Mary I: Significant Places

Mary lived her life largely in the south and east of England, with the exception of the three years spent in the Welsh Marches where, although a child, she presided over the Council of Wales, as de facto, although not de jure, Princess of Wales.

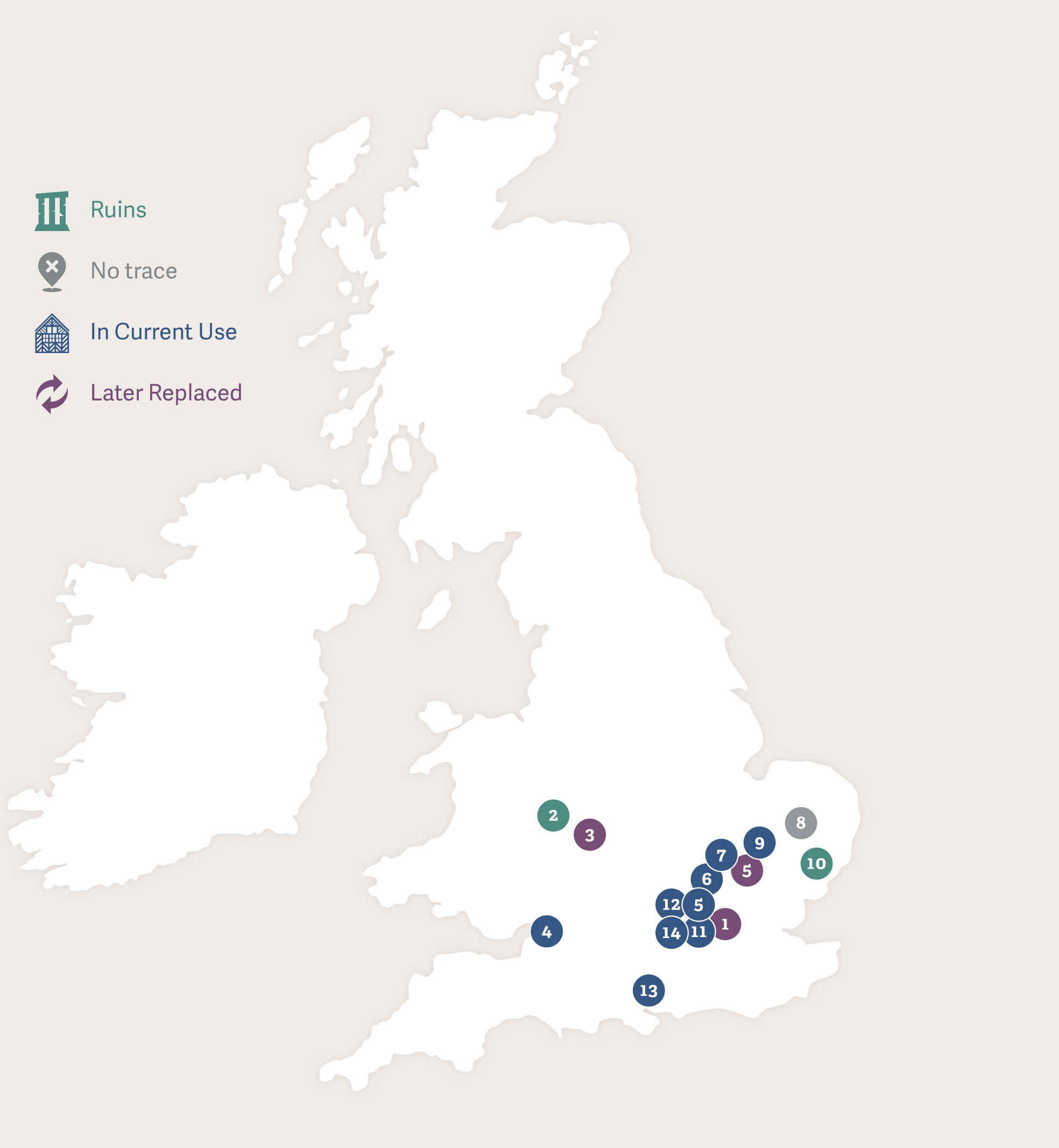

The numbers against the places correspond to those on the map here and at the end of this article.

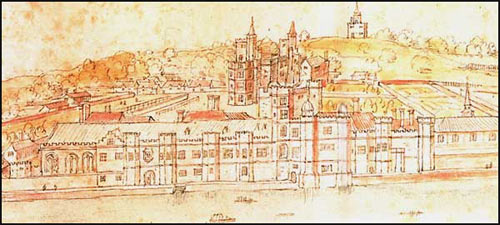

Mary was born at the Palace of Placentia, in Greenwich (1). The palace had originally been built by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, brother of Henry V in 1443: forfeit to the Crown when the Duke died, the palace proved popular with all subsequent monarchs. Mary was christened in the Church of the Observant Friars, next to the palace. Greenwich, as it was generally known, continued to be used by the Tudor monarchs, and also by James VI & I and Charles I. It was demolished on the Restoration of Charles II, and the Royal Naval College built on the site.

During her childhood, Mary travelled around the palaces and royal manors and castles that surrounded London, sometimes with her parents, sometimes with just her own attendants. In 1525, aged nine, she was sent to Ludlow (2), in the Marches of Wales, to preside over the Council of Wales and the Marches. Ludlow had been part of the Mortimer inheritance of Richard, Duke of York, and was subsumed into the Crown when Edward IV became King. Although Mary was not formally invested as Princess of Wales, her regime there was similar to that of her great-uncle, Edward V, and her father’s older brother, Prince Arthur.

Mary and her Council remained based at Ludlow for the following three years, with visits to other properties in the region, notably Tickenhill (sometimes referred to as Bewdley or Beaulieu after the town near Kidderminster in which it was situated). It was at Tickenhill (3) that Mary’s uncle, Arthur, had been married by proxy to her mother, Katharine of Aragon, in 1499. Like Ludlow, Tickenhill was part of the lands of the Mortimers and was enhanced and extended by Edward IV. It consisted of a timber palace with a great hall of at least 100 feet in length, outhouses, a chapel, gardens and a gatehouse. It was replaced in the eighteenth century by the privately owned manor house which still stands.

Another of the great houses Mary occupied during her sojourn in Wales was the castle of Thornbury (4). Thornbury was a very modern building in the 1520s. Construction had begun in 1511 under Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham. Visiting Thornbury must have been a bitter pill for Mary’s Governess, Lady Salisbury, whose daughter, Ursula, was married to Buckingham’s oldest son.

Instead of seeing her daughter as chatelaine, Lady Salisbury was forced to remember that the pride and royal pretensions of Buckingham that had created the grandeur of Thornbury, had resulted in his execution for treason in 1521. His possessions were all forfeit to the Crown. Today, Thornbury is a luxury hotel. Much of the original Tudor building still stands, and it is well worth a visit, although you may have to save up to stay in one of the sumptuous rooms!

Once Mary was recalled from Wales permanently in 1528, she again spent most of her time near London. One of the houses she resided in frequently, right up until her accession as Queen in 1553, was the manor of Hunsdon (5), in Hertfordshire. It was built in the mid-sixteenth century by the Yorkist Sir William Oldhall. Oldhall’s son, John, fell at Bosworth and his lands were forfeit to the Crown, although later granted for life to Thomas Howard, 2 nd Duke of Norfolk, presumably to show royal gratitude after Norfolk’s victory at Flodden. It reverted to the Crown in 1524 and Henry VIII expanded it significantly. Edward and Elizabeth also lived at Hunsdon, and one of the portraits of Edward shows the house in the background.

On Elizabeth’s accession, she granted it to her cousin, Henry Carey, later Baron Hunsdon. The present building, extensively remodelled and reduced in size from the original, is in private hands. The adjoining church shows many Tudor features, and Mary is known to have acted as godmother to at least one local child.

Another palace associated with Mary’s youth is Hatfield (6), also in Hertfordshire, although for Mary, her time there was deeply unhappy. It was to Hatfield that she was sent to act as attendant to the baby Elizabeth, who had supplanted her. The original red-brick palace was built by John Morton, Bishop of Ely, and later Cardinal-Archbishop of Canterbury, who was one of the most dedicated supporters of Henry VII.

Morton’s palace, in a traditional square formation, was built around 1497. It was at Hatfield that Elizabeth heard of the death of Mary, and received the coronation ring from her sister’s hand. Only one wing of this is left, the remainder having been pulled down and the bricks used to create the fantastic Hatfield House of Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury. Salisbury’s house remains, set in wonderful parklands and gardens, and is open to the public.

Mary also spent time at Hertford Castle (7) – it was to Hertford that she was sent when Queen Katheryn Howard’s household was disbanded. She was ordered to join Prince Edward there. Hertford, originally constructed by Henry II, was granted to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and became a favoured home of the Lancastrian Kings and their wives, Katherine de Valois and Marguerite of Anjou. It was then granted by Edward IV to his wife, Elizabeth Woodville, but Richard III deprived her of it and gave it to Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham.

Confiscated following Buckingham’s rebellion, it was given to Elizabeth of York when Henry VII took the throne. Henry VIII extended the castle and built the gatehouse. Mary received the castle during Edward’s reign and spent considerable periods of time there. Hertford, too, became part of the lands of the Cecil Earls of Salisbury until it was given to Hertford Town Council. The gatehouse houses the Council’s offices and the grounds may be visited by the public.

In Henry VIII’s will, Mary was bequeathed income, but not land. This changed when the Regency Council, which interpreted Henry’s Will very liberally, made huge land grants to its members. Mary and Elizabeth were both included in the giveaway, although Mary received by far the greatest share. As part of her holdings, she was given both the manor of Kenninghall, and the castle of Framlingham. Both of these properties, in Norfolk and Suffolk respectively, had been confiscated from Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, following his attainder for treason. Kenninghall, an ancient manor, had been rebuilt during the period 1505-1525 and was a grand Tudor construction, with an H-plan layout and 700 acres of parkland.

Kenninghall (8) appears to have been one of Mary’s favourite residences during the period 1547 – 1553. It was to Kenninghall that she first rode when she heard of the death of Edward VI, to raise her affinity and resist the coup aimed at depriving her of her Crown. En route, she stopped at Sawston Hall (9) in Cambridgeshire, home of the Huddleston family. The old Sawston Hall was burnt to the ground by Northumberland’s men, within hours of her departure, but she paid for a replacement, which remained in the family until 1982. It is still in private hands, little changed since the 1550s, except for the addition of three priest-holes during Elizabeth’s reign.

With the high number of men joining her, and the need to have a stout castle, capable of defence should Northumberland bring an army against her, Mary moved from Kenninghall to Framlingham (10). Originally a Norman keep, it belonged to successive Earls and Dukes of Norfolk, until it was forfeited in 1547 and granted to Mary. During the previous decades, it had been extended with pleasure gardens and comfortable internal chambers. The nearby St Mary’s Church became a mausoleum for the Howard family, following the Dissolution of Thetford Priory.

In 1553, Mary restored both Kenninghall and Framlingham to the Duke of Norfolk, but they were forfeited again when the 4th Duke, Thomas, lost his head for plotting to marry Mary, Queen of Scots. The castle was used in the later sixteenth century as a prison for Catholic recusants. It is now in the care of English Heritage, and makes a fine day out for families.

On 1st October, Mary was crowned at Westminster Abbey (11) as the majority of her forbears had been since 1066. She was crowned with the same ceremony and accoutrements as a King, with the exception of also being given the consort’s sceptre to hold in her left hand, and not donning the spurs of knighthood, although she was belted with the sword.

Six months after her coronation, Mary was again called upon to defend her throne in the face of Sir Thomas Wyatt’s rebels. Whilst the rebels were encamped on the south side of the Thames, Mary rode to the Guildhall (12) in London, where she made a rousing speech, scorning to show weakness in the face of threats. The Londoners, who by and large, were probably as anti the proposed Spanish match as Wyatt, were impressed by their Queen and, cheering her wildly, defended the city against Wyatt’s men. The Guildhall today is still used for functions for the Corporation of London, most notably, the annual Lord Mayor’s Dinner. There is also an art gallery with a surprisingly wide range of work.

Having shown her power, Mary proceeded with the planned marriage, which took place at Winchester Cathedral (13) on 25 th July, 1554. The date was St James’ Day, presumably picked to honour the Patron Saint of Spain. Mary arrived in Winchester some days before the wedding and stayed in the Bishop’s Palace. After the ceremony, the royal couple spent around ten days in the city. Today, Winchester Cathedral, which has the longest nave in Europe, houses the tomb of the celebrated author Jane Austen.

By the beginning of the following year, Mary believed herself to be pregnant and withdrew to Hampton Court (14) for the birth of an heir. Sadly, her physical symptoms were not those of pregnancy, and, after months of agonising doubt and humiliation, she left Hampton Court to have a brief period of respite at Oatlands Palace. Hampton Court is, of course, one of the great Tudor palaces still open to visitors, even though much of the original was replaced 150 years after Mary’s time by her name-sake, Queen Mary II and King William III.

Mary’s health was never robust, and by the autumn of 1558 she was gravely ill with the influenza that had carried off thousands of her subjects. She died at St James’s Palace, (15) London. St James’s was built in the early 1530s on the site of a former leper hospital and the Tudor gatehouse flanks the south side of Pall Mall. It remains the official residence of the Sovereign – ambassadors are credited to ‘the Court of St James’. No monarch has resided there since 1837, however, several other members of the Royal Family have apartments there, although the Tudor and Stuart royal apartments were destroyed by fire in the nineteenth century. The Queen’s Chapel, designed by Inigo Jones, is sometimes open to the public.

Mary’s heart was interred in the Chapel Royal at St James’s, but her body was buried in Westminster Abbey, in the Lady Chapel founded by her grandfather, Henry VII. She lies there still. In her will, she requested that her mother be laid beside her, and that the two of them should be given an ‘honourable tomb or memorial’ for a ‘decent memory’ of the both. Neither of these wishes was carried out and Mary has no monument. The effigy above her grave is that of her half-sister, Elizabeth, who was moved there from her original location to make room for James VI & I.

This article is part of a Profile on Mary I available in paperback and kindle format from Amazon.

The map below shows the location of the places associated with Mary I discussed in this article.