1485 Battle of Bosworth

Chapter 6 : Lead Up to Battle

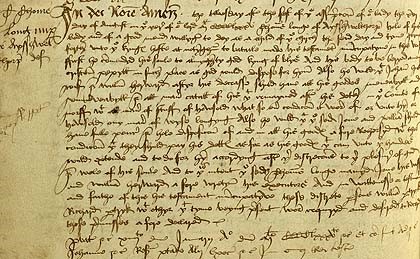

Richard was informed of Henry’s positive reception at Lichfield. It is not clear why he had not advanced to meet the invaders before – if Henry gained the Roman road, ahead of the royal army, he could arrive in London before Richard could catch him. His delay may be attributable to concerns that he did not yet have his full force. He sent out more requests for men, including one to Henry Vernon of Haddon, Derbyshire, one of his esquires of the body, and presumably to others. Vernon is not known to have been present at the battle, and it has been inferred that he failed to respond to Richard’s order.

It seems that Vernon was not the only one to be dilatory in response. The city of York, rather than sending the 400 men requested, dispatched only 80, and they were so late in receiving the summons it is very unlikely that they reached the muster point in time. Exeter is recorded as dispatching 16 men, but there is no evidence of any other towns providing Richard with troops. London gathered a very large force – well over 3,000 but they were kept to protect the city itself, and not sent to support either contender.

It has been estimated, that out of a peerage of forty, only seven nobles definitely attended at Bosworth in Richard’s army – John Howard, Duke of Norfolk and his son, Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey; John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, who was Richard’s nephew and probably heir given that Richard’s only legitimate son had died the year before; Francis, Viscount Lovell; John, Baron Zouche of Harringworth and Sir Walter Devereux, Baron Ferrers of Chartley, whose sister, Anne, Countess of Pembroke’s husband had been Henry Tudor’s guardian and whose nephew, the Earl of Huntingdon, was married to Richard’s illegitimate daughter.

Additional nobles who might have been present include Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmoreland, George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury and the Lords Audley, Grey of Codnor, Scrope of Bolton and Scrope of Masham. Interestingly, in accounts of the rescue of Surrey from the battlefield, by Shrewsbury’s uncle, Gilbert Talbot, the implication is that the Talbots supported Henry.

Richard set out for Leicester, forty miles (about 64km) south of Nottingham and a similar distance east of Lichfield, where he met the Duke of Norfolk and his men. He was also joined by his Constable of the Tower of London, Sir Richard Brackenbury, who was ordered to bring with him Sir Walter Hungerford and Thomas Bourchier, who had been imprisoned for their part in Buckingham’s rebellion. Whether Brackenbury was half-hearted or incompetent is unknown, but his prisoners managed to escape and join Henry.

More men continued to join the invading army and Henry moved on to Tamworth, actually on Watling Street, arriving on 20th August. It was the following day that Henry finally met his step-father, Thomas Stanley, with, according to the chronicler Hall ‘diverse congratulations and many friendly embracings’ in the abbey at Merevale, near the town of Atherstone, where he probably encamped.

The exact number of men on either side, as for any other mediaeval battle, is hotly disputed. The arguments presented in Bosworth 1485: Reconstruction of a Battle (G Foard & A Curry), are very convincing, and we follow that in suggesting that Henry, beginning with 2,000, had some 5,000 by the time he reached the field, and that the Stanleys’ had a further 1,000 – 1,500 – rather less than often suggested.

Richard’s force is put, by the same authors, as around 7,000 – 8,000, although, it will appear, not all engaged. Overall, the armies were not dissimilar in size (if the Stanleys are factored in with Henry), with a mixture of trained and untrained troops (although Henry possibly had more trained soldiers from his French and Scots recruits). In addition, Henry’s men had been together for nearly three weeks – they will have melded into a more coherent unit, and, perhaps, built up some fitness. The vast majority on both sides would have been on foot.

Richard left Nottingham for Leicester, on either 19th or 20th August where he remained, according to tradition at the Blue Boar inn, before departing on the morning of 21 st

Where Richard camped that night is not certain – Ambion Hill was given as the location for many years, and apparently is still considered a possibility.

It is apparent that by this date both sides knew where and when the battle would take place – according to Foard & Curry, agreement before-hand on a time and location via heralds was reasonably commonplace. This makes sense in an era before swift communication, and in which the set-piece battle was the main tactic.