Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens

A Review of the Exhibition

Rival Queens, Unrivalled Brilliance

The new blockbuster exhibition at the British Library finally opened in October after a year’s delay, caused by a pandemic, that had side-effects that the sixteenth-century would have recognised – closure of public spaces, the flight of the wealthy to the countryside, and the pervasive fear that nothing would ever be the same again. I’m glad to say that the British Library has managed to negotiate these difficulties and put on a show that was well worth waiting for. I’ve never seen such a wealth of artefacts gathered together to cast light on the reigns of Mary, Queen of Scots, the first female to be crowned as a queen-regnant in the British Isles, and her cousin, Elizabeth I of England.

The exhibition opens with a tiny ring, owned by Elizabeth, which has a tiny locket in the centre, opened to show the exquisite miniature of the queen herself, and a tiny representation of a her mother, Anne Boleyn. Whilst Elizabeth is never known to have discussed her mother, who was executed when Elizabeth was only two and a half, this deeply personal token suggests that the queen secretly mourned her.

Contrasting with Elizabeth’s loss of a mother she probably could not remember, is the loss that Mary suffered when she was sent away from the mother who had been constantly at her side in early childhood, Marie of Guise, for protection from her menacing great uncle, Henry VIII, who, having failed to persuade the government of Scotland to agree to a union of the countries through a marriage between his son, Edward, and Mary, tried to have her kidnapped. There is a letter from Mary to Marie, written when she was about twelve. This is not the only document from Mary’s French childhood – there are school exercises and poems, written in her fashionable italic hand, and family letters.

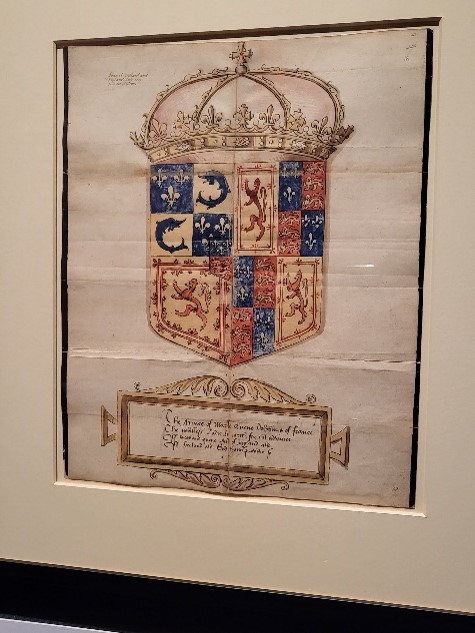

Included in the exhibition is a version of the drawing that sowed dissent between the cousins from the first days of Elizabeth’s reign – the drawing showing Mary’s coat-of-arms in 1559, when, at the urging of her father-in-law, she claimed to be the true heir to the throne of England, following the death of Mary I. Although it seems unfair to hold Mary entirely responsible for this, the distrust it engendered in Elizabeth and her ministers could never be eradicated.

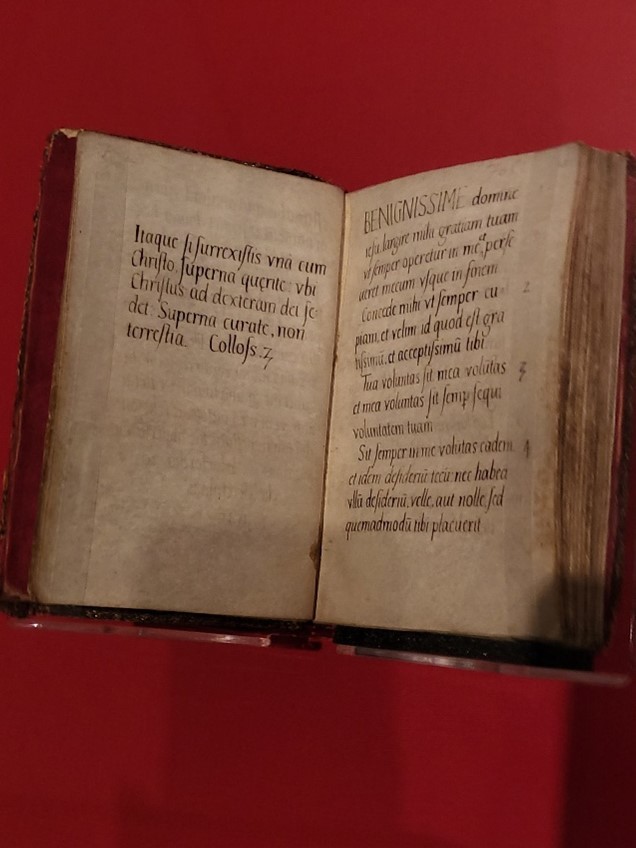

Whilst Mary was growing up in France, Elizabeth was, in the 1540s, forming a close relationship with her stepmother, Katherine Parr, and another of the gems of the exhibition is her trilingual translation of Katherine’s ‘Prayers and Meditations’, given to her father as a New Year’s gift – which, as well as showing Elizabeth’s intellectual skills, also showcases her talent for embroidery. Whilst embroidery was a much-prized skill for women, and, although there is no evidence of Elizabeth continuing it beyond girlhood, the exhibition has one of the great embroideries that Mary worked on to while away the interminable years of her imprisonment.

We are now very used to seeing reproductions of images. To see some of the most iconic paintings of the queens and their courtiers in the original can be startling - particularly with reference to size. The charming account portrait of Mary by Clouet with the rose pink gown on an ultramarine background is surprisingly small - yet every feature of Mary’s face is visible in exquisite detail. Particularly striking, is the portrait of Robert Dudley, Earl of Essex, Elizabeth’s dearest friend, whom she put forward (probably not seriously) as a potential husband for Mary. Unlike the tiny Clouet, this canvas is huge, and the earl looks out with an arrogant sneer. His physical magnetism is still obvious, even after four hundred years.

Some of my favourite exhibits were the maps – one of Elizabethan Lancashire, another showing the Thames, and a third, particularly interesting, of the beacon points for the Armada warning system. The maps are often from the collection of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, who was a cartography enthusiast and some show his annotations. There are numerous traces of Burghley in the exhibition – Mary’s implacable enemy, and Elizabeth’s political mainstay. His favoured method of making a decision – setting out all the pros and cons of a course of action – seems curiously modern.

The exhibition is arranged in chronological order, and once it reaches the period of Mary’s imprisonment in England (which was nearly half her life-span) the letters from Mary to Elizabeth, pleading for support, become more and more painful to see. I had the impression of a bird flapping in a cage – rather cliched, but the tone of desperation can be heard. Meanwhile, it is clear that Elizabeth was torn - perhaps not particularly sympathetic to Mary as an individual, but very aware that the tragedy of one monarch, was the tragedy of them all.

Another individual who seems to have been torn, was Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland, and, after Elizabeth’s death, James I of England. He was brought up in a hard school, and, however great his sympathy might have been for the mother he could not remember, it was never enough for him to seriously try to achieve her freedom, by agreeing the power-sharing arrangement that was put forward, or threatening England with war, if Mary were not freed.

A fascinating exhibit, beyond the artefacts themselves, is a short video showing how letters were ‘locked’ and sealed. This is followed with another video on the complex cryptography that Mary used to communicate with her followers – and then by the famous ‘gallows letter’ in which Walsingham permitted his clerk to add a forged postscript, to flush out the Babington Plot conspirators.

The curation team have done a truly wonderful job and the best way to appreciate their efforts is to go and see the exhibition! There is so much to look at, that even though I have been twice, I still bought the sumptuous catalogue, so that I can pore over the letters at leisure. It is an excellent work in its own right, with a series of superb essays by experts in the field.

Leave plenty of time – at least two hours, and ideally two-and-a-half, is needed to really appreciate everything (including how tiny everyone’s handwriting was…).

Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens is at the British Library from Friday 8 October 2021 to Sunday 20 February 2022.