Francis Walsingham: Lost Places

Francis Walsingham travelled in France and Italy during his exile in Mary I's reign. He also visited France and the Netherlands in ambassadorial roles. in England, he seems to have stayed close to London and the court, rather than travelling further afield. Walsingham was a workaholic, spending long hours and days at his desk in his houses at Seething Lane or Barn Elms. Whenever he was forced to take part in Elizabeth I's many progresses, he complained of the expenses and the waste of time.

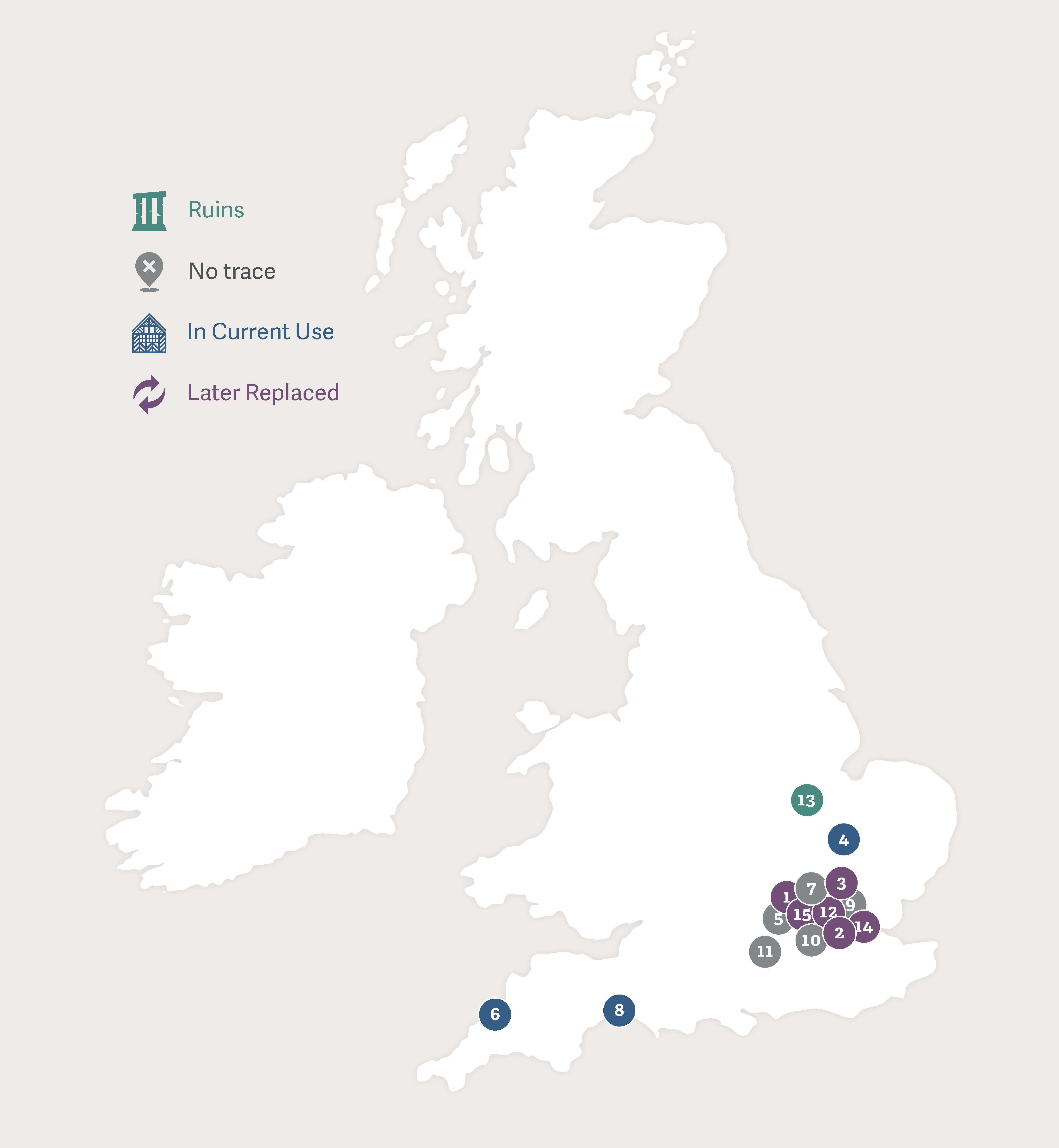

The numbers against the places correspond to those on the map here and at the end of this article.

Unfortunately, there are few places visible today where we can follow Francis Walsingham. Most of the places where he lived, worked or studied have long since been replaced by modern buildings, or even disappeared completely.

Walsingham was probably born in his parents’ house in Aldermanbury Lane, London (1). Aldermanbury is in the heart of the City of London, with a population of merchants, city dignitaries and lawyers. The church of St Mary Aldermanbury, first mentioned in 1181, and perhaps the location for Walsingham’s baptism, burnt to the ground in the Great Fire of 1666. It was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren, but damaged in the Blitz. The ruins were transported to Fulton, Missouri, and erected in the grounds of Westminster College.

The alternative location for Walsingham’s birth is the family’s country estate at Foot’s Cray, (2) near Chislehurst. The manor was purchased from John Heron, by Walsingham’s father in 1529, perhaps to enable the family to live near Walsingham’s uncle, Sir Edmund Walsingham, based at Scadbury, Chislehurst (another possible birth place for Walsingham).

Foot’s Cray, less than five miles from the royal palaces at Eltham and Greenwich, would have been convenient for London, with travel usually by boat. The watermen would have collected passengers at the bank of the Thames near Greenwich and rowed as far as London Bridge. It was dangerous to ‘shoot the rapids’ at London Bridge – that is, take a boat under the structure - because the currents could dash the craft against the piers, so most passengers disembarked and took another barge the other side. The Walsinghams would have disembarked and walked up what is now King William Street to Cheapside, where they would have turned west, then north towards Aldermanbury.

Walsingham inherited Foot’s Cray and its manor house but sold part of it, including the manor house, in around 1566 to John Ellis. The remainder, he sold some years later to John Gellibrand. The manor house was demolished and replaced in the Palladian style in the 1750s.

After his father’s death in 1531, when Walsingham was no more than eighteen months old, his mother, Joyce, nee Denny, married John Carey, brother-in-law to Mary Boleyn, once the king’s mistress, and now the sister of the woman Henry VIII sought to make his queen. John Carey was a groom of Henry VIII’s Privy Chamber from at least 1526, and was later the bailiff at the royal manor at Hunsdon in Hertfordshire (3).

The earliest mention of Hunsdon is from 1447, when Richard, Duke of York, received a licence to embattle it. Shortly after, it was in the possession of Sir William Oldhall, perhaps as a tenant of the duke. It came into the hands of Lady Margaret Beaufort, who, in 1503, exchanged it with Henry VII for the manor of Old Soar in Kent. Henry VIII undertook extensive works from the mid-1520s. During the 1530s and 1540s, whilst Carey was bailiff, it was frequently used to house the king’s children, Mary, Elizabeth and Edward, particularly the latter two, and it is probable that Walsingham became acquainted with them. It may be that his friendship with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, dated from this time as Robert was one of the boys appointed to be brought up with Prince Edward.

Elizabeth I granted Hunsdon to her cousin, Henry Carey, nephew of Walsingham’s step-father. The house passed through several hands, and was significantly altered in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is currently in private hands.

Walsingham went to King’s College, Cambridge (4), to complete his education. King’s was founded by Henry VI in 1441. It was to house a Provost and seventy poor scholars, to be drawn from Henry’s grammar school at Eton. Walsingham would have been one of the first generation of students admitted who did not previously attend Eton. The foundation stone of the chapel was laid in 1446, but building came to a halt when Henry VI lost his crown to Edward of York in 1461. Edward, now Edward IV, and his brother, Richard III, continued building from 1476. From 1485 to 1508, there was a hiatus, before Henry VII provided further funds, which enabled its completion by 1515 – a superb example of late English Gothic architecture. Henry VIII paid for the magnificent windows, which are replete with Beaufort and Tudor motifs.

The chapel today is one of the most visited sites in Cambridge, and the setting for the annual service of Nine Lessons and Carols on Christmas Eve. No matter how good a photograph you see of King’s College Chapel, the reality will astonish you with it grace and beauty. It is open to the public, but opening times are not easy to ascertain – check before visiting.

Walsingham left Cambridge without taking his degree, and moved to Gray’s Inn (5), London, for legal training. Gray’s Inn was one of the Inns of Court, where aspiring lawyers learnt common law, and the practice of pleading cases. During the 16th century, Gray’s Inn was one of the most fashionable inns for young men with court connections: Walsingham’s father had been a Reader there, and William Cecil, with whom Walsingham would work closely, was a member. Almost all the buildings that Walsingham would have known are long gone. They were located near the modern intersection of Gray’s Inn road and High Holborn, with new buildings added towards the end of the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth.

Several fires in the late seventeenth century destroyed the mediaeval and Tudor buildings. The new buildings were then severely damaged by the Blitz of 1941. A lone survivor from just after Walsingham’s period at the Inn, is the Hall, dating from 1559, although it too, has been heavily restored.

Walsingham spent much of Mary I’s reign abroad, but returned in 1559, to be elected to the Parliamentary seat of Bossiney (6) in Cornwall. Bossiney is a small village located in the far west, near the famous castle of Tintagel, which, although almost ruinous by Walsingham’s time, still had a constable and officers. Bossiney was probably enfranchised (that is, the burghers were given the right to return members to Parliament) in 1547, on petition from Sir John Russell, who, as Earl of Bedford, was Walsingham’s patron in the borough.

Bedford, and later his son, the second earl, used his influence to return radical Protestants for the county. There is no likelihood that Walsingham ever visited his seat. Bossiney was pronounced a ‘rotten borough’ and lost its members following the Great Reform Act of 1832. Today, it is a delightful rural village.

Walsingham married for the first time in January 1532. His wife was a widow, with a comfortable dower, and they leased a property known as Parkbury House (7), near Kimpton in Hertfordshire as their country home, perhaps to facilitate Walsingham’s position as Justice of the Peace for the county. Parkbury was probably leased from Eustace Suliard, but there is almost no information about the house itself, or even certainty as to its locations. We do know, however, that Walsingham’s wife, Anne Barnes, had a feather bed there, with a needlework valance and green and red sarcenet hangings. Waslingham retained the lease at Parkbury until 1579, when he purchased Barn Elms.

Having proved his worth to the government in the Parliament of 1559, Walsingham was again nominated by the Earl of Bedford for the seat of Lyme Regis (8), in Dorset. Lyme Regis, like Bossiney, was a borough, granted its borough status, which gave it the right to return members to Parliament, by Edward I.

Again, there is no record of Walsingham visiting the district, or concerning himself with is affairs. He was there because Sir William Cecil had been anxious to have his voice in the Commons, although there is no information about any part he may have taken in Parliamentary debate.

As well as the house at Parkbury, Walsingham and his second wife, Ursula St Barbe, had a house in London, in a district known as the Papey (9). Now in the Aldgate Ward of the city, near St Mary Axe, it was then in the Lime Street Ward. The curious name ‘Papey’, refers to the Fraternity of the Papey, founded in 1442 by Thomas Symmeson, the Rector of All Hallows London Wall, for the maintenance of poor priests, and endowed with a small parcel of land, and the use of the nearby church of St Augustine. The Papey and the church were demolished during the reign of Edward VI, and, presumably, replaced or reconfigured as houses. The Walsinghams lived here for some time – it was at this house that Walsingham interviewed Roberto Ridolfi in 1571. There is no trace of Tudor London left in the streets around St Mary Axe – most of it destroyed by the Great Fire of London of 1666, and subsequent reconstructions.

As Walsingham’s importance grew, with his appointment as Privy Councillor and Secretary to the queen, he needed a country property that was close to the court. Elizabeth did not like Hampton Court after she was ill with smallpox there in 1562, but she often stayed at Richmond. This may have been the reason for the Walsingham’s choice of a house at Barn Elms (10), or Barnes as it is now known. The property, which belonged to the canons of St Paul’s Cathedral, had been leased out continuously. In 1480, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Thomas Thwayte, leased it, then Sir Henry Wyatt took a 96 year lease from 1st March 1504. He sold his lease to Sir Thomas Smythe, probably during the late 1560s. The Walsinghams took over the lease not long after – their second daughter, Mary, was buried in the parish in 1579, aged about six.

Elizabeth I was entertained by Walsingham and Ursula at Barn Elms on three separate occasions: 22nd July 1577, 11th February 1583 and 26th to 28th May 1589. Walsingham’s biographer, John Cooper, argues for Barn Elms as the centre of Walsingham’s intelligence operation – there were 68 horses stabled there in 1589, far more than the family could have needed.

The queen took a reversionary lease from the canons of St Paul’s, to begin on the expiry of Walsingham’s interest in 1600, which she granted to Walsingham by Letters Patent, so it remained the family home. Frances carried it to her second husband, Robert, Earl of Essex, but Ursula probably retained a life-interest, as she died there in 1602. A hundred years later, the house was used by the Kit-Kat club, a Whig political and literary group, of which Walsingham would probably have approved, with its objectives of hard work, Protestantism and curtailment of royal power! Later, the house was extensively remodelled, but fell into dereliction, and was finally demolished in 1954, following a fire. The land is now open space, near the delightful London Wetland centre, dedicated to preserving wetland wildlife.

Barn Elms was not Walsingham’s only country house – he also had a property at Odiham (11) in Hampshire. Odiham today is a small market town, but during the middle ages, it was an important centre of royal power. King John constructed the castle between 1207 and 1214. Not long after it was constructed, it was captured by the French in the First Barons’ War, which sought to replace John with Prince Louis (later Louis VIII) of France. It later played a part in the Second Barons’ War, as the stronghold of Simon de Montfort. Reverting to the crown, the manor was granted to successive queens-consort: Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I; Isabella of France, wife of Edward II, Philippa of Hainault, Edward III’s queen. During Queen Philippa’s tenure, King David of Scotland was imprisoned in the castle. Anne of Bohemia, Marguerite of Anjou and Elizabeth Woodville, wives of Richard II, Henry VI and Edward IV respectively, also held it in dower.

A house was built on the manor at some point, and it was probably this that Walsingham leased, perhaps from Lord Chidiock Paulet (son of the Marquess of Winchester), who held it for 50 years from 1558. Meetings of the Privy Council were held in Odiham In 1576 and in 1591, and it is tempting to think that the first took place at Walsingham’s house. He was certainly living there in November 1578, as he invited Leicester and Leicester’s brother, the earl of Warwick, to ‘a Friday’ night’s drinking.’

At some unknown time, Walsingham left his house in Aldgate Ward, and took another, presumably larger, property at Seething Lane (12). Again, there is no trace of his house – but he is remembered in the name of the office block built in the vicinity – Walsingham House. Later, Samuel Pepys, the seventeenth century diarist and naval administrator, lived in the same street. Walsingham would have approved Pepys’ diligence, although what he would have thought of Pepys burying his wine and parmesan cheeses in the garden for safety during the Great Fire, is anyone’s guess. Today, there is a secluded garden, pleasant to visit, out of the bustle of the City of London.

In 1586, Walsingham was one of the Privy Councillors who attended the trial of Mary, Queen of Scots, at Fotheringhay Castle, in Northamptonshire (13). He had distrusted the Queen of Scots for thirty years, and her condemnation for treason was, in his view, long overdue. Without his painstaking attention to detail, his hours of methodical investigations, and, perhaps, his schemes to entrap her, Mary might well have lived on.

Despite the Queen of Scots’ execution in 1587, England was not safe, and Walsingham’s long-prophesied Spanish invasion attempt took place in the summer of 1588. He was deeply involved in all of the activities relating to provisioning the army and the fleet, but took time to travel to Tilbury (14) to the muster that Queen Elizabeth attended, and where she made her famous speech (although the truth of what she actually said has been disputed). It was at Tilbury that he probably last saw his old friend, the earl of Leicester, who travelled from Tilbury towards Buxton for his health, but died en route.

Walsingham, too, was growing frail, and in declining health. He continued a punishing work schedule, but had to take time off during 1589. Elizabeth was not especially sympathetic, but agreed that, when a replacement had been found, he might retire. But he had left it too late. In April 1590, he died, and was buried in a very quiet ceremony at St Paul’s Cathedral (15), sharing a tomb with his beloved son-in-law, Sir Philip Sidney. Later, Ursula was laid next to him. St Paul’s was more-or-less destroyed by the Fire of 1666, and the only memorial to Walsingham is a modern plaque.

The map below shows the location of the places associated with Francis Walsingham discussed in this article.