James Melville: Life Story

Chapter 6 : Embassy to England

Melville had intended to return either to the Palatinate or to France, to pursue his career there, as he was unimpressed by the factious state of Scotland. However, he was so charmed by Queen Mary, and so impressed with her ‘princely virtues’ that he felt it his duty to remain in her service, believing her to be ‘more worthy to be served for little profit than any other prince in Europe for great commodity’. He thus accepted her commission, including a pension of 1,000 marks.

In late September of 1564 Mary sent Melville to England to treat with Elizabeth, to send messages to Lady Margaret Douglas (wife of the aforementioned Earl of Lennox) who was her father’s half-sister, and to meet the Spanish Ambassador and Mary’s other supporters.

The main purport of Mary’s letters to Elizabeth was to try to smooth over the dispute that seemed to have arisen between them over the matter of Lennox. Melville was to tell Elizabeth that Mary had been grateful for her advice, and that if she had written anything that could be misinterpreted, he was to assure Elizabeth that only the most positive messages should be taken from Mary’s letters. Mary could not actually remember what she had written – she didn’t think it necessary to copy any ‘familiar letters’ she wrote with her own hand.

The next matter was to agree a meeting between trusted councillors of both queens who would be able to resolve any disputes there might be.

Melville was then to tread carefully, and try to find out what was to be discussed in the forthcoming English Parliament. Mary was aware that Parliament was pressing Elizabeth to name a successor. Elizabeth had refused to do so, but perhaps Parliament would force her hand. In so far as Elizabeth was willing to opine on the succession, she had observed that she knew of no-one with a better right than Mary, but that was not exactly a ringing endorsement. Melville was to hint to Elizabeth that a failure to confirm Mary as her successor might lead people to believe that her protestations of friendship were mere words.

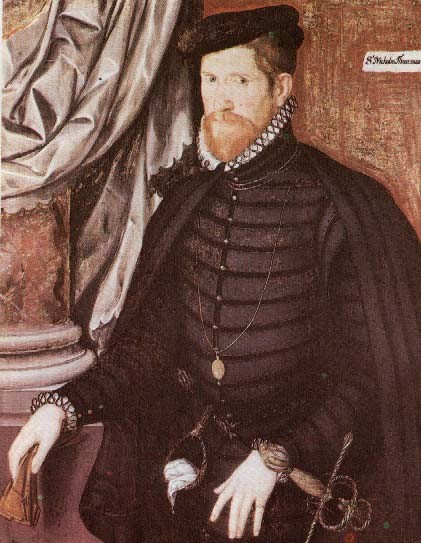

Melville arrived in London and took lodgings at Westminster. As soon as she heard of his arrival Elizabeth sent a message to say she would see him the next morning at 8 o’clock as she was walking in her garden.That evening, Sir Nicholas Throckmorton paid a visit. The Throckmortons were a large clan, based at Coughton Court in Warwickshire, and pretty equally divided between committed Catholics and steadfast Protestants.

Sir Nicholas was in the latter camp. Melville had first become acquainted with him when Throckmorton was Elizabeth’s Ambassador to France during the reigns of Henri II and François II. The two were good friends, and Throckmorton had even chiselled a pension out of the notoriously parsimonious Elizabeth for Melville, during his time in Germany. It may seem quite extraordinary to us that Melville could receive a pension from Elizabeth whilst working for Mary, but no-one thought it at all strange at the time.

Throckmorton, although a Protestant, and highly favoured by Elizabeth, was one of her courtiers who supported Mary as her successor. Throckmorton’s advice was that, should Elizabeth prove recalcitrant in the matter of naming Mary her heir, the sight of Melville cosying up to the Spanish Ambassador would concentrate her mind.

The next morning, Elizabeth sent a servant, a horse harnessed with velvet and two gentlemen, including Sir Thomas Randolph, who had been her Ambassador to Mary the previous year, to fetch Melville from his lodgings.

He met the Queen pacing up and down, as was her custom, in one of the alleys in the Palace gardens. They conversed in French, Melville being more comfortable in that than in his native Scots after so long away, and the Queen, although she might have understood Scots which was similar to English, was fluent in French.The first matter was Queen Mary’s allegedly offensive letter.

Elizabeth brandished a response she had drafted – equally blunt and ‘ despiteful’. Melville, saying that Queen Mary could not remember what she had written, asked to see the original letter. Elizabeth let him read it. It was written in French, and Melville told Elizabeth that, although she spoke beautiful French, she could not be familiar with the everyday French that Mary wrote and spoke, which was rather less flowery between friends (such as he supposed the two queens to be) than Elizabeth might be used to.

Elizabeth allowed herself to be mollified, especially as Mary had made the first move in patching things up by sending Melville. She destroyed her draft letter, and promised to continue in loving friendship with Mary, interpreting anything the latter might do in the best possible light.

Elizabeth then moved on to talk of Mary’s marriage. Had she come to any conclusion following Elizabeth’s suggestion, via Randolph, that she marry an English noble?

Melville answered that Mary had not given the matter any thought – waiting for a conference to be arranged to discuss the matter with all of the other business between the two countries. Mary would send Moray and Lethington, and hoped that Elizabeth would send the Earl of Bedford and Lord Robert Dudley.

Elizabeth pounced on Dudley’s name, saying that Melville obviously held him of small account, as he had mentioned him second – but Elizabeth was going to ennoble him, in front of Melville’s very eyes. Lord Robert, she added, was as dear as a brother and her best friend. She would have married him herself, if she felt inclined to marriage, but as it was, she thought him the best possible husband for Mary. If Mary did marry Dudley, Elizabeth would be very likely to name her as successor as she would then be free of all thought of being hurried to her end.