Books of Hours

During the late Middle Ages and Renaissance period, one of the most coveted items a literate person could own was a Book of Hours. Books of Hours were designed to aid lay people in the practice of their religion, by collecting biblical texts, prayers and elements of the liturgy for them to read throughout the day, emulating the ‘Hours’ or regular services of the religious life.

Members of religious orders repeated the Divine Office, divided into seven canonical ‘Hours’ each day, beginning with the combined Hours of Matins and Lauds, recited between midnight and dawn, then at three hourly intervals, Prime, Tierce, Sext and None, with the final Hours of Vespers and Compline in the evening. Time-keeping was more fluid then than it is now, and the recitation of the Hours would vary with the seasons and the light.

From the eleventh century, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary was added to the canonical Hours. This was taken up with enthusiasm by the laity as the cult of the Virgin became an enduring element of popular devotion and the Books of Hours commissioned over the succeeding centuries had the Little Office at their heart.

Each Book of Hours had three elements: the essential, the secondary, and the accessory. The essential consisted of the perpetual calendar, showing the fixed and moveable feast days and saints days – the most widely venerated saints would be listed, together with saints popular in the region the Book was created, or especially meaningful to the owner. Nearly everyone prior to the Reformation had a saint’s name, and would direct their prayers to that ‘patron’ saint for intercession with the Divine. Hence, girls called after a variant of Margaret would seek the protection of St Margaret of Antioch, or, in Scotland, the Scottish queen, St Margaret. The most popular boys name in England was Thomas – either for the Apostle, or for St Thomas Becket.

Customarily, the major feast days in each month would be marked with gold or red lettering. The calendar was numbered, not with the days of the month in consecutive numbering as is the modern practice, but by reference to the ‘kalends’ or first of the month; the ‘nones’ (the fifth or seventh of the month) and the ‘ides’ (the thirteenth or fifteenth). The calendar also showed the ‘golden number’, used to calculate Easter.

Generally, each month covers the right-hand-side of the open book (the recto) and the left-hand-side of the following page (verso). The month pages were decorated with activities suitable for the month – harvesting in June, ploughing in October, for example, or the zodiac sign.

Following the calendar, came the Little Office, the Penitential Psalms, the Litany, the Office of the Dead and the Suffrages of the Saints.

The secondary portion contained passages from the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John which refer to the coming of Christ, followed by the Passion as described in John. There were then additional prayers to the Virgin, and other Offices, such as that of the Hours of the Cross or the Fifteen Joys of the Virgin, might follow. The final element, the accessory, contained more Psalms and prayers.

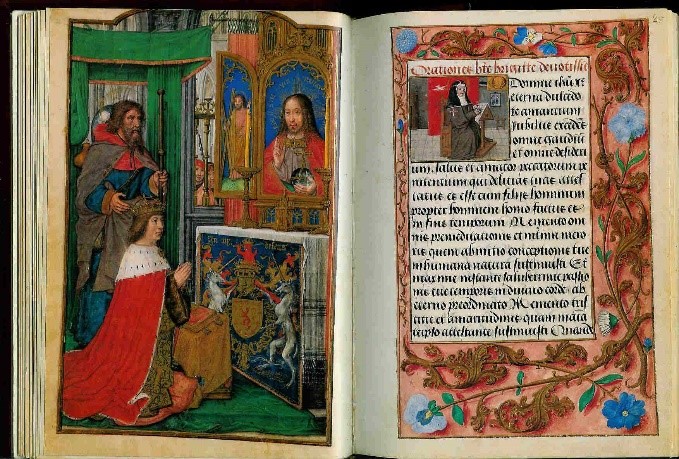

By the late fifteenth century, Books of Hours were so popular that centres such as Paris and Bruges produced them en masse. There were several stages to production – the acquisition of the vellum, the ruling of lines, the writing of the text, then the creation of the borders and ornamentation, before the final addition of the illustrations – called miniatures, regardless of size.

Higher up the social scale, Books of Hours were individually commissioned, frequently as a bride-gift from the husband for his new wife, and the level of decoration, the number of colours used in the illumination, and the quantity of gold, silver or expensive lapis blue used, depended on what the purchaser could afford.

The Books were often personalised by the depiction of the owner and his or her family, coats-of-arms, and symbols relating to the individual. For example, the Book of Hours of Anne, Duchess of Brittany and Queen of France, shows Anne herself, together with her husband and children. Queen Anne paid 600 gold écus for its decoration.

The Books were further individualised by the owner writing notes in them, sometimes recording events – such as the recording of the birth of her granddaughter in 1489 by Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of King Henry VII. Often, friends or lovers would write verses to each other, an example being a loving exchange between King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn.

Books of Hours were prized possessions, handed down through the generations and often refurbished and recovered.

With the coming of the printing press, many Books of Hours were mass-produced and their popularity in this new format continued. In Protestant countries, which eschewed excessive devotion to the Virgin, they were superseded by prayer-books, family Bibles and almanacs.