James Melville: Life Story

Chapter 7 : Fencing with Elizabeth I

Elizabeth was as good as her word in regard to Dudley, and Melville and the French Ambassador were invited to stand next to the queen and watch the ceremony in which he was promoted to Earl of Leicester and Baron Denbigh. Melville observed that, wrapping the peer’s robe around him, Elizabeth could not resist tickling Dudley’s neck. Not necessarily the way to promote his suitability as the husband of another woman.

After the ceremony, Elizabeth asked what Melville thought of Dudley, or Leicester, as he now was. Melville answered that the new earl was lucky to have a mistress who appreciated his talents. Elizabeth then went for the jugular.

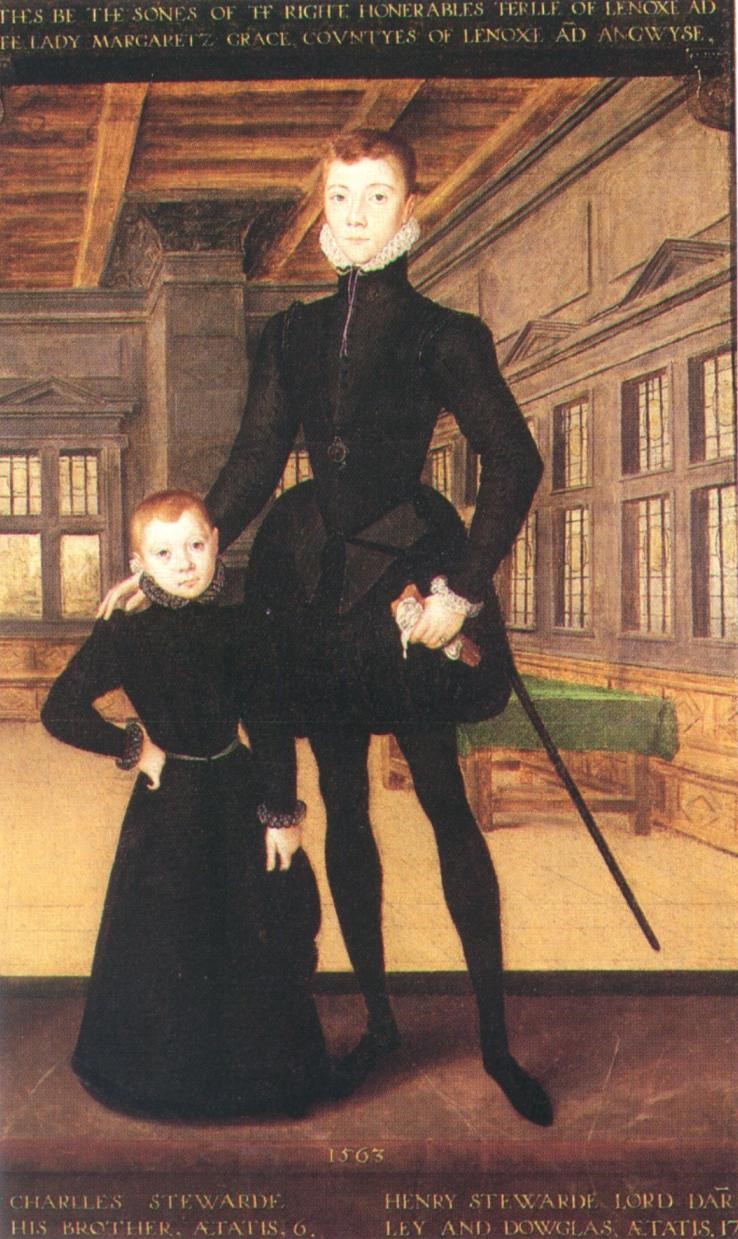

‘Yet,’ she said, ‘you like better of yonder long lad,’ pointing at Henry, Lord Darnley. Darnley was the son of the Earl of Lennox and his countess, Lady Margaret Douglas. Leaving aside Henry VIII’s machinations with the succession in his will, Darnley was Elizabeth’s nearest male heir and second after Queen Mary in a traditional pattern of inheritance.

Melville brushed off the accusation, saying that Darnley was a mere boy, even though he had a commission burning a hole in his pocket to treat with the Countess of Lennox about sending Darnley to Scotland to undertake some legal business with his father – and perhaps for Mary to look him over. The Countess had been intriguing for some time for Mary to marry her son.

Elizabeth was determined to pursue the idea of Mary marrying Leicester, so, as she said she could not talk to Mary directly, she would talk to Melville as familiarly. He remained at Westminster for nine days, and met the Queen at least once, and sometimes as frequently as three times, each day.

The two fenced verbally – Elizabeth pushing Leicester, and Melville indicating that Mary had not even heard the suggestion, and that it might all be discussed as part of a commission, when she had been named as Elizabeth’s heir. Elizabeth countered with the impossibility of naming Mary unless she had shown herself willing to take Elizabeth’s advice. Elizabeth had, however, commissioned lawyers to identify her legal successor – she did hope they would tell her it was Mary!

Melville brandished the fact that before the birth of his younger children, Henry VIII had contemplated leaving his throne to his nephew, James V (Mary’s father) in default of male heirs (actually, Henry had stoutly resisted any such idea).

Elizabeth then told him that, if Mary did not co-operate, she would have to marry and have children herself.Melville, in an astonishing piece of plain speaking to a Queen replied:

‘Madam, you need not tell me that. I know your stately stomach (disposition). You think if you were married, you would be but Queen of England. Now you are King and Queen both. You may not suffer (will not tolerate) a commander.’

Elizabeth then showed Melville her miniature of Queen Mary – ‘accidentally’ letting him see she also had one of Leicester. Melville asked for the latter to show Mary, on the grounds that Elizabeth had the original, but Elizabeth refused. He then asked for a large ruby that Elizabeth had been flaunting, to be sent as a token. The Queen again denied the request but added that one day Mary would have everything, if she followed Elizabeth’s advice. She would, however, send a diamond.

It now being late, Melville was sent away to have his supper with a request to return to the gardens in the morning. At supper, he sat with Lady Stafford, one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, and a close friend, as well as a relative of Elizabeth. Dorothy Stafford, paternal grand-daughter of Edward, Duke of Buckingham and maternal grand-daughter of Margaret Plantagenet, Countess of Salisbury, had married her cousin, Sir William Stafford, the widower of Elizabeth’s aunt, Mary Boleyn, and been exiled in Geneva with other Protestants during Mary’s reign.

Melville had known Lady Stafford and her daughter, Elizabeth, at the court of France, as they passed through en route to Geneva, and had struck up a warm friendship with the daughter.Both ladies were a source of information as to happenings at the English court.

Mary had instructed Melville to entertain Queen Elizabeth, so he told her stories of the countries he had visited, and about the clothes that the women wore – Elizabeth was well aware of the power of clothes to demonstrate power, and political allegiance, and wore clothes in French, Italian and English styles. Melville was asked which he liked best and responded that the Italian style was the most attractive – this was a play on the Queen’s vanity, as Italian ladies showed their hair, and Elizabeth was proud of her curly red-gold locks.

Having begun a quasi-flirtation, Elizabeth then wanted to know who was the prettier, herself or Mary. The silver-tongued Melville replied that the one was the prettiest queen in England, the other, the prettiest queen in Scotland. Elizabeth pursued the matter and he told her she was the fairer-skinned, but Mary was ‘lusome’ (attractive or desirable). He was now backed into a corner with Elizabeth wanting to know who was the taller, what Mary did for exercise, and how well she played the virginals. Mary’s virtuosity, was ‘reasonable, for a Queen,’ he replied.

Later that day, after his audience with the Queen was over, Melville was invited by her cousin, Lord Hunsdon, to take a walk in a gallery, into which the sounds of expertly played virginals were wafting. He drew back a curtain to see the Queen, who, with her back to him, continued playing until she could no longer keep up the pretence of being unaware of his presence. She took her hands from the keys and protested that she never played in front of gentlemen.

He excused his bad manners in intruding on her, and asked for punishment. Elizabeth sat, and placing a cushion for him on the floor, and summoning Lady Stafford as chaperone, proceeded to quiz him on the relative charms of herself and Mary. He had to admit that Elizabeth was the better musician. Elizabeth then showed off her Italian (good, in his opinion) and German (not good.)