Following the Tudors in Exile

by Tony Riches

In late August 1471 Jasper Tudor escaped the Yorkist siege of Pembroke Castle with his fourteen-year-old nephew Henry, the future King Henry VII. Although Jasper owned a house in the nearby coastal town of Tenby, he knew the community could be full of York’s spies. Capture could mean execution as ‘rebels’ or incarceration in the Tower of London, so they sought refuge in the house of Jasper’s friend and neighbour, the Mayor of Tenby, Thomas White.

This where my journey to follow in their footsteps began. The original house has now been replaced by a chemist’s shop but the tombs of Thomas and his son John White can be seen in medieval St Mary’s Church, directly across the road, which would have been frequented by Jasper Tudor.

Local legend claims Jasper and Henry escaped their pursuers by hiding in Thomas White’s cellar before making their way to the harbour through secret tunnels. The manager of the chemist’s shop allowed me to visit the extensive cellar of the original house, now used for storing medicines, and showed me the entrance to the tunnel.

Armed with a torch, I explored the extent of the tunnel deep under the streets of Tenby. I found a medieval fireplace and could see it would be possible for the Tudors to hide there while waiting for a ship. It was possible to walk in their footsteps for some distance but the access to the harbour had been bricked up some time in the past. There was also a tunnel leading into the crypt of the church, which would have provided them another escape route.

I’ve sailed from Tenby harbour many times, including at night, so have a good understanding of how Jasper and Henry might have felt as they slipped away to the relative safety of Brittany. Rather than follow their course around Land’s End, I chose to sail on the car ferry from Portsmouth to St Malo in Brittany, where I began to retrace the Tudor’s time in exile.

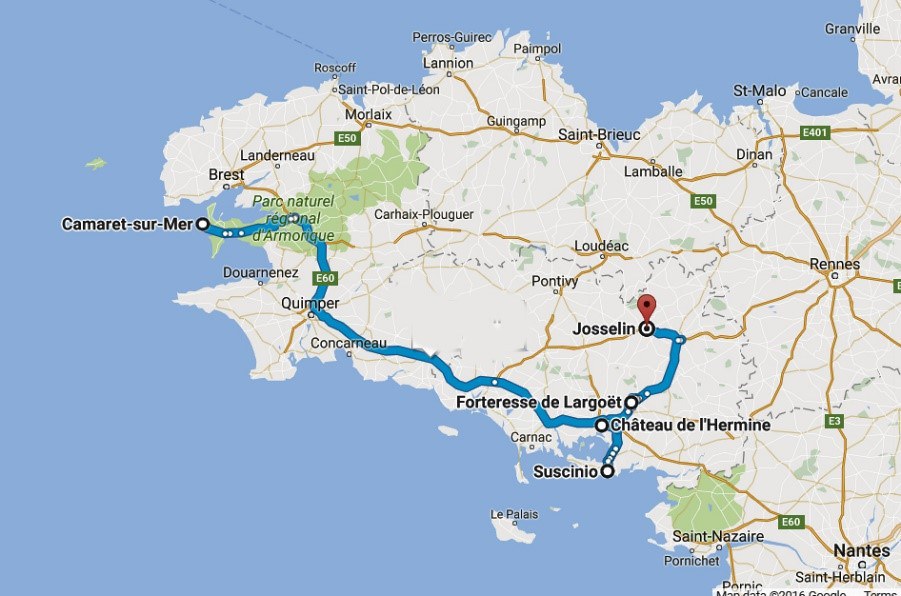

I’ve read that little happened during those fourteen years but of course Brittany was where Henry would come of age and Jasper would help him plan their return. There is a story they were forced to shelter at the island of Jersey before their long and risky sea voyage saw them land at the tranquil Breton fishing port of le Conquet, near Camaret, in September 1471.

They travelled to the residence of Duke Francis of Brittany, at Château de l’Hermine in Vannes, and requested his protection. Duke Francis would have immediately appreciated the political value of the exiled Tudors to King Edward IV, as well as to King Louis of France, to whom they were related through the Valois family of Jasper’s mother, Henry’s grandmother, Queen Catherine.

It seems the Duke was soon visited by York’s envoys, who tried, unsuccessfully, to negotiate their return. Encouraged by King Louis, Duke Francis had promised to ensure their safety as his guests while they remained ‘within his dominion’. Although they effectively became his prisoners, it is said Duke Francis treated the Tudors as his own brothers, with ‘honour, courtesy and favour.’

It was a wet day in Vannes as I went in search of the Château de l’Hermine. I knew that little of the original 14th century palace remained, as the ruins were redeveloped as a hotel in 1785, although the original city walls remain. There is a free car park near the harbour, a short walk from the old city and the Château de l’Hermine, which has grand public gardens fronting the main road to the port. Although there was little point in entering the château, it was interesting to explore the ancient walls and the narrow maze of streets.

The Tudors are recorded as spending a year in Vannes as the Duke’s guests, during which time they would have learned a great deal about the politics of Brittany, France and Burgundy. King Edward IV offered a substantial reward for the capture of Henry Tudor, despite Duke Francis having given him his word that he would guard Henry and Jasper and prevent their return to England.

The Duke sent back their English servants and replaced them with his own, then in October, 1472, he was so concerned they might be abducted by York’s agents he moved Jasper and Henry from the city to his remote ‘hunting lodge’ by the sea south of Vannes – the next stop on my own journey. I followed the Tudors to the Château de Suscinio on the coast. I found it has been restored to look much as it might have when Jasper and Henry were there, and the surrounding countryside and coastline is largely unchanged.

When Yorkist agents began plotting to capture the Tudors, Duke Francis moved Jasper and Henry to different fortresses further inland. I stayed by the river within sight of the magnificent Château de Josselin, where Jasper was effectively held prisoner. Although the inside has been updated over the years, the tower where Jasper lived survives and I was able to identify Tudor period houses in the medieval town which he would have seen from his window.

Henry’s château was harder to find but worth the effort. The Forteresse de Largoët is deep in the forest, outside of the town of Elven. His custodian, Marshall of Brittany, Jean IV, Lord of Rieux and Rochefort, had two sons of similar age to Henry and it is thought they continued their education together. Proof I was at the right place was in the useful leaflet in English which confirmed that: ‘On the second floor of the Dungeon Tower and to the left is found a small vaulted room where the Count of Richemont was imprisoned for 18 months (1474-1475).’

Entering the Dungeon Tower through a dark corridor, I regretted not bringing a torch, as the high stairway is lit only by the small window openings. Interestingly, the lower level is octagonal, with the second hexagonal and the rest square. Cautiously feeling my way up the staircase I was walking in the footsteps of the young Henry Tudor, who would also have steadied himself by placing his hand against the cold stone walls, nearly five and a half centuries before. (Although it was called the ‘dungeon tower’, in subsequent research I discovered intriguing details at the National Library of Wales which suggest Henry Tudor enjoyed more freedom at this time than is generally imagined. The papers claim that, ‘by a Breton lady’, Henry Tudor fathered a son, Roland Velville, whom he knighted after coming to the throne.)

On my return to Wales I made the journey to remote Mill Bay, where Henry and Jasper landed with their small invasion fleet. A bronze plaque records the event and it was easy to imagine how they might have felt as they began the long march to confront King Richard at Bosworth.