James Melville: Life Story

Chapter 3 : Life in France

War was almost continuous between France and the Empire – sometimes in Italy, and sometimes in the area of Franco-Burgundian border. Melville accompanied the army led into Picardy by the Constable in 1553. The results of the various battles were inconclusive, and both armies fell back into winter quarters, with Melville returning to Chantilly with the Constable.

Attempts by Cardinal Reginald Pole (cousin to Mary I of England, soon to be Archbishop of Canterbury) to mediate between France and the Empire were unsuccessful. In 1554 Henri II again advanced, and Melville, although still in the Constable’s retinue, was granted a pension by the King. After a season of war and sieges, both sides claimed victory.

A five year truce was then signed, to facilitate the Emperor Charles’ decision to retire – handing over his Spanish, Burgundian and New World lands to his son, Philip II, and persuading the Imperial Electors to select his brother, Ferdinand, as the new Emperor.

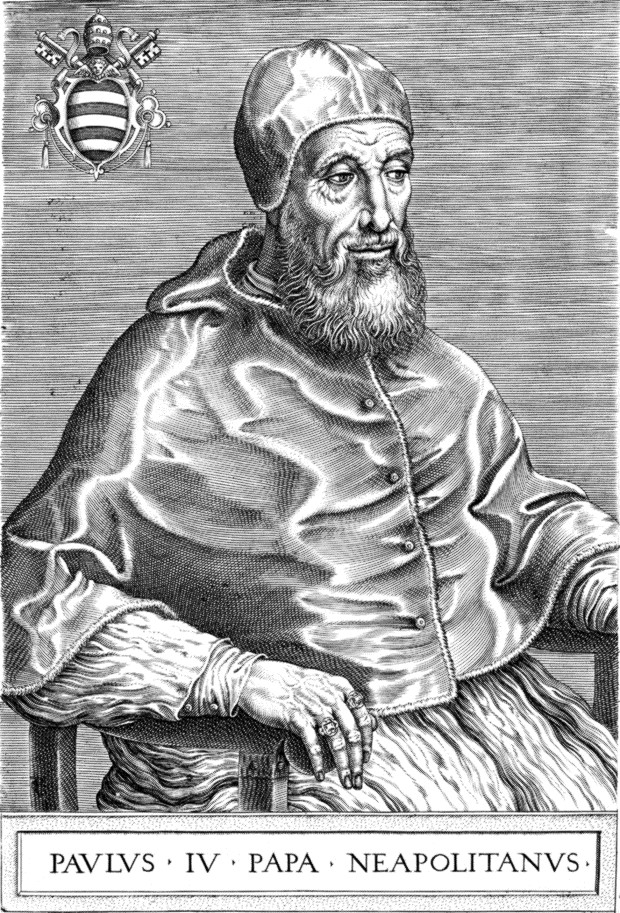

Before the five years of truce were completed, the Pope, Paul IV, tried to persuade Henri II to break it, to support his campaign against Spain in Naples. This idea was taken up by the Guise brothers – François, Duke of Guise and Cardinal Charles of Lorraine, the uncles of the Queen of Scots. The Constable opposed the breaking of the truce but his advice was overridden and France advanced into both Naples and Picardy. The Guise brothers were then horrified to discover that the Pope had made a separate truce.

An angry Philip II prepared for war, persuading his wife, Mary I of England, to support him. The Anglo-Spanish and French armies, the latter including Melville, met at St Quentin where the Anglo-Spanish, under the Duke of Savoy achieved a resounding victory.

Melville was wounded by a severe blow to the head, but managed to escape the field. He mentions being helped by a man he names as Henry Killigrew, describing him as an old friend. Killigrew, a Protestant, had been in exile in France since 1556. It is not clear which side Killigrew was fighting on, but, presumably, the French side.

Failing to follow up their victory, the tables were turned on the Anglo-Spanish when Henri II made a lightening swoop on Calais, capturing the town from the English garrison. Despite this victory, France was at a disadvantage, and was forced to make peace in the treaty of Cateau-Cambresis.

Melville was present at proceedings, still serving the Constable, who had been captured at St Quentin.The French were divided amongst themselves – the Constable in favour of peace, which would release him from bondage, and the Guise party reluctant to have him back at court where they were increasing their influence. On this occasion, the Constable had the upper hand, but, at the urging of the Guise faction, the treaty encompassed oaths for France and Spain to try to restore the Catholic faith in parts of Europe where the Reformation had taken hold.

The English hoped to retain Calais, but, with Queen Mary now dead, Philip had less interest in England, and did not make restoration of the town a condition of peace. England received a sop in that Calais was to be restored after eight years, or a sum of 450,000 crowns paid for, it although it was apparent to all present that this would never happen. Scotland, whose Queen was married to the heir to the French throne, was encompassed in the peace.

With Queen Mary of England dead, there were many who thought that Mary, Queen of Scots was her legal heir, rather than Elizabeth, who had already been proclaimed Queen and crowned. New silverware was ordered for the young Queen of Scots and her husband, the Dauphin, which was engraved with the arms of England. According to Melville, this was the idea of the Queen’s uncle, the Cardinal of Lorraine. It proved to be one of the greatest mistakes the Queen (only sixteen at the time) ever made. The English were angry and protested but were put off with lame excuses.

The Scottish oath to observe the treaty was to be sworn by the Regent, Marie of Guise. Originally, it was planned that Melville should return home to administer the oath, but it was decided to send a more influential figure who could persuade Queen Marie to step up persecution against Protestants – an action she had been unwilling to take. This undermining of Marie’s policy of tolerance in return for support for her rule and for her absent daughter led to dissension, and revolt in Scotland, under the leadership of the Lords of the Congregation. The Lords, led by Mary’s illegitimate half-brother, Lord James Stewart, had converted to Protestantism.

Henri II and the Constable agreed that Melville should return to Scotland to report on affairs. Melville was strictly charged by the Constable to determine whether it would be necessary for Henri II to send troops to support Queen Marie. Melville was to investigate whether the rebellion of the Lords of the Congregation was an attempt to overthrow the Queen and replace her with Lord James Stewart, or to protect the Protestant religion. If the latter, the Constable believed that France should not interfere.

So Melville returned to Scotland, via England. Once in Scotland, Melville hurried to Falkland Palace, to see Queen Marie. He was the introduced by Henry Balnaves (who had had his lands restored in 1556) to Lord James Stewart. The twenty-four year old Melville appears to have struck up a good relationship with Lord James, some four years his senior. Lord James assured Melville that he had no designs on the crown, and would be willing to live abroad to show that he was quite innocent of any improper ambitions. Melville, convinced by his sincerity, set out once again for France.

On his return to France, Melville passed through Newcastle in England, and recounts a strange tale that he picked up there. He met a man who claimed that Henry VIII, on being told that his son would die without children, tried to poison both his daughters, with the effect that, although neither died, they would both be barren. The tale seems quite extraordinary, but Melville appears to have believed it, and interprets other events on the assumption that it was true.