William Cecil: Life Story

Elizabeth I’s Chief Councillor

Chapter 5 : The 1553 Succession Crisis

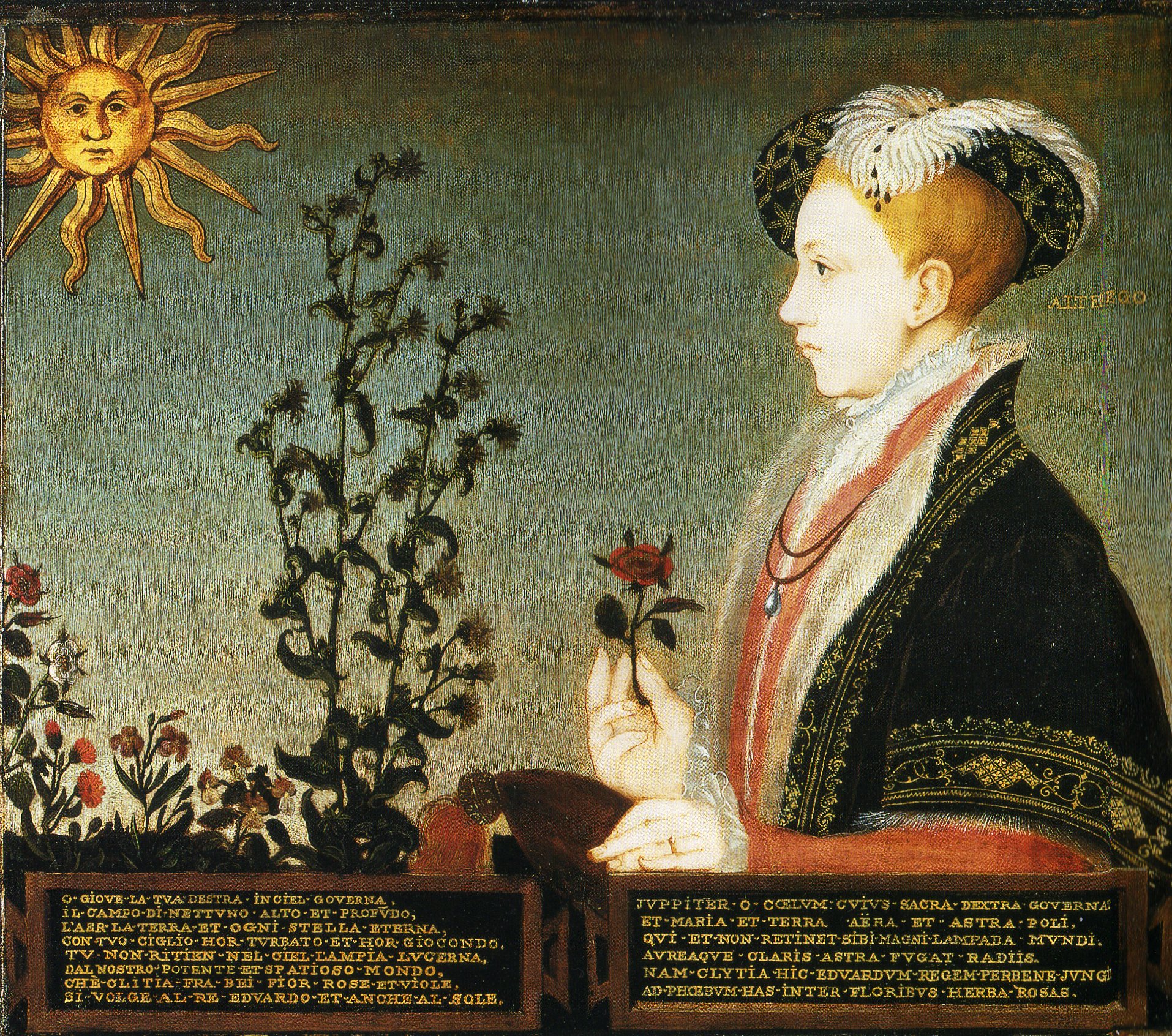

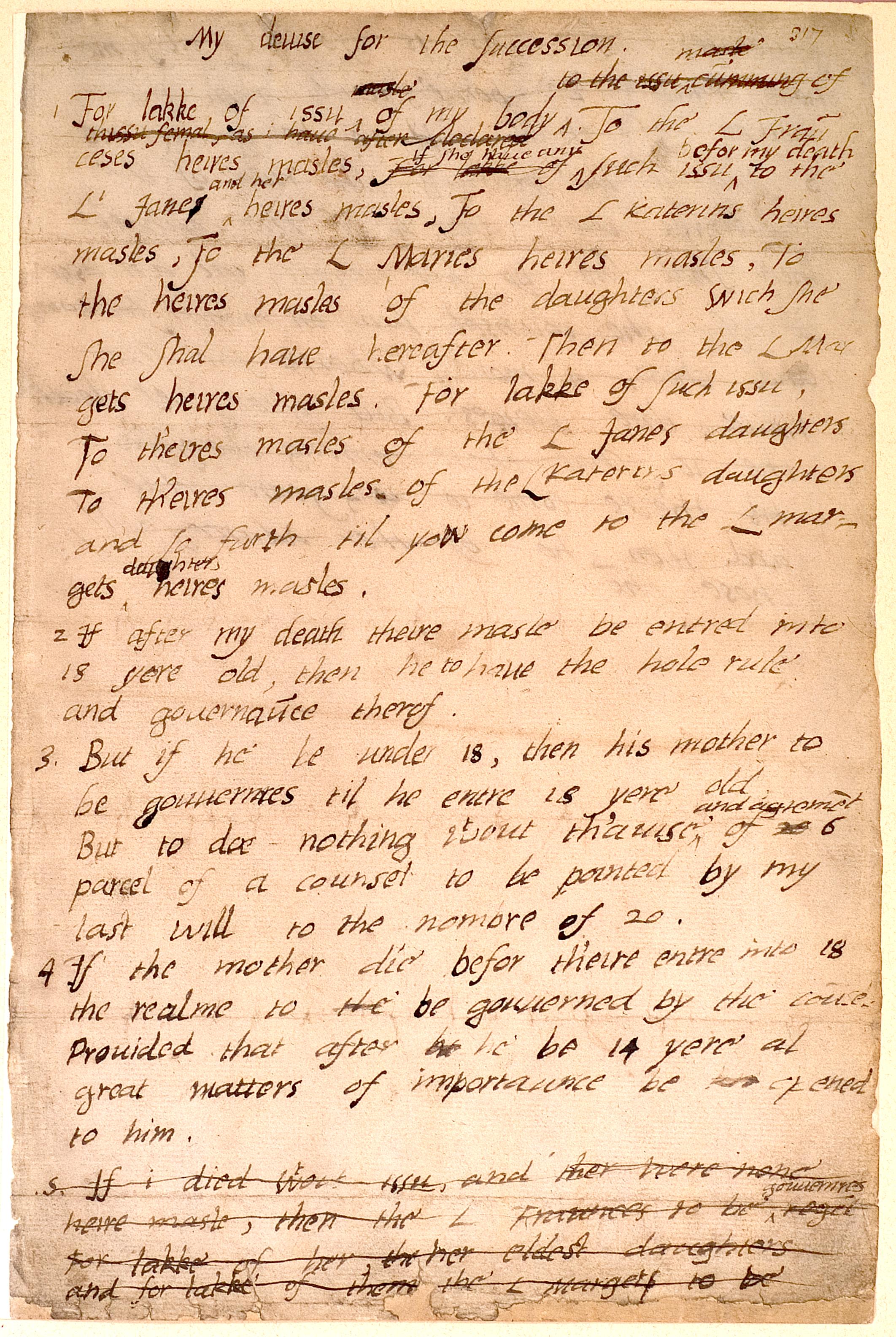

In early 1553, Edward VI drew up a ‘Devise for the Succession ’ which attempted to overturn the Act of Succession 1544 (see Chapter 2). The King’s initial plan had been to find a male, Protestant, successor (overlooking the male, Catholic Lord Darnley, and his own half-sisters). But by June, Edward’s time was running out and there was no time for more boys to be born. He settled the succession on his evangelically Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey.

The level to which Edward was influenced by Northumberland has been a matter of some debate. There can be little doubt that Edward wanted to preserve his Protestant reformation, and that he would prefer to be succeeded by Lady Jane than by his sister Mary. Equally, Northumberland would benefit as he was Lady Jane’s father-in-law.

Cecil’s level of involvement is also difficult to pin down precisely. We might infer that he would have preferred the Crown to pass to Jane – they were of similar mind in religious matters. There was also a family connection – Jane’s cousin, Frances Grey of Pirgo, was married to Cecil’s brother-in-law, William Cooke. That may seem a rather distant connection today, but, in the sixteenth century, the extended family was an important network of influence.

There is no evidence of Cecil’s state of mind, and the detailed record of his actions is contained in exculpatory letters he sent to Queen Mary after the event, so we might suppose he gave himself the benefit of the doubt when telling her his story.

In spring of 1553, Cecil was absent from court – his father had died, and he himself had taken to his bed with an illness that lasted for nearly two months. On his return in May he discovered that the King had no hope of surviving the summer and that there was a plan to subvert the succession. He avoided Privy Council meetings, so as not to be involved. Fearing trouble, he arranged for his money and valuables to be hidden.

On 11th June, he was obliged to attend a Council meeting, at which Lord Chief Justice Montague had been invited by the Privy Councillors (including Cecil himself) to attend to give evidence as to the legality of changing the succession without an Act of Parliament. King Edward told Montague he wanted his ‘Devise’ implemented, but Montague informed King and Council that to implement it would be treason, as defined by the Act. The King’s personal Devise could not trump an Act of Parliament. This was never going to be music to a Tudor king’s ears – even one so young as Edward. Montague was ordered to do as he was told and draw the Devise into legal form. He resisted as long as he could, trying to persuade Edward to call Parliament to make the changes required.

The King was not willing to wait, so, bullied and threatened with dire consequences by King and Council, Montague drew up the document, first requesting a pardon under the Great Seal. In the background, Cecil shared his misgivings with some of his friends and family – including his wife’s brother-in-law, Nicholas Bacon. Bacon’s wife, Anne Cooke, was a close friend of the Lady Mary’s, so it was politic to get his doubts into the right ears.

Once the legal document was drawn up, Cecil, like all the others, added his signature. He claimed however, that he signed only as a witness of the King’s intention. No doubt he, like all of his colleagues, was praying for the King to live long enough for the Parliament that had been summoned to relieve him of the taint of treason which clung about them all.

Edward, however, did not live long enough. He died on 6th July 1553, and Cecil was now faced with the choice of committing active treason by supporting Lady Jane, or not. Jane’s new Privy Council wrote an offensive letter to Mary, pointing out that as she was illegitimate she could not inherit. Cecil, although he declined to write the offending missive, signed it. He also avoided writing any other letters that were blatantly treasonable, such as orders to the Lords Lieutenant of the counties, or Jane’s Accession Proclamation. He did, however, take the oath of fealty to Jane.

Cecil then began (or so he later claimed) to actively undermine Jane’s authority. He sounded out his fellow Secretary, Sir William Petre, the Earls of Winchester, Bedford and Arundel and Lord Darcy, with a view to handing over Windsor Castle to Mary. Whether this counter-coup was real, or would have been successful, became, in the end, a moot point. Mary was victorious, and by early August was on her way to London to claim her Crown, and to meet a Privy Council, including Cecil, that had suddenly discovered that it had supported her all along.

Cecil raced to meet her, sending his servant, Robert Alford, in advance, and travelling with Nicholas Bacon. He also composed a detailed defence of his actions. He finally came into Mary’s presence on 31 st July at Ingatestone Hall.

Whether Mary believed his protestations is debatable. However, her policy from the beginning was to accept all of the grovelling from the Councillors, and let them pin all of the blame on Northumberland and his two closest allies.

Cecil’s last act as Secretary to Edward VI was to march in his funeral procession on 8th August, 1553.