Tudor Royal Propaganda

by Tracy Borman

‘We must not let in daylight upon magic’

Chapter 1: Introduction

In February 2021, Queen Elizabeth II will celebrate her 70th year on the British throne – her Platinum Jubilee – by far the longest reign of any British monarch. It will resonate not just in Britain but across the globe, thanks to the enduring popularity of, and fascination with British royalty (witness the success of Netflix’s award-winning series The Crown). Despite personal upheavals in the royal family, it continues to be held in high esteem.

The institution that the Queen represents is one the most iconic and enduring in the world. Elizabeth II can trace her descent to Egbert, the ninth century King of Wessex, which means that (excepting the Interregnum from 1649 to 1660) the British monarchy boasts a dynastic continuity that spans around 1,150 years. The ceremony followed at the Queen’s coronation in 1953 was largely the same as that used for the Anglo-Saxon kings 1,080 years earlier.

Despite the almost unimaginable change that has taken place during the twelve centuries of its existence, the British monarchy has survived, weathering the storms of rebellion, revolution and war that brought many of Europe’s royal families to an abrupt and bloody end.

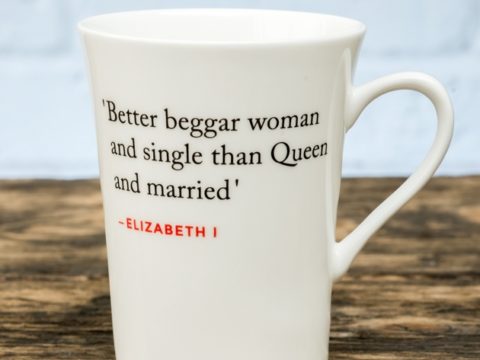

So what is the secret of its success? There is no single answer to that question. Partly it lies in the compromises that the Crown has had to make in order to survive: from Magna Carta in 1215 to the Bill or Rights of 1689, and much more besides. Partly it is the sense of tradition and continuity that the monarchy represents, which can offer much-needed comfort in a rapidly-changing, often frightening world. The achievements of individual monarchs have also played their part, from the great warrior kings such as William I, Edward III and Henry V to monarchs such as Queen Victoria who inspired the values of their age. In more recent times, George V and George VI made up for their diminishing political role by providing a national figurehead for the war effort. And the last six decades have proved that the decidedly unglamorous qualities of duty and dignity are highly prized, just as they were during the reign of the first Elizabeth, who sacrificed personal desire for her country.

But perhaps the most important ingredient for success is what we might today call PR. As has been shown again and again in the history of the British crown, the most successful sovereigns have been those who have skilfully managed their public image. Throughout the eleven centuries of its existence, the crown has been surrounded by an almost magical aura. The earliest coronation for which a detailed description survives, that of the Anglo-Saxon king Edgar in 973, conjures up a powerful image of the new king being anointed with holy oil to confirm his semi-divine status. The same ceremony has been performed, almost to the letter, during the eleven centuries that have followed. This has helped to bolster the mystique of monarchy; a sense of ‘otherness’ that keeps us mere mortals in thrall. As the Victorian essayist Walter Bagehot observed:

‘Our royalty is to be reverenced, and if you begin to poke about it you cannot reverence it…We must not let in daylight upon magic.’