Mary I: A Controversial Marriage

Chapter 2 : Whom Should the Queen Marry?

A husband could be chosen either from the nobility of England, or from a European prince. Marriage to a subject had occurred in 1464, with the wedding of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, and, of course, between Henry VIII and four of his wives, but such marriages were unknown outside England, and had not generally proved that popular in the country. Certainly Edward IV’s marriage had caused huge resentment.

If Edward IV’s relatives and advisors had been horrified at the promotion of a subject, and the rewards and preferment that Elizabeth Woodville’s family received, how much more would a marriage to a man who would then, in the eyes of the nobles, become king, have been resented?

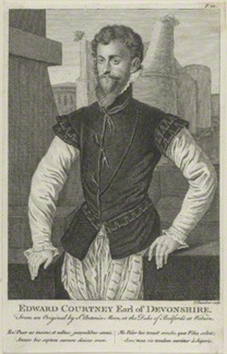

In any event, there were few home-grown choices who were remotely possible. The only males with royal blood were Edward Courtenay, the great-grandson of Edward IV; Reginald Pole, great-nephew of Edward IV; Henry and George Hastings, 3x great-nephews of Edward IV; and Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, grandson of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots.

Lord Darnley and George Hastings were both around thirteen so completely unsuitable and Henry Hastings was married – to the daughter of the Duke of Northumberland. That left Courtenay, aged twenty-six and Pole.

Courtenay had been sent to the Tower of London at the age of eleven, following the Exeter Conspiracy, which resulted in the execution of his father, Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter. He had only been released on Mary’s accession.

Courtenay was favoured by a significant group of Mary’s Council, including her Lord Chancellor, Stephen Gardiner, who had become fond of the young man when both were in the Tower during Edward’s reign. Courtenay’s suit was also promoted by his mother, Gertrude Blount, one of Mary’s closest friends and by many of the men who had been her most faithful supporters during Edward’s reign.

Mary, however, considered him completely unsuitable – he was too young, a subject with no lands or power of his own, and was, not surprisingly, given his long-term incarceration, immature and lacking in judgement. When pressed, Mary snapped at her Chancellor that his friendship for the man was not a good reason for her to marry a subject. It is not hard to imagine that a marriage to Courtenay might well have created the problems later caused by the marriage of Mary’s cousin, the Queen of Scots to the aforementioned Lord Darnley, who had some of the same characteristics.

Reginald Pole had been suggested as a husband for Mary some seventeen years before, by the rebels of the Pilgrimage of Grace, much to her father’s chagrin. He had been in exile since the early 1530s, and although not an ordained priest in 1553, he was a Cardinal and a scholar. He was also still a subject of the Queen, and had nothing to bring to a marriage, other than his Plantagenet blood. In any event, Mary had other ideas for his future – leadership of the Church in England.

That left a foreign match. But whom could she choose? The French King, Henri II, to whom she had once been betrothed, was already married, and his sons were children – the oldest, only nine, was also contracted to Mary, Queen of Scots. There was Erik, the Prince of Sweden, only twenty, and a Lutheran, so not a good prospect. Another potential candidate was Dom Luis of Portugal, who had been suggested as a spouse for Mary several times in the past. He was her first cousin, and ten years her senior. He might have proved a good choice – not a King at home, so more able to spend time in England and old enough, presumably, to have maturity and judgement.

There were also Ferdinand of Austria (later Holy Roman Emperor) another cousin, who had been widowed since 1548 and Ferdinand’s son of the same name who was unmarried and of suitable age. As the elder Ferdinand had more than enough children (thirteen who lived to adulthood) and was constantly occupied in war with the Sultan of Turkey, and helping his brother, Emperor Charles V, with maintaining Hapsburg dominance, he would have had little incentive to marry again. His second son, although only 24, was a definite possibility, and Ferdinand senior wrote to Charles requesting the latter to stop trying to prevent the match.

There was the widowed Emperor Charles himself, and his widowed son, Philip. Mary would originally have preferred the father – she had fond childhood memories of Charles and believed that he had supported her throughout her life. With the benefit of the availability of his correspondence with his ambassadors which Mary never saw, we can see that his support of Mary was qualified, and never allowed to interfere with his own duties or ambitions, but for her, it had been a life-line.

Charles wanted Mary to marry Philip, and given that Mary believed that Charles had always had her best interests at heart, she was willing to accept his advice. Philip himself was distinctly unenthusiastic, although he accepted his father’s decision obediently. He had a long-term mistress, and was negotiating for a marriage with yet another cousin, an Infanta of Portugal, like his first wife.

Historically, friendship, if not formal alliance, with the Low Countries had been a plank of English Kings’ foreign policy. The Low Countries were England’s biggest trading partner and any breach was economically disastrous. Castile, too, had been an ally for centuries, providing a queen for Edward I, and a king as husband for John of Gaunt’s daughter, Katherine of Lancaster. Alliance with the countries of the Iberian peninsula was considered an important tool in the on-going pursuit of the French Crown.The Spanish alliance represented by the marriage of Katharine of Aragon, first to Arthur, Prince of Wales, and then to Henry VIII, had been widely popular. Considering this history, Mary’s policy of marrying Philip, who was not just King of Spain but also the ruler of the Low Countries, seemed to be an obvious decision.

Unfortunately, public perceptions of this foundered again on the rock of Mary’s gender. It is impossible to imagine that, had Edward VI lived and chosen to marry a Spanish princess, that anyone would have dreamed of questioning his choice. It was the assumption that Philip would not just be Mary’s consort, but that he would become King and subject England to Spanish rule that worried people.

Times had changed, too, since the marriage of Henry and Katharine. The concept of the nation-state was beginning to form. The development of the Reformation and growing populations across Europe were creating a much stronger perception of nations as fixed entities, rather than fluid inheritances of kings. The English had always been hostile to ‘foreigners’ – there are numerous mediaeval reports of riots against perceived interlopers in London, and whilst creating international alliance was clearly the job of the monarch, the fear of domination was real and the heavy-handed rule of Charles and Philip in the Low Countries caused unease. It was this marriage that was the criticism most widely made of Mary during her life-time, and during Elizabeth’s reign, when Spain came to be seen as the enemy.

Mary’s Council was divided. Gardiner, in particular, urged her to marry Courtenay, Then the Commons, led by Speaker Sir John Pollock, brought a petition to her, to marry, but not to a foreigner.

Mary reacted with all the fury of a thwarted Tudor, not even following etiquette by allowing Gardiner to reply for her. She leapt to her feet, having been obliged to sit by the lengthiness of Pollock’s address and began. She was very grateful, of course, to Parliament for its advice to marry but she thought their second point ‘very strange’.

‘Parliament,’ she said, ‘was not accustomed to use such language to the Kings of England, nor was it suitable or respectful that they should do so. Even Kings in their minority had not been interfered with in the matter of marriage. Having made her point that she would brook no interference in her choice of husband, Mary then caressed them with words of love, assuring them she thought of nothing but the welfare of the kingdom as a good ‘princess and mistress’ should do. This was certainly true – the question was whether she was right in her interpretation of the good of the realm.

Not everyone was convinced that Mary’s decision to marry a Spaniard was the right one, and rebellion followed – certainly fomented by Henri II of France, who was nervous of any alliance between England and Spain, but with fairly widespread support for the fundamental point that Mary should not marry Philip.

The Tudors were not the seventeenth century Stuarts – they knew very well, in practical terms, that they ruled by the consent of the people, rather than by Divine Right, but they would resist encroachment on their prerogatives to the utmost, before they would pretend to give in, with a show of charm and love, prior to doing exactly what they wanted. It was a trick that Henry VIII had used with the Pilgrimage of Grace, and that Elizabeth would use frequently.

Mary, too, knew all about courting public opinion and, whilst her Council were urging her to flee London in the face of the oncoming rebels, led by Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger (son of the poet) she rode into London to make a speech at the Guildhall.In it, she promised that whilst she was convinced of the merits of the proposed match, she would not continue with it without Parliament’s consent. Even those who were opposed to her policies, admitted that Mary’s speech carried the crowd and she departed in triumph.

Wyatt dispatched, Parliament accepted the treaty as drafted – in every respect, it was favourable to England. Philip had no sovereign power, or right to make political appointments, could not involve England in the Hapsburg-Valois wars, could not take Mary out of the country, and any child was to inherit both England and the Low Countries, which would have been a great gain. Nevertheless, Mary was the only one who was really pleased with the deal struck.

This article is part of a Profile on Mary I available in paperback and kindle format from Amazon.