Marie of Guise

Childhood and Youth in France 1515-1538

Marie of Guise (or Mary of Lorraine) belonged to a branch of the reigning ducal House of Lorraine. This gave her a social status next only to the royal family in France. Originally destined for a life as a nun of the ascetic Poor Clare order, when she was about fourteen, her uncle, the Duke of Lorraine, decided that her appearance and charm could be better used to build family alliances. She left the convent, and after a brief spell with her family, went to the court of Francois I of France in 1531.

In 1534 the King arranged Marie’s marriage to Louis d’Orleans, Duke of Longueville. The couple, of similar age, appear to have been happy and quickly had a son, named for the King. Whilst Marie was expecting her second child in 1537, she lost her husband, possibly to chicken pox.

Earlier that year, Marie had attended the wedding of the Princess Madeleine of France to James V, King of Scots. Madeleine was frail, and lived only six months after the marriage. James V was therefore looking for a second wife, and hoped to find another French bride to bolster his defence against his aggressive uncle, Henry VIII of England.

Marie, newly widowed, was reluctant to leave her son – her second child, another boy had died within a few months - but James and Francis would not take no for an answer. As an added spur perhaps, the alternative was marriage to Henry VIII, looking for a wife following the death of Jane Seymour. Marie is reported to have said that although she was big (nearly six foot), her neck was small.

Queen of Scots 1538 - 1542

Marie was married by proxy on 9th May 1538 and soon set out for her new country. Arriving in June at Balcomie, Fife, she and James were married at St Andrew’s Cathedral and she was crowned in February 1540.

Although Marie and James don’t seem to have been especially fond of each other they immediately performed their dynastic duty, with children born in 1540, 1541 and 1542. Heartbreakingly, the first two, James and Robert, died on the same day in April 1541.

Throughout James’ reign there had been continued tension with England, and the persistent low level troubles in the Border escalated into open warfare in 1542. James, mindful of his father’s death at Flodden, did not go into battle himself, but, following the miserable defeat at Solway Moss, fell gravely ill. He saw Marie at Linlithgow, where she was awaiting the birth of their third child, then moved to Falkland Palace where he died, a week after the birth of their daughter, Mary.

Queen Mother 1542-1554

Marie was not named as Regent. That honour went to the baby Mary’s heir – James Hamilton, Earl of Arran. Marie’s position, however, as mother of the Queen was important, and her support was sought both by Arran and his rivals. The Scottish nobles were divided between those who sought an alliance with England, and were willing to accept the English proposals for a marriage of the baby Queen to the young Prince of Wales, Edward, and those who preferred to adhere to the Auld Alliance with France. Religious affiliation was beginning to play a part in the choice. James V had been a traditionalist in religion, but reform was beginning to spread.

The majority view was that Scotland was safer in the embrace of France than in that of England and the marriage proposal from England was declined in 1543.This brought down the wrath of Henry VIII and he let loose his armies in the “War of the Rough Wooings.” During the next five years, Marie kept Mary either at Stirling, or, when that seemed too vulnerable, at Inchmahome Priory.

On Henry VIII’s death, the war became even more intense, ending with the decimation of the Scots army at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh on 10th September 1547. Nevertheless, the Scots held firm. They requested help from France, and Marie must have breathed a sigh of relief when the Treaty of Haddington in July 1548 was signed, which would make Mary Queen of France as well as of Scots and Scotland effectively a French protectorate.

Soon after, Marie parted with her five year old child, who was sent to France. Marie remained in Scotland to protect her daughter’s interests, although she was still not named as Regent. She was, however, one of a sixteen-strong Council put in place to advise Arran.

Regent of Scotland 1554 - 1560

Marie paid a visit to France in the period 1550-1551. She was reunited with both her children, only to lose fifteen-year-old Francois during her stay. In 1551 the Scots begged her to return to help the “execution of justice”, but although she accepted their request she was still without a formal role. Finally, in 1554, she was installed as Regent, but the task ahead of her was not easy.

The Reformation had made great strides amongst the Scots nobility, and there was growing resentment of France, and distrust of a French Catholic regent. England continued hostile. The new English Queen, Mary I, although a Catholic, was as hostile to France as any of her Plantagenet forbears had been, and although made no moves towards outright war, was happy to sow dissension in Scotland.

Marie made various attempts to present legislation to the Scots Estate related to improving trade and finances, but struggled to gain support. She carried on, reassured by the marriage of her daughter in April 1558 to the heir to the French crown, which reinforced the French desire to support (and control) Scotland.

Some (although not all) of the Protestant Lords joined together, calling themselves the Lords of the Congregation and demanding that church services be held in Scots, and Communion given in both kinds to the laity. In August 1558 there was open rioting (possibly deliberately incited) at a religious procession, despite Marie’s presence.

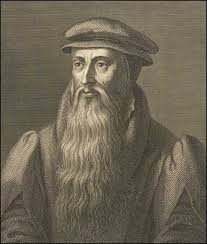

With her health deteriorating, Marie found resistance difficult. The return in early 1559 of the preacher Knox, an extreme Protestant and a hater of France, after eighteen months spent in the French galleys, exacerbated the situation. Knox was preaching not just religious reform but was undermining Marie’s authority, claiming that for women to rule was contrary to the law of God. Marie marched an army to Perth to capture Knox and re-impose order, but, outnumbered, had to retreat.

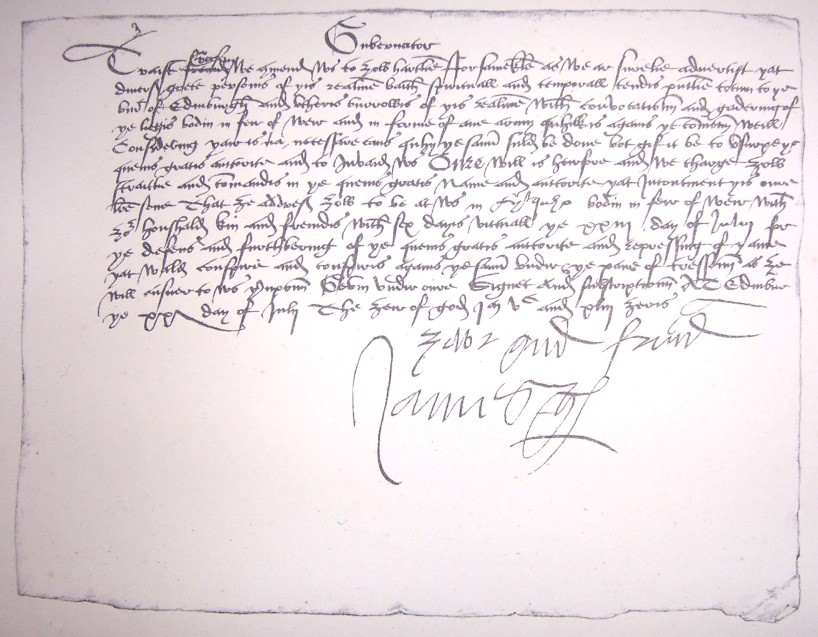

The Lords of the Congregation assembled an army in Fife, which Marie did not have the troops to resist. At this point she was still supported by the former regent, Arran. For Marie however, the only way she could put down armed insurrection was through the import of French troops. The Congregation occupied Edinburgh, and a burst of iconoclasm followed. Eventually, they withdrew, following an agreement signed with Marie on 23rd July 1559 at Leith, in which they agreed to recognise the authority of Queen Mary and her French husband, in exchange for freedom of worship. Not long after, Arran joined the Lords of the Congregation.

Marie sent desperate appeals to France. The Lords were on the march again, but Marie evaded capture. On 21rd October 1559 the Act of Suspension relieved Marie of the Regency and reinstalled Arran as head of a Council. Marie sought to continue the fight, despite deteriorating health, but on 22nd January 1560 the ships the Lords had requested from the new, Protestant, Queen of England, arrived at Leith, followed by an army. Marie tried to negotiate with them, but by June of 1560 she was sinking fast, and died on 11th June 1560.

Her body was shipped to France and buried at the convent of St Pierre Les Dames, Rheims.