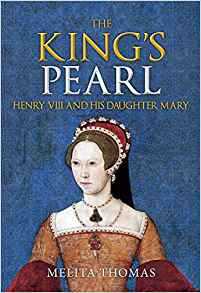

The King's Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary

A New Perspective

In any award for best father, most people would be unlikely to put Henry VIII in a short list, particularly in relation to his treatment of his eldest child, Mary. The usual perception of their relationship is that Henry, after loving her as a child, brutally separated her from her mother, banished her from his presence, tormented and harassed her into signing away her belief in her parents’ marriage and her own legitimacy, and then left her mouldering in the country until Katherine Parr persuaded him to restore her to the succession. The same narrative sees Mary as a terrorised victim, so cowed by her father’s bullying that her rage was repressed, only emerging when she became queen to explode in a violent persecution of Protestants, and a pathetic adoration of a chilly husband, who repeated Henry’s pattern of withholding affection.

Like most simplified narratives, there is some truth in it, but there is a great deal more to Henry and Mary’s relationship than is usually considered – and her personality was far more complex, and pro-active than she is often given credit for.

The King’s Pearl resulted from an interest in Mary dating back for forty years, from first seeing her as the villain in the BBC’s wonderful series, Elizabeth R, through the uninspiring A Level history lessons which repeated without critical analysis the misogynistic attitudes towards women rulers of both the sixteenth and the twentieth centuries. I was sure there was more to a woman who stood up against Henry for three long years, and who was prepared to take up arms against the might of Tudor central government, resulting in the only overthrow of government policy in the whole of the Tudor period.

It seemed I was not the only one to question clichés about Mary. In the last ten years there has been considerable scholarship devoted to her reign, and to untangling the propaganda of centuries of Protestant history, which, as well as misogyny, has had a strong anti-Catholic bias. I should mention here that I am not a Catholic and have no dog in this theological fight – but it has become very clear through the new work done by historians such as Dr Anna Whitelock, Dr Linda Porter, Judith Richards and John Edwards, that religious bias has dominated narratives of Mary.

The new thinking, however, has concentrated on Mary as queen, and I wanted to look further back. The discovery that, far from Mary being buried out of sight during the late 1530s and early 1540s, Henry was fond enough of her to commission rather sumptuous apartments for her at Whitehall was a starting point to re-evaluate their whole relationship.

As soon as I began my research, it became apparent that I had to see Henry and Mary as having two parallel relationships – they were father and daughter, but they were also political figures. For the first nine years of Mary’s life, their political ambitions (in so far as a child could have any) were the same – Mary was a princess, destined to make a grand match with a European power. Then, when Mary was nine, Henry began to consider a different future for her – that of a sovereign queen. He made the momentous decision to treat her as Princess of Wales (although she was not given the title officially) and send her to the Welsh Marches as previous heirs had been, to learn to be a monarch.

For three years, Mary internalised this position, and became used to the deference and respect given to the king’s heir – then when she was thirteen, she was confronted with the fact that her father was trying to set aside her mother, and declare her parents’ marriage illegal. She herself was not affected initially, in terms of rank, but separation from her mother followed, and in 1533, Henry declared she was illegitimate, and that his new daughter, Elizabeth, was his heir.

From this time forward, Mary and Henry’s political interests diverged. He wanted her to accept her demotion, and she was determined to maintain her position. Backing Mary was her powerful cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, although his support was always moral, rather than actual, and we can see from information to which neither Mary nor Henry was privy, that there was little likelihood that he would ever have intervened in England, even if Henry had moved beyond oppression of Mary, to outright punishment.

Eventually, Henry forced Mary to submit. Once she did, he was overjoyed, and hastened to renew his old, affectionate treatment of her. But they could never be quite unanimous in their politics again, and Mary was not always the obedient daughter she appeared to be.

To find out more, read The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary.

From 2nd October 2017, there will be a blog tour, as different facets of Mary’s life are covered on the following websites, finishing back here at Tudor Times on 14th October 2017.

3rd October: Medievalists.net

‘A Perfect Friendship’: You may think that Mary and Thomas Cromwell must have been enemies – but the evidence suggests another interpretation.

4th October: Sarah Bryson

An Interview with Sarah Bryson: Melita answers some interesting questions about her understanding of Mary’s character.

5th October: History of Royal Women

‘Your most humble daughter’: Mary and Queen Katherine Parr. Mary had five step-mothers. How did she and Katherine Parr feel about each other?

6th October: On the Tudor Trail

‘She is my death, and I am hers’. Was Anne Boleyn a wicked step-mother? Or was it more complicated than that?

7th October: Susan Higginbotham

‘A second mother’: Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury was the most influential woman in Mary’s life, after her own mother. What did Mary learn from her?

8th October: Henry Tudor Society

‘Mary, Princess of Wales’: So far, Mary is the only woman to have been treated as Princess of Wales in her own right. What did this mean, politically and personally?

9th October: Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide

'Mary and the Grey family': We all know that Mary faced a challenge for the throne from Lady Jane Grey, but how did the wider Grey family fit into her life?

10th October: Tudor History Org

‘A head filled with fantasies’: The Exeter Conspiracy cut a swathe through Mary’s relatives and friends – what did it mean to her?

11th October: Royal Historian

Review of 'The King's Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary'

12th October: Tudors Dynasty

'Pastimes for a Princess': How did Mary spend her time?

13th October: Amy Licence

'My Beloved Future Empress': Mary and the Emperor Charles V, cousin, betrothed, protector.

14th October: Tudor Times

‘Sibling rivalry?’: Mary and her Half-Siblings