William Cecil: Life Story

Elizabeth I’s Chief Councillor

Chapter 9 : The Succession

The issue that consumed a vast proportion of Cecil’s time in the 1560s was that perennial Tudor favourite, the succession. In accordance with the powers granted in the 1544 Act of Succession, in his Will, Henry VIII had nominated the heirs of the Lady Frances to succeed. With her eldest daughter, Lady Jane Grey, now dead, this right devolved on her second daughter, Lady Katherine Grey.

Although there can be no doubt whatsoever that Cecil wanted Elizabeth as Queen, and for her to marry and bear an heir, he was quite content with the notion of Lady Katherine as a successor. She was a family connection, and presumably a Protestant, although she had never been as ardent as her sister and had cheerfully conformed under Mary.

Mary had treated the Greys kindly, but had made it pretty clear that her personal choice, lacking an heir of her body, would be another cousin, Lady Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, a good Catholic, with a son.

Elizabeth cordially disliked the Grey sisters, and demoted Lady Katherine from her position in the Privy Chamber. She disliked Lady Lennox even more, but was content to play her various cousins off against each other. Elizabeth abhorred any mention of the topic and never, in all her long life made an unambiguous statement about it, but we can infer from some of her comments, that she believed her legitimate heir was Mary of Scotland, a view probably shared at the beginning of her reign with her largely Catholic nobles, none of whom wanted interference with the usual laws of inheritance.

For Cecil and the Protestants, however, the idea of Mary of Scotland as queen was their worst nightmare. All of their energies therefore went into persuading Elizabeth herself to marry as soon as possible. Writing to Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, England’s Ambassador to France, Cecil said:

‘God send our mistress a husband and by him a son, that we may have a masculine succession.’

Elizabeth never rejected the concept totally. Whilst we can look back and consider that her eventual non-marriage worked well, it is not clear that that was a conscious decision by the Queen herself. It was more that the right candidate never appeared. The princes of Europe were generally Catholic, and the example of the trouble caused by her predecessor’s choice of a foreign king didn't seem to make that a good idea.

But marriage to one of her own subjects was also fraught with difficulty. The Scottish Earl of Arran, heir in 1560 to Mary, Queen of Scots until she remarried and had a child, suggested his own son, but Elizabeth didn't care much for that idea – fortunately, as the gentleman in question went mad in 1562 and spent the rest of his life in confinement.

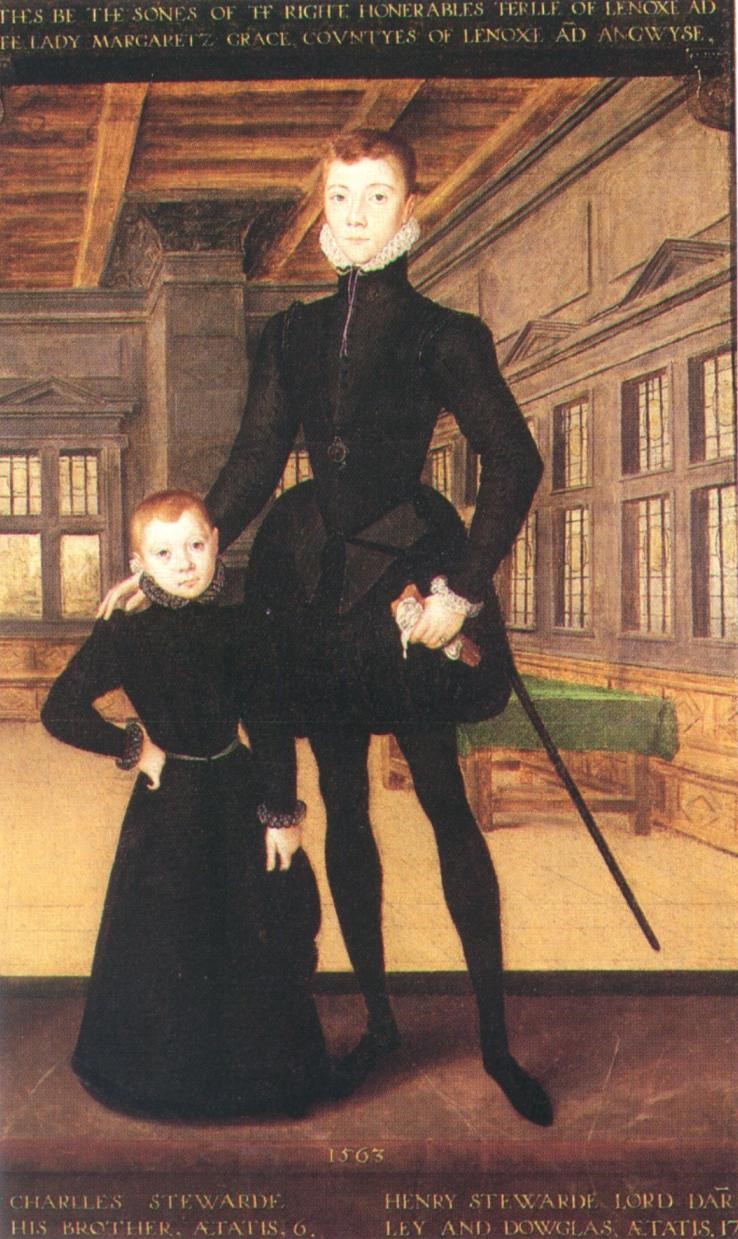

Elizabeth’s own closest male heir was the young Lord Darnley, son of Lady Lennox, but in 1560 he was only fourteen.The next male heir was, Henry Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon, descendant of both the Duke of Buckingham, executed in 1521, and Margaret, Countess of Salisbury, executed in 1541. He was Protestant, even Puritan, but he was already married to Katherine Dudley, daughter of the late Duke of Northumberland.

Cecil and the Privy Council sought out candidates everywhere, but they were hampered not just by the lack of choice but by Elizabeth’s own feelings. During the early 1560s it was apparent to every on-looker that Elizabeth was deeply in love with her Master of Horse, Lord Robert Dudley. He was constantly at her side. They danced, hunted, gambled and laughed together.

Fortunately, from the perspective of Cecil, Dudley was not free to marry. His long-suffering wife was stuck in the country whilst Lord Robert sat up till all hours flirting with the Queen. Nevertheless, Cecil was horrified by the Queen’s imprudent behaviour and pleaded with her to moderate her public conduct, especially when foreign rulers, who were still considering marriage treaties, began to suspect that the Queen was sleeping with Dudley – a charge she always denied.

Matters came to a head in September 1560 when Cecil told the Spanish Ambassador that he was so appalled by Elizabeth’s behaviour that he was planning to resign, especially, said Cecil, as Elizabeth and Dudley were planning to kill Lady Dudley. It seems quite astonishing that the cautious Cecil would have said such a thing to a foreign ambassador, had he not had an ulterior motive, particularly as, within days, Lady Dudley was indeed dead in suspicious circumstances.

Whatever Cecil’s motivation for his bizarre comments, the result of events was that Elizabeth could never marry a man whose wife was rumoured to have been murdered – that threat, at least, was over, although Dudley did not cease to hope for another fifteen years.

But, as if Elizabeth’s headstrong behaviour were not enough, Cecil’s own preferred candidate for her successor, Lady Katherine Grey, had called forth the Queen’s wrath by a secret marriage and pregnancy. Cecil was quite unable to deflect Elizabeth’s rage from the offending girl, who was sent to the Tower.

In 1563, the House of Commons, at the suggestion of the Privy Council, brought forth a petition to the Queen, requesting her to name her successor. Elizabeth listened politely, then, saying it was an important matter, which required much thought, agreed to consider the request. The Lords then followed suit, receiving the same answer. This was not good enough for Cecil, who drafted articles for a bill to deal with the disaster of Elizabeth’s death. Instead of the Crown passing automatically to her heir (whether that were considered to be Mary of Scotland or Lady Katherine Grey), regal authority would pass to a Privy Council of twenty-four until such time as Parliament selected an appropriate, Protestant, monarch.

Not surprisingly, this draft bill failed to receive any support from Elizabeth. She would not be forced by Parliament, the Privy Council, Cecil or anyone else to derogate from the principle that monarchs rule by God-given right, not through appointment by Parliament.

Cecil’s efforts to persuade Elizabeth to name a successor rumbled on, without success, at least until after the death of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1587. By then, her obvious heir was Mary’s son, James, who, as a Protestant, would be able to fulfil Cecil’s dream of a single, British, Protestant state, although Cecil never lived to see it.