12. The Book of Hours of Anne of Brittany

Tudor & Stewart World in 100 Objects

Books of Hours were treasured possessions during the Mediaeval period, and the Breton, French and Burgundian nobility were some of the most avid commissioners

of such works. Read more here

Anne of Brittany’s mother, Marguerite de Foix, owned a Book of Hours, probably commissioned in Paris, which followed the Use of Paris (that is, the liturgy as commonly followed in Paris. Before the Council of Trent, ‘Uses’ differed across Europe). Marguerite’s Book lists the various Breton saints, and contains a prayer in hope of a son to be born to Marguerite and Francis – with the implication that Anne had already been born.

The prayer for a son was not answered – many thought that Francis was being punished for his neglect of both his wives, and his philandering ways. Anne thus became heir to a duchy that the French crown coveted.

Marguerite’s Hours may be found in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Anne’s mother died when Anne was only nine, but she seems to have inherited the characteristics for which Marguerite was praised in Brittany – she was ‘fair, prudent and discreet’. Anne certainly inherited, or imbibed, the piety of Marguerite. Throughout her life, she gave generously to churches, monasteries, shrines and works of benevolence.

Anne commissioned her Great Book of Hours around 1500. It took some eight years to be completed, and is considered one of the finest examples of the genre, although one of the last of the great mediaeval manuscripts. The Master who created it was Jehan de Bourdichon (c. 1457 – 1521). Probably a native of Tours, he studied under Jehan Fouquet, the earliest known exponent of portrait miniatures.

Bourdichon was one of the most successful artists at the French court – as well as Anne’s Book of Hours, he painted portraits, designed coins, stage-managed court ceremonial and even, in the last year of his life, designed the French tents for the Field of Cloth of Gold, in 1520, where Anne’s daughter, Claude, met the King and Queen of England. The French royal accounts record regular payments to him - including maintenance of the mule on which he rode about royal business.

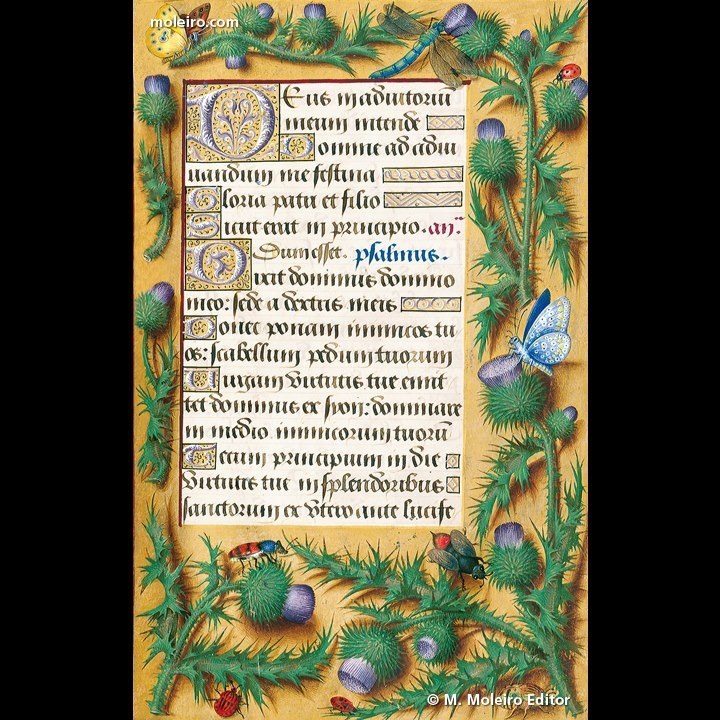

Although building on the traditional Flemish practice of floral borders, Bourdichon gave his borders increased botanical verisimilitude – as can be seen in this page below, compared with the stylised page in Marguerite de Foix’ Book above. In all, Bourdichon drew some 337 different plants – possibly from life in the chateaux of the Loire where Anne customarily resided. They were often labelled with their French and Latin names, the former in gold on a border at the bottom of the page, and the latter in scarlet at the top.

The Book follows the Use of Rome, and is some 238 pages, with twelve calendar illustrations, 49 full page illustrations (called miniatures, regardless of size), of both Old and New Testament figures, two pages of heraldic designs, 300 borders, and numerous initials,

One of the great delights of the Book, is the pictures of Anne herself. The best known image is that of Anne being presented by her patron saints – St Anne (mother of the Virgin) and Anne’s birth saint; St Ursula (not St Margaret as is sometimes suggested), carrying the ermine banner of Brittany and St Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine, who allegedly discovered the True Cross, and brought it to Europe. St Ursula is supposed to have been the daughter of a King of Dumnonia (in south-west Britain) betrothed of the governor of Armorica (the Roman name for Brittany), who decided to make a pilgrimage before settling down to matrimony. She and her accompanying 11,000 virgins, were massacred by the Huns.

Anne also appears, seated in a garden, in the illustration for April.

The name the ‘Grandes Heures’ indicates that the Book was larger than the usual Books of Hours, which could be easily carried on the person. Anne’s Great Hours are 30 x 19.5 cm (11 ¾ by nearly 8 inches). For personal devotional purposes, Anne had three more Books of Hours – the Petite Heures, in the Bibliothèque Nationale, a Très Petites Heures in the Pierrepoint Morgan museum in New York, and another, very tiny Très Pettites Heures, also in the Bibliothèque Nationale.

The work was finally completed and presented to Anne in the early spring of 1508. She issued an order from Blois to her treasurer to pay her ‘well-beloved’ painter, Bourdichon, 1.050 livres tournois for ‘illuminating richly and sumptuously a great Hours for our use and service’.