Mary I: Images

Mary, like all other princesses, was a bargaining tool in diplomatic negotiations. Her personal appearance, education and accomplishments are commented on in ambassadors’ dispatches from her first public appearance, dressed in cloth-of-gold and a black velvet cap at the age of two, to the end of her life.

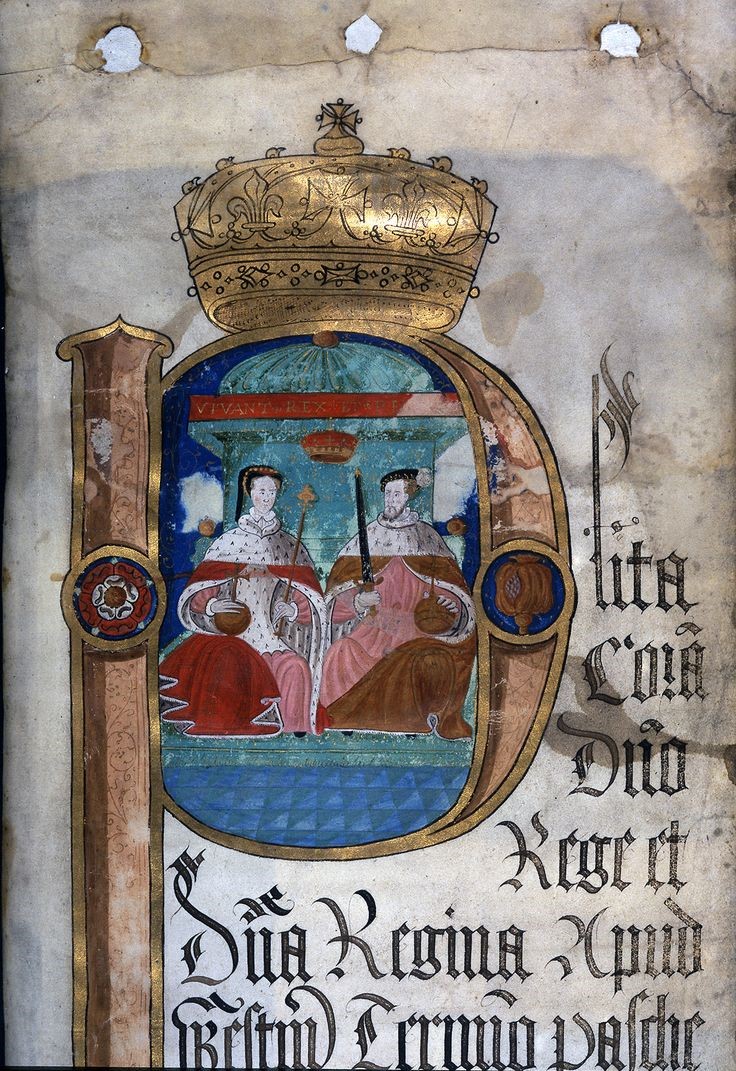

There are also numerous pictorial representations of Mary. Like her grandfather, father and sister, she recognised the power of art to convey a message about kingship and she was careful to be depicted as a monarch in the full panoply of sovereignty in the Coram Rege (King’s Court) Rolls and Exchequer Rolls.

She was also painted during her father’s life-time, and even appeared in art of the following reign, although usually to point a contrast with Elizabeth, in the latter’s favour.

The first physical description of Mary’s person dates to 1522, when she was seven. She was described by the Imperial Ambassador, Lachaulx, as ‘pretty and very tall for her age’. Either Mary had had a growth spurt that was not continued, or Lachaulx did not have much idea about children’s development because every other description of Mary suggests that she was short, including one also from 1522, when there was a report to the Emperor Charles that

‘she promises to become a handsome lady, although it is difficult to form an idea of her beauty, as she is still so small.’

Mary was described by the French ambassadors in 1527 as so slight and small for her age that she could not possibly be married for at least another three years, rather than at the minimum age of twelve. Nevertheless, it was apparent that she had at least one claim to beauty. Following the dancing in which Mary had performed with the court ladies, Henry took off her cap and ‘a profusion of silver tresses, as beautiful as ever seen on human head fell over her shoulders.’ Her hair must have darkened, as blonde hair is wont to do, as all of the later images of her show a red-head.

The first representation that is believed to be of Mary is a miniature dating from around 1525, by the court painter Lucas Horenbout, who painted similar miniatures of her parents, around the same time.

There is a sketch labelled ‘The Lady Mary, after Queen’ by Holbein in the Royal Collection, in which a young woman is shown, wearing the fashionable English hood, with one lappet turned up, associated with Jane Seymour. There is certainly enough similarity between this and the Horenbout image to suggest the same sitter, although in the Holbein sketch she would be about ten years older.

The best known image of Mary as a young woman is that of 1544. The most likely painter is one ‘Master John’, who received £5 in November of that year for painting ‘My Lady’s Grace in a table’, table being the word for a painting. Master John is also credited with the painting of Katherine Parr, dating from the same period. Both are now at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

The final known picture of Mary during her father’s reign, is her figure in the famous ‘ Family of Henry VIII’ dynastic painting at Hampton Court. Mary is the taller of the two princesses, shown on Henry’s right, but carefully distanced from the family group in the centre, depicting Henry, Prince Edward and Jane Seymour (although Jane was, of course, dead by the time of the work.)

So far as is known, there are no portraits of Mary dating from the years of her brother’s reign, although the portrait by an unnamed English painter to the right may be from that period.

Looking at her jewellery in this portrait, it is likely to date from before 1554, as she is not wearing her famous pearl, received from Philip – more on that here. It is probably not much earlier, however, as she is wearing a very similar headdress to that shown in the two by the Fleming, Hans Eworth, dated 1554, one of which is shown at the beginning of this feature in which she is again sumptuously dressed in dark red or burgundy. There is second version of this likeness, currently held by the Society of Antiquaries in which she is dressed in a more vivid shade of red with furred sleeves.

Mary preferred French fashions in clothes, which the Spanish

considered to be gaudy and over-decorated, one going so far as to say

‘The Queen is not at all beautiful: small, and rather flabby than fat, she is of white complexion and fair and has no eyebrows. She is a perfect saint and dresses badly. All the women here wear petticoats of coloured cloth without admixture of silk, and above come coloured robes of damask, satin or velvet, very badly cut.‘

This disapproval of her dress sense may have led Mary to adopt other styles – in the painting below, probably by Eworth, she is in an Italian style – the closed gown with fitted sleeves that became fashionable in the late 1550s.

Mary, like other monarchs, was depicted undertaking her public duties – in the Court Rolls, the Exchequer Rolls, and of course, on the coinage.

Mary is also shown in a manuscript illustration, curing sufferers of a disease known as the ‘King’s Evil’, now called scrofula in a ceremony that pertained to royalty for centuries, it being believed that the touch of a monarch was the touch of God’s Anointed and had healing properties.The last monarch to do this was Queen Anne (d. 1715). Mary took this type of activity very seriously and also left funds for the Savoy Hospital, founded by Henry VII, in her will.

Once Mary married, she is generally depicted with her husband.There are two portrait renderings of Mary with her Philip. The first, dismal from the point of view of artistic merit, shows her seated, and him standing, with an impossibly small dog at her feet. If it were painted from life, it would date from 1554-555, or summer 1557. It has been attributed to Eworth, but it seems hard to believe he could have produced something so lacking in perspective.

Coinage was also struck in their joint names, and they had a fabulously complex seal, which listed their joint titles at length.

From the time of their marriage, Philip and Mary are depicted together in the Coram Rege Rolls:

There is another portrait of Mary that shows her alone. It was by the great Netherlandish artist, Anthonis Mor, who was court painter to Philip. Whilst it has been tentatively dated as 1554, the Queen looks so much older than she does in the portraits by Eworth of that year, that it seems more likely to depict her towards the end of her life.

The final near-contemporary portraits of Mary were made during Elizabeth’s reign. Philip and Mary are depicted as leading Mars, the God of war by the hand, whilst Elizabeth is accompanied by images of peace and plenty. This picture, ' An Allegory of the Tudor Succession', possibly by Lucas de Heere, is inscribed as from Elizabeth herself to Walsingham. It cleverly harks back to the Henry VIII Succession painting above and reinforces Elizabeth’s depictions of herself as Gloriana, compared with Mary as a bringer of war and discord.

This article is part of a Profile on Mary I available in paperback and kindle format from Amazon.