Mary Queen of Scots House

A mediaeval ‘bastel’ or fortified town house, where Mary, Queen of Scots took refuge during an illness in 1566.

Jedburgh itself (known to Mary as Jethart) is an ancient town, about ten miles north of the now-fixed border, but once a frontier town. The ruins of the magnificent abbey, founded by King David I lour over the town, and the street pattern is obviously mediaeval.

On the south side of the town, a five-minute walk from the free car-park (full marks to the Town Council for that) is the Mary Queen of Scots House. It is to here that Mary was reportedly carried when she fell desperately ill in 1566, not long after the birth of her son.

The house is not large – a three-storey construction in warm gold sandstone, constructed in an L-shape. Entrance is free, but donations are, of course, welcome.

The entrance is into what was probably a semi-external guardroom, which would have protected the inner house. Although it was a probably a merchant’s house, times were violent, and Jedburgh had been stormed and razed to the ground many times by English armies or marauding revivers.

The ground floor, which would have been the quarters for servants and guards, in Mary’s time, is devoted to the shop, selling the usual selection of books on Mary (which are legion) and other souvenirs. The visit begins up a fairly wide staircase, which turns back to debouche at the bottom of spiral staircase, with the entrance to three other rooms in the bend. At the bottom of the first stair is a facsimile of the warrant appointing a James Hamilton 2nd Earl of Arran, as the Governor of Scotland, for the infant Mary.

The rooms on the upper floor are plain – two were wainscotted in the nineteenth century but the third, which is labelled Mary’s bedroom, is whitewashed stone. This room projects to the west of the main block and although small for a queen’s chamber was probably a reasonably comfortable place for Mary to be nursed from the mysterious illness that struck her down in 1566. In one corner is a small cannon, given by the queen to the Kerr family. There are also some some seventeenth and eighteenth century portraits of the queen.

In the central rooms on this floor, directly over the shop, there is a series of placards telling the story of Mary’s life, again interspersed with pictures. In the third room, over the entrance area, is a useful display, called The Rogues Gallery, which summarises the lives and roles of the people in Mary’s story. Seen together the whole sad litany of broken trust and betrayal that characterised the period is laid bare: the husband who murdered her secretary, the cousin who executed her, the English ministers who were determined on her death and the half-brother who coveted her throne. But there was loyalty and love too, from her indefatigable mother, Marie of Guise, her minister, Maitland of Lethington, who despite his Protestant convictions supported her to his end, Lord Seton and her four Maries.

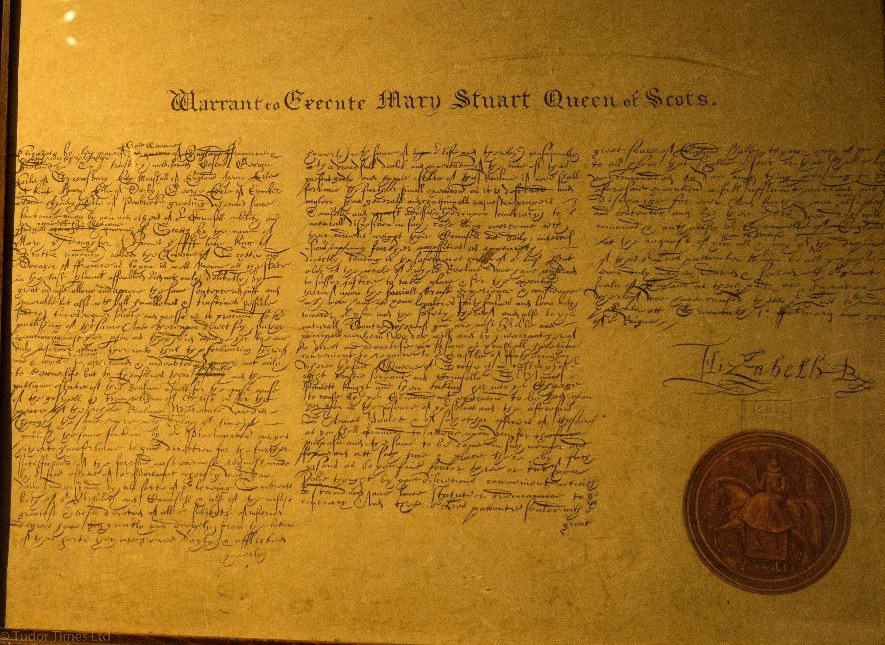

The next floor has two further rooms, the same size and shape, and with more facsimiles and pictures, including a a copy of the death warrant, with Elizabeth’s characteristic flourishing signature. The original no longer exists, but a copy was held by Henry Grey, Earl of Kent, who was one of the judges at Mary’s trial, and is now in the Lambeth Palace Library. This version is a transcript of that.

There is a rather gruesome death mask – coloured to show how Mary looked in life, although it has been given auburn hair, when Mary’s had turned white by the time of her death.

In the Last Letter Room, there is also a facsimile and translation of her last letter to Charles IX, lamenting that she had been refused the consolation of her religion at the end, and requesting him to pay her servants.

There is a tiny lock of what is apparently Mary’s hair, discovered in a bureau in Holyroodhouse Palace in the late eighteenth century. I am sceptical, as it describes the find as being contained in an envelope – envelopes were not invented until the mid-nineteenth century. However, the writing found with it, describing the lock as her own, is apparently in her authenticated writing. The small scrap of hair is of a bright red-gold.

Another treasure is a shoe, said to have been discarded by Mary because the heel broke, but preserved by the Allen family of Jedburgh.

There is also a very interesting facsimile of a letter from Mary, dated 25th September 1566, commanding the presence of the Laird of Cessford, in her Justice Ayre tour of Teviotdale, as the area surrounding Jedburgh was known.

The last room, up in the top floor of the wing that housed Mary’s own room is a small chamber n which her ladies apparently stayed whilst tending to her, probably including those of her Four Marys who were as yet unmarried.

The gardens outside the house are not extensive, but are extremely neatly kept, and were beautifully colourful in late August, when we visited. In one far corner is the remnant of an eighth century Anglican cross – much worn by the weather.

Whilst the Mary, Queen of Scots house is not large or grand, it is well laid out, and the artefacts tastefully displayed. Its interpretation is neither violently partisan nor excessively sentimental, but gives a clear and considered outline of events from which the viewer can make his or her own judgement.

Mary, Queen of Scots

Family Tree