The Four Marys

Companions to Mary, Queen of Scots

Chapter 3 : Centre of the Scottish Court 1561-1568

Following her brief period as Queen of France, the widowed Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, aged eighteen, and ready to take up the burden of personal sovereignty. Her Marys returned with her as ladies-in-waiting. The first years in Scotland were taken up with Mary’s determination to control the complex political situation she was faced with.

A group of nobles, led by James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, Mary’s half-brother, and calling themselves the Lords of the Congregation, had converted (some with rather more sincerity than others) to Protestantism and changed the official religion of Scotland, leading them to look for support from Protestant England, rather than Catholic France. Mary, no religious fanatic, tried to steer a course between the different factions which sought to dominate her. When not engaged in state business, the Queen recreated some of the splendour of the Court of France, and in this she was ably assisted by her Marys.

The four Marys went everywhere with the Queen, even accompanying her to Parliament in 1563. They had stools in her chamber, when to sit in the presence of the monarch was an extraordinary honour; they waited on her at table and they took leading roles in the lavish court entertainments so important to sixteenth century monarchy. They danced at masques, played music for visiting ambassadors, rode, hunted and hawked with the Queen and her nobles. More informally, they joined Mary in dressing up as burgesses’ wives to walk around Edinburgh and St Andrew’s, shopping in the market and cooking, in a faint foreshadowing of another doomed Queen, Marie Antoinette. They even donned male costume, on one occasion at a banquet for the French Ambassador, as well as for practical reasons when hunting, outraging the sensibilities of the increasingly dominant religious radicals.

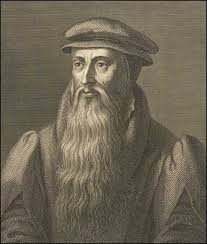

Mary was unfortunate in that her greatest enemy at home was John Knox. Knox, a militant Calvinist, was even more misogynistic than most men of the age, and spent a good deal of time inveighing against female rule in such delightful tomes as

“The first blast of the trumpet against the monstrous regiment of women”

and haranguing Mary in both public and private. Knox made the most of every innocent pastime derived from youth and high spirits at the Queen’s court to insinuate that the Queen and her entourage, including the Marys, lived immoral lives.

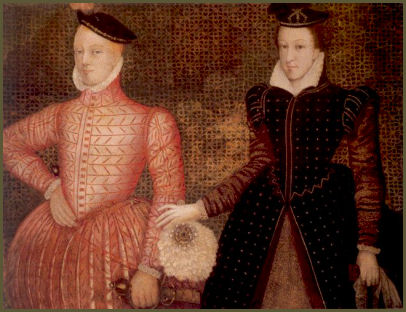

Pressure mounted for the Queen to remarry – there were many at home and abroad who had their eyes on the Crown – and even Mary’s person. In a frightening incident a foolish young poet, Chastelard, was found hiding under the royal bed. Mary, too nervous to sleep alone thereafter, took Fleming as her “bedfellow.” The Queen’s affection for her Marys was one argument used to persuade her to take a husband, as they had all vowed to remain single whilst she did. Mary did remarry in July 1565, but life for all of the Marys would probably have been better had she stayed a widow – the marriage to Lord Darnley proved disastrous.