Mary I: Life Story

Chapter 5 : Fighting for the Crown 1553

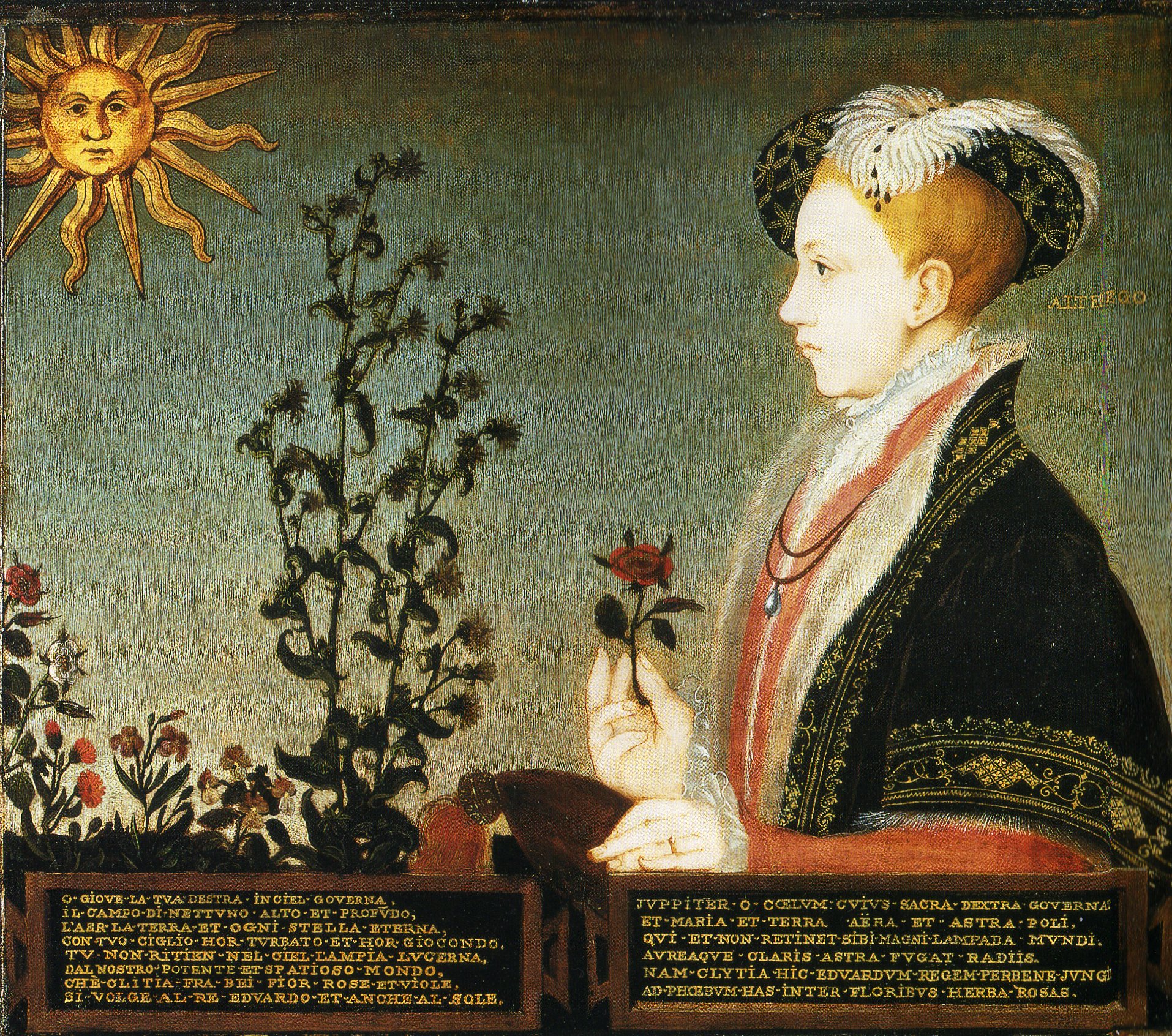

In February 1553, Mary visited London. She again made a show of strength, and was met by Dudley, now Duke of Northumberland, and a phalanx of courtiers who accompanied her to Whitehall and treated her almost with the ceremony due to a monarch. Edward was too ill to see her for several days, but both Mary and Elizabeth were assured it was only a cold and that he would soon be better.

Over the next few months, a plot was hatched to deprive Mary of her inheritance. Whether the idea was genuinely Edward’s or whether it had been suggested to him by Northumberland remains a moot point, but the upshot was that Edward drew up a ‘device’ for the succession, which would eliminate both Mary and Elizabeth, and replace them with their cousin, Lady Jane Grey, who, coincidentally or not, was married to Northumberland’s son, Guilford.

The Council, with varying degrees of delight and reluctance, signed up to the Letters Patent through which Edward attempted to put his desire into law. The legality of the action was questionable – Edward was a minor, so could not make a will, and it had been long established that Letters Patent could not overturn a Parliamentary statute. Nevertheless, the plan went ahead, supported by promises of French military aid. For Henri II (once Mary’s betrothed) the prospect of an England ruled by the Emperor’s cousin was to be avoided at all costs.

In early July 1553, Mary received word from London that Edward was ill and summoning her to attend him. Informed, though nobody knows by whom, of the plot against her, Mary left Hunsdon in the middle of the night, heading for her territories in East Anglia. En route, she stopped at Sawston Hall, owned by the Huddlestone family. After rising at dawn, hearing Mass and eating breakfast, she set off again, only hours before Northumberland’s men arrived. The house was burnt to the ground by way of a warning to others not to support Mary.

Back in the capital, Jane had resisted pressure to accept the Crown initially, but was persuaded that it was her duty to accept it to protect the Protestant faith, although she was adamant that her husband would not be king.

On 7th July, Mary received reliable information that Edward was dead, and that Lady Jane had been proclaimed Queen. She raced on for the security of Kenninghall. From Kenninghall, Mary began the fight back. She wrote to the Council, demanding she be proclaimed Queen, and assuring them of forgiveness if they immediately behaved themselves. Instead of accepting her claims, the Council responded, offensively reminding Mary of her illegitimacy, and thus inability to inherit the Crown, but assuring her that, if she accepted Jane as Queen, they would be glad to be of service to her.

On 13th July, Northumberland marched out of London to capture Mary. No-one else had been willing to go, and Northumberland’s parting words suggested that he had little trust in his fellow councillors, but the defeatist Imperial Ambassador wrote gloomily to his master, that Mary was likely to be captured within days. The Emperor declined to send any practical assistance to her.

The day before Northumberland had left, to deafening silence from the London populace, Mary had transferred, with a growing multitude of supporters, to the great stronghold of Framlingham in Suffolk, sending further letters to the Council and to the major cities, declaring her rights and demanding that she be proclaimed Queen immediately. Before long she had a sizeable army. A Lincolnshire man wrote to the Council:

‘Her grace should have her right, or else there would be the bloodiest day…that ever was in England.’

Almost as soon as Northumberland had departed, the individual lords of the Council, having second thoughts, sent secret messages to Mary, assuring her of their support. At Framlingham, more men came in, together with the Earls of Bath and Surrey, the Lord Wentworth and many of the gentry of eastern England.

Mary prepared to fight, and on 20th July she spent three hours reviewing her troops. Soon news came that Northumberland had surrendered in Cambridge, perhaps, at the last, unwilling to return England to the civil wars of the previous century, or perhaps aware that he had no hope of vanquishing Mary's increasing army. News reached London that Mary had been proclaimed Queen throughout East Anglia, and heralds were immediately sent out by the members of the Council who had hurriedly remembered their loyalty, to St. Paul's, to proclaim her in the City. The bells were rung and bonfires lit in the streets.

Mary, flanked by her supporters, entered London in triumph, to a tumultuous public welcome. She was joined at Wanstead by her half-sister, Elizabeth, who had done nothing to aid either of the contending parties. Dressed in purple velvet and cloth of gold, and followed by a huge train of peers and their ladies, as well as by the Lord Mayor and a choir of children, Mary rode to the Tower of London. There, she was greeted by a couple of old adversaries from her father's reign, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, whom she named as Lord Chancellor.

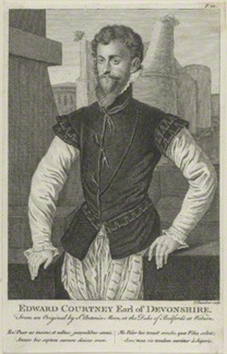

Mary also found Edward Courtenay, who had been imprisoned since the Exeter Conspiracy of 1539. Aged 26, he had spent all of his youth incarcerated. His mother, Gertrude Blount, Marchioness of Exeter, had always been one of Mary’s warmest supporters.

These prisoners were freed, but the Dukes and Duchesses of Suffolk and Northumberland, and the Lady Jane and Guilford Dudley remained in the Tower, transferred from the royal apartments to respectable lodgings elsewhere, rather than dungeons.

In due course, the two duchesses and Suffolk were pardoned, but Northumberland, despite a last minute reconversion to the Catholic faith, was executed, along with a couple of his lieutenants. Lady Jane and Guilford, having been found guilty of treason in a trial at the Guildhall, were detained in the Tower whilst Mary contemplated their fates.

The French were worried, and quickly denied having given any support to Northumberland and the Emperor hastily re-wrote history by telling his ambassador to inform Mary that he had been in the very midst of sending her aid when the good news of her bloodless succession had arrived.

On 1st October, Mary was crowned in Westminster Abbey, the first woman to be crowned as Queen Regnant in England (her young cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, had been crowned in Scotland some eleven years before.)

Mary I

Family Tree