Mary, Queen of Scots: Road to Fotheringhay

Mary lived in the delightful, if small, Renaissance palaces of Scotland, before being transported to the fairy-tale chateaux of France, and then, later, spending nearly twenty years in the English Midlands, as she was imprisoned in a range of isolated castles, and damp manor houses.

The numbers against the places correspond to those on the map here and at the end of this article.

Mary was born in the delightful palace of Linlithgow (1), west of Edinburgh. Today, only a shell remains, but enough to see why it was one of the Scottish monarchs’ favourite places. It is in the care of Historic Scotland, and open to the public.

The red sandstone palace was one of the most modern and comfortable of the Scottish palaces, and so suitable for the queen’s lying-in. Unfortunately, it was not the most easily defended of locations, so when Mary’s father, James V, died within a week of her birth, leaving her as queen, her mother, Marie of Guise, was concerned that Mary was exposed to risk of abduction. Danger might come from either the marauding English, or from her own nobles, eager to lay hands on the little queen, so that they could control the government.

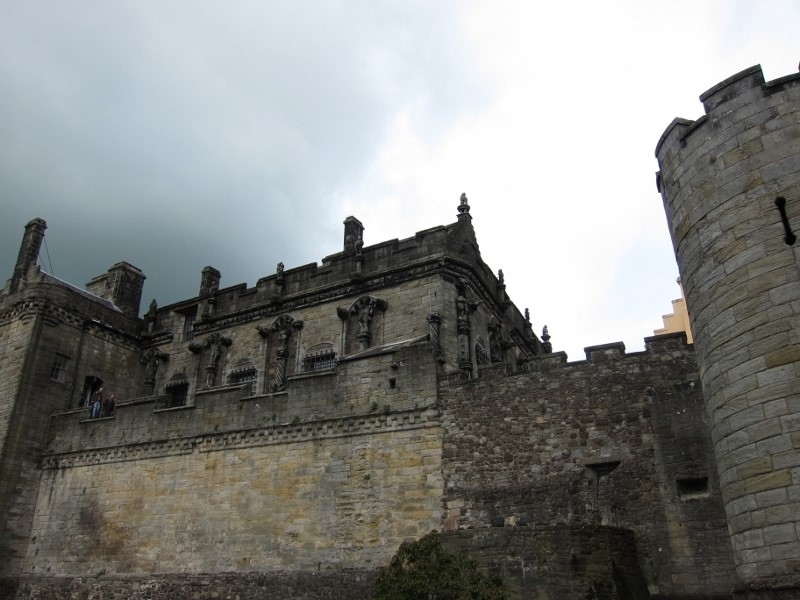

Marie was eager to move Mary to a more defensible location, but it was some months before the political situation was stable enough for her to do so. The location chosen, was Stirling Castle (2). Stirling is located close to a crossing point on the Firth of Forth, and throughout the mediaeval period, it was said that whoever held Stirling, could hold Scotland. The location has a bloody history – it overlooks the site of both the Battle of Bannockburn of 1314, and also of the Battle of Sauchieburn, where James III was killed, to be succeeded by James IV.

In the half-century before Mary’s birth, Stirling had been the subject of extensive renovations and new construction by her grandfather, James IV, and father, James V. These extensions included the King’s Old Building, the Great Hall, and the Foreworks, in the latest Renaissance styles. Mary spent most of her first five years here. She was crowned in the Chapel Royal, and it was also the scene of the most sumptuous celebration of her reign – the baptism of her son, James VI. The Chapel Royal now, is very different from how it looked in Mary’s day – then, it was a Catholic chapel, with all the typical ornamentation, stained glass and relics. With the Protestant Reformation, these were stripped away, and the Chapel today is a plain and elegant space.

Stirling Castle is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Scotland – run by Historic Scotland, it is open all year round. The main palace block has been restored to look much as it would have done when Mary’s mother, Marie of Guise, was Regent of Scotland, whilst Mary herself was in France. The colour schemes are very much brighter and lighter than you might imagine. Most beautiful of all the exhibits are the reproduced Flemish tapestries, woven at Stirling in a project that lasted thirteen years. They truly bring the past to life.

Even Stirling was not entirely safe for the young Queen of Scots. The Treaty of Greenwich, which had been agreed between the Regent, the Earl of Arran, and Mary’s great-uncle, Henry VIII, had envisaged Mary being married to Henry’s son, later Edward VI, but the Scottish Parliament declined to ratify the treaty, and instead, it was agreed that Mary would travel to France for her own protection, and marry the Dauphin. Aged five, she left Stirling and travelled to Dumbarton Castle (3), on the edge of Glasgow. Dumbarton, perched above the confluence of the Rivers Clyde and Leven is the oldest, continuously-fortified stronghold in Britain. Once the centre of the ancient kingdom of Strathclyde, by Mary’s time, it was being held by the Hamilton Earl of Arran. This was one of the bones of contention between the Hamiltons and the Stewart earls of Lennox, who had previously had possession of it. Mary sailed from Dumbarton in August 1548, after being trapped for some days by contrary winds. During the years of her personal rule, Mary forced the Hamiltons to cede Dumbarton, as punishment for a possible plot against her.

Dumbarton is another property managed by Historic Scotland. It is open all year round.

The treaty that agreed Mary’s departure for France had been signed on 7th July 1548 just outside Haddington (4). Haddington is now a small town in East Lothian, but in the late middle ages, was the fourth largest town in the country. It was a royal burgh, frequently visited by the Scottish monarchs and has seen its fair share of Scottish history. Some thirty years before the treaty, John Knox, who was to be Mary’s nemesis, was born there, and it was the subject of frequent attack by English forces heading for Edinburgh.

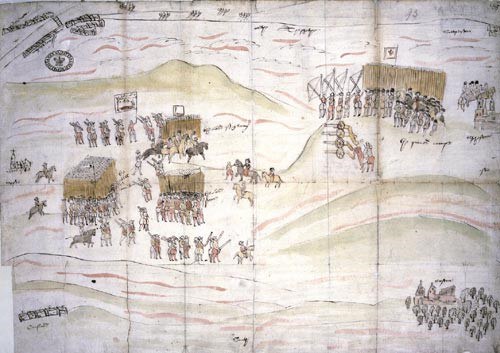

During the Wars of the Rough Wooing 1544 – 1548, Arran took Haddington back from the English after the Scots defeat at Pinkie, but it was re-invested by Francis Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. The siege of Haddington, which occupied the first half of 1548, saw Scots and French troops attempting to dislodge the invaders. It was during a visit to see the situation for herself that Marie of Guise signed the treaty. The Scots were unable to break the siege, but the English eventually withdrew for lack of supplies. The collegiate church of St Mary’s (the longest parish church in Scotland) had been badly damaged during the siege, but repairs were undertaken at the behest of Knox, in 1561, when it became the parish church.

Mary remained in France for thirteen years, returning in August 1561. She arrived at the port of Leith, to the north of Edinburgh, and after a short rest, was accompanied to her palace at Holyroodhouse (5). Holyrood Abbey had been founded by King David I, in 1128, as a house of Augustinian Canons. The name probably commemorates the piece of the True Cross (rood) owned by King David’s mother, the Queen (and St) Margaret. The abbey became the location of marriages and burials for the Stewart monarchs. James III and James IV married Margaret of Denmark and Margaret of England respectively, in the abbey, and James IV also began the construction of a royal palace. James V extended the palace buildings, and by the time of Mary’s birth, it was the chief royal residence in Edinburgh.

For Mary, it was probably the place in her capital that was closest to the elegant chateaux of the Loire, and it is the place where she spent the majority of her time, with her personal apartments located in the north-west tower. Unlike her two predecessors, Mary did not undertake any major building projects during the years of her personal reign, but she did have archery butts set up and a tennis court built at Holyrood – unfortunately, no traces remain.

Holyroodhouse was the scene of one of the most dramatic occurrences of Mary’s reign, when her private apartments were invaded by her estranged husband and a mob of violent nobles, who dragged her secretary, David Riccio, from her side, and stabbed him to death. Using her capacity for quick thinking, and her undoubted charm, Mary managed to turn her husband against his co-conspirators, and organise a midnight escape from the palace. Today, the palace (which is the official residence of HM The Queen, when in Scotland) is open to the public, and the room where the murder took place may be seen.

Whilst Holyroodhouse was a modern and elegant setting for Mary, when the time came for her child to be born, she withdrew into the more easily defended Edinburgh Castle (6). The castle, which looms magnificently over the whole city of Edinburgh on its granite outcrop, is another of the legacies of King David I. Built in the early twelfth century, the oldest building in Edinburgh is contained within its walls – Queen Margaret’s chapel, built in memory of his mother.

The majority of the castle that Mary knew was destroyed in the Lang Siege of 1568 – 1573, when the Queen’s Party, which hoped for the restoration of Mary, held out against the King’s Party, which favoured the continued reign of James VI, under the various regents, but was eventually defeated by the Regent Morton.

The heavy artillery fire demolished most of the mediaeval structure, although the birthing chamber where Mary bore James and the two outer chambers are still visible in the sixteenth century block – somewhat updated in the seventeenth century. Within this block are housed the Honours of Scotland – the crown jewels, comprising crown, sceptre and sword.

The oldest item, dating from 1494, is the sceptre given by Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) to James IV in 1494. The sword also dates from the time of James IV, but was a gift from Pope Julius II. The crown is the one made for Marie of Guise, from Scottish gold, for her coronation after marrying James V. It was then used for the crowning of Mary, as queen-regnant. Mary was only nine months old, so the crown was held over her by Cardinal Beaton. Mary’s coronation was the first occasion on which all three items were used together.

The Honours were used again for the coronations of James VI, Charles I and Charles II, hidden during the Commonwealth years, and then laid in the Parliament house to represent the monarch during the reigns of the later Scottish monarchs. At the time of the Union in 1707, they were hidden away, only emerging in 1818 following a campaign by Sir Walter Scott. There can be long queues to see the Honours, so arriving early and seeing them before the rest of the castle is recommended.

Various new buildings were constructed to enable the castle to be garrisoned to meet the threats of the Jacobite Rebellions of 1715 and 1745. Today, the castle houses the National War Museum, which gives a history of Scottish involvement in military affairs, at home and abroad – and commemorates the shocking brutality of the Battle of Culloden, as well as the high Scottish mortality rate in the Great War. The castle, is, of course, home to the annual Military Tattoo, in August.

Within a year of the birth of James, Mary’s world was turned upside-down. Her second husband, Lord Darnley (known on her orders as King Henry) had been assassinated, and Mary had been abducted, and married, either willingly or under duress, to the Earl of Bothwell, reputed to be the chief assassin. The breakdown in relations between Mary and her other nobles was so serious that she faced armed rebellion at Carberry Hill (7), near Musselburgh. The royal forces were inferior, but neither side was eager to give battle, and Mary agreed to surrender, believing that she would be treated honourably. Nothing could have been further from the truth, and she was paraded through the streets of the capital to cries of ‘murderer’ and ‘adulterer’.

The defeated and humiliated queen was taken prisoner to Lochleven Castle (8). Lochleven, controlled by the Douglas family, who were kin to the murdered Darnley, is situated in the middle of a loch. Mary was held under harsh conditions, and miscarried of twins within days of her arrival. Exhausted, terrified, and physically drained, she succumbed to the bullying of Lord Lindsay, and signed a deed of abdication on 24th July 1567. But Mary was resilient. Once her strength had returned, she used her famous charm to persuade two of the younger Douglas brothers to help her escape. Lochleven, also managed by Historic Environment Scotland, can be visited from April to October. Just as in Mary’s day, you need to take a boat to the castle, and so the limited capacity makes booking in advance advisable.

Once free, she soon had an army, and planned to move for security to the impregnable fortress of Dumbarton. She was intercepted by her half-brother, Moray, and the army of the rebel lords at Langside (9), now a suburb in south Glasgow, with no trace left of the battle field, only a nineteenth century commemorative monument.

Following the crushing defeat at Langside, Mary, in a move which hindsight shows was disastrous, slipped across the English border and into permanent imprisonment. Initially, she was treated as an honoured guest, at Workington Hall, then at Carlisle Castle. She was soon persuaded to move to Bolton Castle (10) some 75 miles further south, which would have made impossible any quick return to Scotland whilst the English government was considering its options. Bolton may be visited today.

Even Bolton was considered dangerously far from London, in an area of England that was still predominantly Catholic. Mary was moved further south, into the care of George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. He remained in post for nearly fifteen years – a job that wrecked his mental and physical health, his marriage to Bess of Hardwick, and his finances. Elizabeth, notoriously parsimonious, was reluctant to reimburse the costs necessary in guarding a queen, and Mary’s own income, as Queen Dowager of France, arrived sporadically, as well as being badly managed by her agents.

The main locations where Mary was housed were Tutbury (11), Sheffield (12) and Wingfield (14). Of all the places she lived, Mary hated Tutbury the most. It was an aging castle, some miles north of Burton-on-Trent, and Mary arrived on 9th February 1569 to find it damp and cold. Furnishings had been hastily sent from Sheffield, but could not hide the stench from the latrines underneath Mary’s chamber windows. The castle was (and is) part of the holdings of the Duchy of Lancaster, thus the personal property of Queen Elizabeth, but there is no record of her ever visiting it. Despite the many films on the topic, Mary and Elizabeth never met. The castle ruins make an attractive picture today.

In so far as Mary could prefer any location, Sheffield Castle was more appealing than Tutbury. The main castle had been improved by Shrewsbury’s grandfather, the 6th Earl, and there was also an up-to-date manor house in the park. Mary was housed in both, moving between them as they required cleaning. The castle was devastated during the Civil War: too damaged to rebuild, the owner, the 22nd Earl of Arundel (the4th Earl of Shrewsbury’s grandson), demolished the remains. Two rooms are visible from Castle Market, in the centre of the city of Sheffield. The ruins of the manor, which include elements of the long gallery, and the tower which housed Mary, were sold by the Duke of Norfolk to Sheffield City Council in 1953. It is now a visitor attraction, called Sheffield Manor Lodge.

Another of Shrewsbury’s properties where Mary was occasionally housed, was Wingfield Manor. Today, an impressive ruin in the care of English Heritage, in 1580s it was probably the most attractive of her prisons. Located about half-way between Sheffield to the north, and Tutbury to the south, it is in the lovely countryside around Matlock. Today, it can only be visited by prior arrangement.

In 1584, Shrewsbury was finally released from his duties as Mary’s gaoler. The task was given first to Sir Ralph Sadler, and then to Sir Amyas Paulet. The main location for her captivity in these last years of her life was Chartley, in Staffordshire, owned by Sir Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. The mediaeval castle being uninhabitable, Mary was lodged in Chartley Manor. The property was completely destroyed by fire in the eighteenth century.

It was from Chartley that Mary departed on her final journey to Fotheringhay Castle (15) the great Northamptonshire stronghold of her Yorkist ancestors. There, she was tried, and then executed in the Great Hall.

The map below shows the location of the places associated with Mary, Queen of Scots discussed in this article.