The Will of Lady Margaret Douglas

Chapter 1: Bequests

Lady Margaret Douglas’ will makes interesting reading, and tells us a bit about Margaret, her relationships with her servants and also with two of the most important figures at Elizabeth’s court, Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley, and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester.

Margaret made the will in the spring of 1578 (although she dated it 1577, as old style dating was still in use). By this time, all her children had died, and she had only two grand-children, James VI, King of Scots, and Lady Arbella Stuart. She had urged the Scots government to recognise Lady Arbella as Countess of Lennox, but the Regent of Scotland, the Earl of Morton, had refused, and the lands and revenues of the earldom had reverted to King James.

At the time of her death, Margaret was living in Hackney, a country suburb on the edge of the City of London. Although the extensive lands that had been settled on Margaret and her husband, Matthew Stuart, Earl of Lennox, had not formally been confiscated, as despite various periods of imprisonment, no actual charges had been brought against them, the income and control had been sequestrated by the government. Only her lands at Settrington in Yorkshire were in her hands, or those of her appointees.

For a woman who was the daughter of a queen-consort, half-sister of a king, and close friend of a sovereign Queen, as well as mistress of an estate third only to that of the Crown in the north of England, Margaret had surprisingly little to leave.

As was customary, she began by bequeathing her soul to Almighty God. She chose to be buried in Westminster Abbey – this is, in itself, Margaret’s clearest statement of her belief in her royal lineage and the claim to the throne of England that she passed on to her descendants. Her beloved husband, Matthew, Earl of Lennox, had been buried in Scotland, following his assassination, but she chose to lie with her mother’s family – the Tudors.

Westminster Abbey was the burial place of her grand-parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, her cousin, Mary I, and her other cousin, Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk. In due course, Elizabeth I, James VI & I and Mary, Queen of Scots (Margaret’s niece) would all lie there. It seems that Elizabeth had no objection to Margaret being interred in the royal chapel, and in fact, ended up paying for the ceremony, as Margaret’s possessions could not cover her debts and funeral expenses.

Margaret’s grandson, James VI, received her new black velvet bed. This seems rather a bizarre bequest, but beds and their furnishings were extremely expensive, and rather a status symbol.Bed chambers were more public than they are now, and it was perfectly normal for guests to be received there. A smart set of hangings for the bed was important. Black velvet, too, was very pricey.

Her next major bequest is that of her sheep to Thomas Fowler – again, somewhat surprising to think of a Countess noting her sheep, but they were probably the next most valuable thing she owned, and great ladies in the sixteenth century were closer to estate management than their Victorian counterparts.

Margaret clearly trusted Thomas Fowler, although there are indications in other records that he was actually reporting on her activities to both Burghley and Leicester – it is difficult to be sure, as factors, stewards and other senior servants often worked for several people – employment not being so fixed as it now is. He had certainly been instrumental in organising the match between Darnley and Mary.

Margaret also left Fowler her collection of clocks, watches and dials. Clocks, too were extremely valuable and fashionable items, only becoming indoor, table-top pieces, such as we now have, in the final quarter of the fifteenth century, when the spring mechanism was invented. They were often owned by kings or nobles as manifestations of wealth and sophistication. This mention of a collection of time-pieces, together with a comment on Margaret in the 1550s, that she had amassed many relics and icons, suggests that she had the nature of a collector.

Leaving items of such value to Fowler, implies a warmer relationship beyond the fact that she owed him money. Her trust in him is indicated by his appointment as her executor.

As well as executors, it was usual to name overseers of a will. Margaret chose the two most powerful men in Elizabethan England – William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Elizabeth’s closest counsellor and Lord Treasurer, and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the Queen’s closest male friend. These two men had been the recipients of many letters from Margaret, usually relating to requests from her to speak favourably of her to the Queen, but we can probably infer that they were also her friends. Burghley’s wife, Mildred Cecil, had been one of the ladies sent to break the news of Darnley’s death.

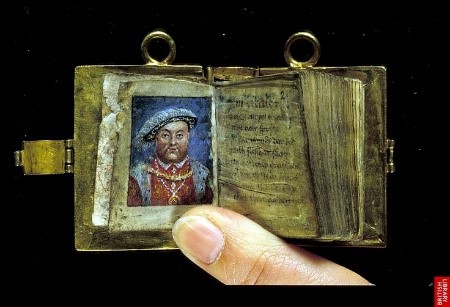

Leicester had promoted Margaret as a possible successor to Elizabeth in the early 1560s, rather than the more Protestant candidate, Lady Katherine Grey, and it was with Leicester (amongst others) that Margaret had been dined three days before her death. Her bequest to him of her pomander beads, as well as of her ‘tablet’ of Henry VIII, suggests a personal affection. A tablet might be a small book, or a picture. The illustrated book, now in the British Library, shows the type of artefact in question.

Finally, her jewels were to be given to her grand-daughter, the Lady Arbella, on her marriage, or when she attained the age of fourteen. So far as is known, these jewels did not include the famous Lennox Jewel, although there is no inventory, so we cannot be sure.

It seems that Arbella did not receive her bequest. In 1590, there was a request to King James to release goods seized from the estate of Thomas Fowler, in satisfaction of a debt to the Earl of Lennox.

‘Sundrie tymes I have moved the King and Lord Chancelour that the jewelles late in the handes of Thomas Fowler, deceased, and appertayning to the Lady Arbell, might be restored to her.’

Margaret’s most important legacy, however, was her royal blood – it was a positive legacy for James, but caused Lady Arbella to live a sad and constrained life.

Lady Margaret Douglas

Family Tree