Oxburgh Hall

A moated manor house

Chapter 2 : House and Gardens

Leaving the car park, ahead of you is the great brick wall which surrounds the estate, with regular towers built into it, although these date from the early nineteenth century rebuilding or rather “re-edifying" under 6th Baron Bedingfield. There is a small orchard with rare species of apple and pears and a pleasing herbaceous border directly to the left. Closer to the house, there is a formal Victorian-style bedding scheme, but one's eye is drawn inexorably to the house; sitting tranquil, timeless, self-contained, in its moat, water lilies clustering at the corners.

Entrance

to the house is over a single-track brick-built bridge of three arches. The bridge leads through the four-storey gatehouse,

built as a pair of octagonal towers. The

battlements again are reconstructions and some of the windows are later

additions, but the overall effect is impressive.

Passing

under the gatehouse, and by-passing the old gun room (now doing duty as a

second-hand bookshop) you enter a completely enclosed courtyard. There is a small

shop, selling National Trust books and souvenirs and overlooking the moat, a

sizeable café, which provides sandwiches, soups and cake, although the ordering

system is bizarre, and the sandwiches, depressingly, are made with margarine.

The tour

begins in the West Corridor. Everywhere

are mementoes of the Bedingfield family, who, rising from gentry status in the

Tudor period, climbed the ranks under the Stuarts, despite remaining committed

Catholics. An astonishing number of

Bedingfield women escaped to Europe in the days of the Penal Laws to become

nuns, but the family clung on, despite heavy losses.

The first

room is a dark red Saloon lined with portraits of monarchs from the 17th and

18th centuries. Across a staircase hall is

the Library, lined with the usual acres of unread books in smart bindings, and

a scattering of well-thumbed novels. There is an impressive fireplace, and

beautiful wall paper dating from the remodelling of the house in the 1830s. This room

takes the majority of the south wall. At

the east end, is the Dining-room with an enormous Jacobean buffet and some

delicate Delft Porcelain. Over the

fireplace is a portrait of Sir Henry Bedingfield (1511 – 1583).

Travelling along the East corridor, it would be easy to miss one of the most important rooms in the house: the small antechamber in which are housed the sumptuous embroideries worked by Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury (Bess of Hardwick) during Queen Mary's long captivity in the custody of Bess' husband.

The

embroideries are huge - at least 6ft in length and four in breadth. The backgrounds are green silk with delicate

criss-cross lines, interspersed with raised pictures of strange and exotic

animals, derived from a sixteenth century bestiary. There is a useful video description of the

history of the needlework.

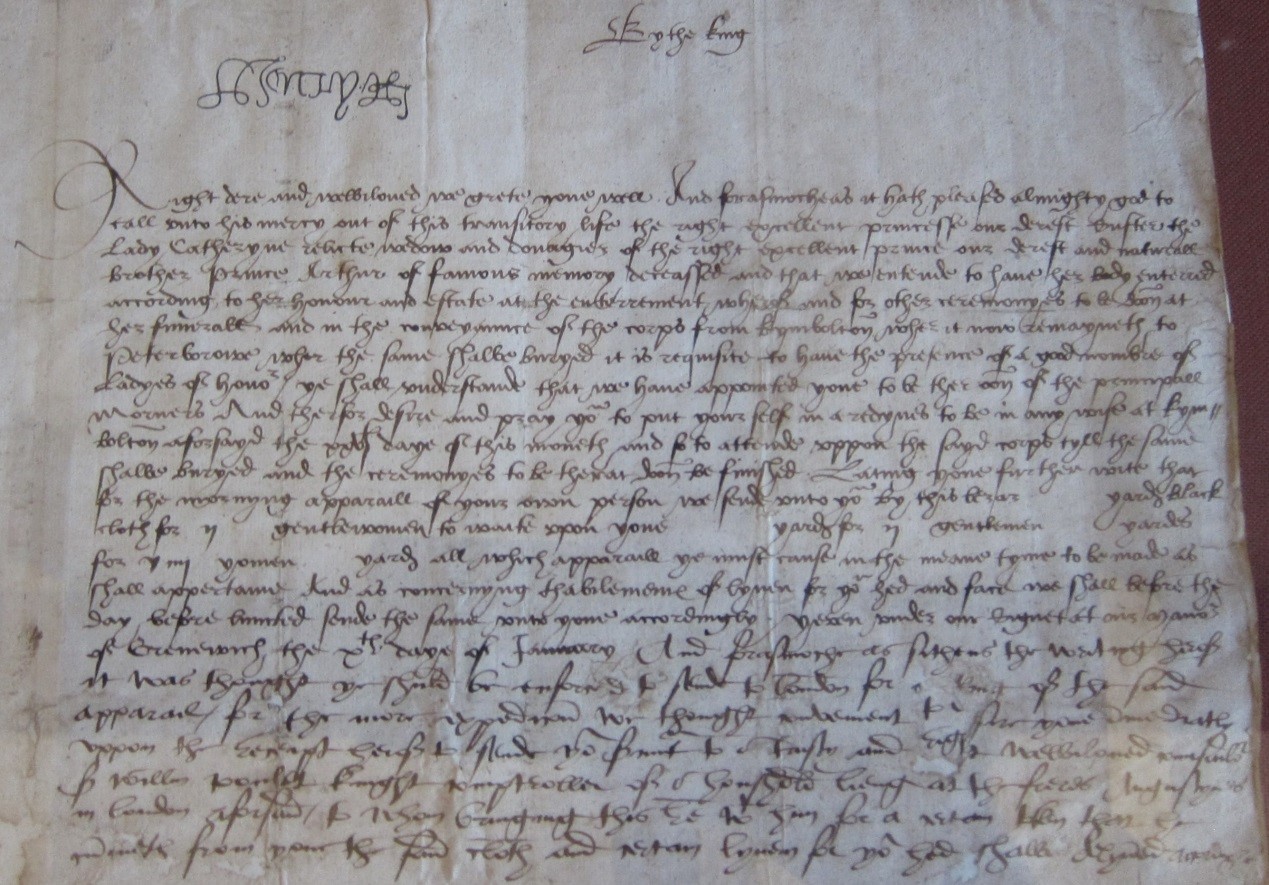

Climbing a short staircase, you enter the room known as the King's Chamber. This is a large, light space with an impressive fireplace, a beautiful extent of linen fold panelling, and a selection of letters and seals. Particularly interesting are two letters from Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. The former is an instruction to Lady Bedingfield to attend the corpse of Queen Katharine of Aragon (referred to in the letter as the Princess Dowager, late wife of the King's brother, Prince Arthur) on its final journey to interment at Peterborough Cathedral. Lady Bedingfield's husband, Sir Edmund, had been Queen Katharine's gaoler at Kimbolton, and the instruction from the King ordered her to attend and provided material for mourning dress for herself and her attendants.

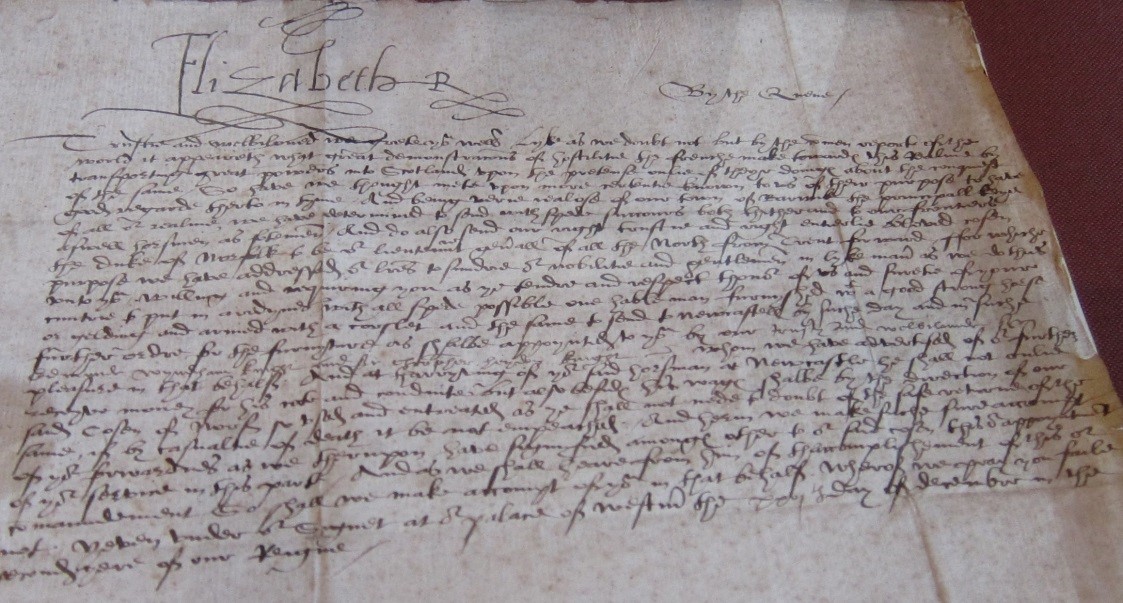

The letter from Elizabeth I has her well-known flourish of curlicues at the top. It is addressed to Sir Henry Bedingfield, requiring him to send a mounted man for the defence of Berwick who will:

will “be so used and entreated as you shalle not nede to doubte of the safe returne of the same if the casualitie of death it be not empeached.”

Next is an

anteroom, leading into what was once the guarderobe (privy), positioned

carefully over the moat. But the room

houses something else - a priest hole, designed by the genius Nicholas Owen. A small portion of the floor lifts, revealing

a drop of a couple of feet, and a space some 7 ft high, and about 3ft in

breadth and width. It is easy enough to

climb in, but a bit more difficult to get out.

You can imagine being sealed in, with no knowledge of whether the pursuivants

had entered the hall, searched, and left, or were lying in wait ready to pounce

as soon as you crept out. A desire to

escape soon sweeps over you and you are relieved to continue the tour up a

spiral staircase to the Queen's room.

The walls are lined with two seventeenth century tapestries, originally

commissioned by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, but not paid for prior to

his assassination in 1628 and hence sold off cheap.

There are

models of a man and woman in costume dating to about 1515. It is interesting to see how the English or gable

hood was designed, the gable shape being created from a stiffened piece of

velvet, sewn to the front, and standing proud of the velvet hanging down the

back. From the

top of the tower a splendid view over the surrounding countryside is afforded. All the way down the spiral stair, the exit

is back on the bridge, opposite the gun room. In the

gardens, about 300 yards from the Hall, is the family chapel, built in 1836 as

a Catholic chapel for the family, able at last to worship as they pleased

following the final lifting of the Penal Laws.

Depending on weather, visitors can follow a path through the estate woodland.

Leaving the Hall, the partially ruined village church beckons. The tower collapsed in 1948 and the church is now confined to the chancel, with a huge west window. Fortunately, the Bedingfield chantry remains, with an astonishing terracotta screen, dating from the 1530s which would seem more in keeping with a Southern Italian palazzo than an English country church.