and Mary was treated with affection and honour, although she was not restored to the succession in the act of 1536 which also barred Elizabeth from inheritance. The rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, which began in October of 1536 had, as one of its stated aims, the restoration of Mary to the succession, but despite the participation and execution of Sir John Hussey, who had once been her Lord Steward, Mary was not suspected of any involvement. She spent the Christmas of 1536 at court, and must have witnessed Henry’s treatment of the rebel leader, Robert Aske, as practically a long-lost brother, whilst he awaited the opportunity to destroy him.

In the following spring, it was suggested to Henry that Mary might be declared legitimate so that she could make a marriage of alliance, but, with a pregnant Queen, Henry refused. Mary returned to Hampton Court in the summer of the year to witness the birth of Jane’s son, Edward. On 15th October she stood as god-mother to her half-brother, giving him a golden cup, which he presumably valued once he was older, and the munificent sum of £30 to be shared by his nurse and other attendants.

The rejoicing in Edward’s birth was soon overtaken by sorrow for the death of Queen Jane. Mary was so overcome with grief for her kind step-mother that she was unable to take part in the initial mourning duties, but was sufficiently recovered to act as Chief Mourner, following the Queen’s hearse to Windsor, on a horse draped in black.

Mary was more than twenty years older than the baby, and for the first years of his life was the nearest he had to a mother, visiting him regularly in the nursery palace at Richmond, and making him frequent presents. Despite her earlier rejection of Elizabeth’s legitimacy, she was also kind-hearted enough to plead for the little girl, who was now sadly neglected.

With Henry widowed, and Mary marriageable, the late 1530s were a period of negotiation for marital alliances – she was postulated again as a bride for Henri of Orleans, and also for Dom Luis of Portugal. Unfortunately, neither gentleman was willing to take a bride who was not legitimate and Henry was adamant that she was only his ‘natural’ daughter.

1538 was a difficult year – the ramifications of the Exeter Conspiracy resulted in the deaths of Henry Pole, Lord Montague, who was the son of Mary’s former Governess, Lady Salisbury, as well as her cousin, the Marquess of Exeter, whose wife, Gertrude was a close friend of Mary’s. Sir Nicholas Carew, too, once a friend of Queen Jane, was executed. They had all been supporters of Mary and her mother.

By 1539, Henry was looking for an alliance with which he could counter the unusual and unwelcome rapprochement between François and the Emperor Charles. Encouraged by Cromwell, who had Lutheran leanings, Henry sought an alliance with the Schmalkaldic League, led by the Lutheran Elector of Saxony. The plan was for Henry to marry the Elector’s sister-in-law, Anne of Cleves, and for Mary to marry Anne’s brother, Duke Wilhelm of Cleves. Mary was described as full of beauty, learning and virtue, even though she was only Henry’s illegitimate daughter.

No match with Duke Wilhelm was agreed, but a second suitor actually visited in person – Duke Philip of Bavaria. Mary met him in person, and he seemed eager to marry her – even taking the liberty of kissing her, which gave rise to rumours that a wedding would swiftly follow. Whether Mary could have been persuaded to marry a man who was openly Lutheran is debatable, but, in any event, Henry had no intention of letting any match take place.

Meanwhile, the King himself married Anne of Cleves. Mary was the foremost of the court ladies in all of the celebrations arranged to welcome the new Queen. She maintained a good relationship with her, even after Henry, completely unable to stomach marital life with Anne, whom he found physically unattractive, had the marriage annulled. Fortunately for him, the alliance between France and the Empire soon collapsed, and the need for an alliance with the Lutheran princes had diminished. It was less fortunate for Cromwell, who was executed.

No doubt Henry’s infatuation with one of Anne’s maids-of-honour, Katheryn Howard, also influenced his decision to have the marriage annulled. He and Katheryn were married in July 1540.This was difficult for Mary. Katheryn was at least five years her junior, and was also first cousin to Anne Boleyn. The new Queen felt that her step-daughter was not showing her the respect that was her due. Mary quickly mended her ways, and with the easy generosity that seems to have been a hallmark of Katheryn’s character, her step-daughter was invited to reside permanently at court.

Despite the seemingly happy family atmosphere, Mary had to accept the death of Lady Salisbury in May 1541. The sixty-nine year old countess, niece of Edward IV and Richard III, had been held in the Tower since 1539, and was now executed without trial. Her last words were prayers for Henry, Katheryn, Edward and Mary.

By October of that year, Queen Katheryn was being investigated by Archbishop Cranmer and the Council when it emerged that, prior to her marriage, she had had sexual relationships with both her music master, and a distant relative, Francis Dereham. The investigations revealed that the young Queen had also been indulging in a relationship with a gentleman of Henry’s Privy Chamber, Thomas Culpeper. It was debatable whether Katheryn had actually committed adultery, but if the act had not been committed by the time of her arrest, it was certainly the most likely eventual outcome of her secret meetings with the young man.

Katheryn was executed, and Henry, with no new queen in sight, turned to his elder daughter for a female figurehead for the court. He gave her expensive gifts of jewellery, and had apartments fitted out for her at Hampton Court and Whitehall. Despite this favourable treatment, Mary suffered from intermittent ill-health – stomach problems, palpitations of the heart and fevers being amongst the symptoms.

By 1543, recovered from whatever had ailed her, Mary was again presiding over the court, and, in her train was Katherine Parr, the widowed Lady Latimer. In July of that year, Lady Latimer became Mary’s fourth and final step-mother in a ceremony that Mary attended, together with her half-sister, Elizabeth, and her cousin and friend, Lady Margaret Douglas.

Throughout her period as Queen, Katherine Parr treated Mary honourably and with true friendship. They had many intellectual tastes in common, as well as a shared love of music and fine clothes.

Katherine was of a literary, as well as of an evangelical turn of mind, and patronised the translation into English of Erasmus’ Paraphrases on the Gospels. She persuaded Mary, an accomplished Latinist, to translate the Paraphrase of the Gospel of St John. Ill again, during the autumn of 1544, Mary was unable to complete the work, but it was under her name that it was published with the other translations.

Mary’s warm relationship with her half-brother also thrived. He wrote to Katherine, exhorting her to protect Mary from the wiles of the devil, manifested in the princess’ enjoyment of ‘foreign dances and merriments which do not become a most Christian princess.’ He also wrote to Mary herself, gravely informing her that although he did not write to her often, he loved her most, just as he loved his best clothes most, although he did not wear them all the time. Mary’s relationship with Elizabeth was never so close, although she continued to give the younger girl expensive gifts.

In the Parliamentary session of 1543-44, a new Succession Act was passed, in which Mary was named as successor to Edward, should he have no children, to be followed by Elizabeth, should she herself have no heirs. In an unprecedented step, Parliament also gave Henry the right to appoint any successor to follow his three children.

On 28th January 1547, Henry died. It is unlikely that Mary saw him in his last weeks. She and Queen Katherine had spent Christmas together, at Greenwich, but Henry had remained at Whitehall.

Mary was well provided for by the terms of her father’s will. It confirmed her place in the succession, although on the proviso that she could not marry without the consent of a majority of the members of the Council he had instituted to govern during the minority of Edward. In addition, she received an income of £3,000 and a dowry of £10,000 (not so generous as the £50,000 her grandfather had left for his daughter’s marriage), as well as household plate and goods.

In Europe, there was some question as to whether Edward was the legitimate King. Since he had been born after England’s breach with Rome, there were many Catholics who considered Mary, rather than Edward, as Henry’s legitimate heir. Mary made no challenge to her brother, immediately accepting him as King.

Perhaps in recognition of this, when the new Privy Councillors interpreted Henry’s will in a way that resulted in huge land and money grants for themselves, Mary was included in the bonanza, receiving a landed estate that made her one of the richest magnates in England. Her estates were largely comprised of the Howard lands which had been confiscated from the Duke of Norfolk, now languishing in the Tower, and were concentrated in East Anglia.

Mary was, initially, at least, on good terms with the new Protector, Queen Jane’s brother, Edward, quickly named as Duke of Somerset, and seems to have been the only person in England to have a good word for his wife, Anne Stanhope, whom everyone else considered rude and overbearing.

Sadly, within weeks of Henry’s death, a coolness sprang up between Mary and the Dowager Queen Katherine, when the latter secretly married Sir Thomas Seymour, another brother of Queen Jane. Mary was offended by this apparent disrespect towards her father, and retired to her new house at Kenninghall, in Norfolk. The two were reconciled at some point, although they did not meet again, and Mary sent Katherine encouraging letters during the Dowager Queen’s pregnancy. The resulting baby, Mary Seymour, was named for Mary.

Mary I

Family Tree