Thomas Cromwell: Life Story

Chapter 6 : Increasing Influence (1532 - 1534)

Although from January 1532 Cromwell seems to have had the role of managing the King’s business in the Commons, he was still busy with other work, including overseeing building works at the Palace of Westminster and the Tower of London, for both of which he had comprehensive responsibilities in managing construction, and auditing the accounts.

He also acted as Receiver General for what had previously been Cardinal College, Oxford, but was now to be re-founded as King Henry VIII’s College. During this period, Cromwell was closely involved in financial and administrative matters relating to the King’s revenues from vacant bishoprics or other ecclesiastical payments due to the Crown.

It was in April 1532 that Cromwell received his first official position, as Master of the King’s Jewels, and shortly afterwards the low-key, but useful Clerkship of the Hanaper – this brought in a fee every time a patent was sealed. His third office, nowhere near as important as it is today, was as Chancellor of the Exchequer. This trio of offices, although none was particularly significant in itself, gave him a spread of influence across the King’s Household, the legal department of Chancery and the Exchequer. One of his early tasks as Master of the King’s Jewels was to call in the plate that had Katharine of Aragon’s arms as Queen on it, for melting down.

Cromwell’s next three appointments, as Principal Secretary in 1534, Master of the Rolls in 1534 and Lord Privy Seal in 1536, gave him oversight of the departments that executed government business. Although the Principal Secretaryship was not officially his until 1534, he began acting in that capacity in 1532, when the Secretary, Gardiner, was abroad on various diplomatic missions. Gardiner and Cromwell, from an early career together in Wolsey’s household were, by now, at daggers drawn. Whether this was personal dislike, resentment by Cromwell at how easily Gardiner had abandoned Wolsey for the King, increasing distance on religious matters or mutual envy of the other’s proximity to the King, can only be guessed at, but their rivalry continued until the downfall of one of them….

Prior to Cromwell’s appointment, the role of Principal Secretary had not been especially important or prestigious – previous great ministers such as Wolsey, or Cardinal Morton in Henry VII’s reign, had based their influence on the Lord Chancellorship, but from Cromwell’s time to the current day, the position of Secretary of State has been one of the great offices in English, then UK government.

It is this period as Secretary that has furnished the enormous mass of correspondence on which much of our knowledge of the 1530s is based – it should, however be noted, as Cromwell’s biographer Everett points out, that this might lead us to exaggerate Cromwell level of influence. If we had records of other members of the court, a different picture might emerge.

This comprehensive management of administration, never concentrated in one man before, is the basis of the interpretation by the great Tudor historian, Geoffrey Elton, of Cromwell as leading a “Revolution in government”. Elton portrays Cromwell as deliberately undertaking the transformation of the rather ramshackle machinery of mediaeval government into a sleek, well-ordered, bureaucracy.

Over the following years, Cromwell remained close to the King at all times. Unlike Wolsey, or his rivals, Norfolk and Gardiner, he seldom left London, other than to travel with the King on his summer progresses. It is apparent that, although he had clerks whom he trusted completely, in particular, his nephew Richard Williams (later called Cromwell) and Ralph Sadler, he was no delegator. His friend in Antwerp, Stephen Vaughan, wrote warning him that constant “travail of common causes” would impair his judgement for greater things, and that “by overmuch paining his body and cumbering his wits” he would sink into an early grave.

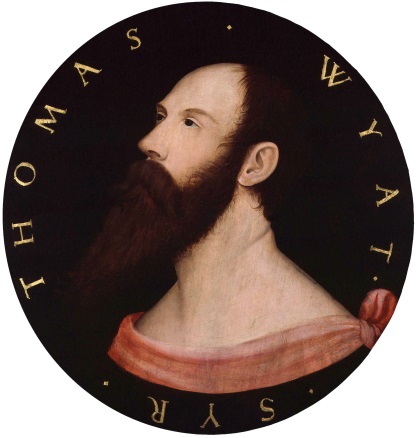

The voluminous documentation that charts Cromwell’s activity is almost entirely business – there is very little to give a picture of Cromwell as a personality – although his friendship for Sir Thomas Wyatt peeps out of a letter. Records also show that he enjoyed hunting and hawking and kept greyhounds. He could draw a fine bow, and played bowls, cards and dice, gambling for high stakes as was common with all Henry’s court. He wined and dined his friends, ordering supplies of wine from Lord Lisle, in Calais, and employed musicians to entertain them.

The breadth of Cromwell’s reading matter is, of course, unknown, but certain works of politics he definitely read, including Aristotle’s “Politics” and Marsiligio of Padua’s “Defensor Pacis”. We can infer, too, that he read Tyndale’s “On the Obedience of a Christian Man” that so beguiled Henry and Anne Boleyn. Many biographers have referred to Cromwell as “Machiavellian”, and claimed that he was a devotee of Machiavelli’s work, and perhaps even knew him in Florence in his time there. Whilst any resident of Florence would have had to go round with his hands over his ears NOT to be aware of Machiavelli in the early 1510s, their different social status would preclude any meeting. There is no certainty that Cromwell read “The Prince” before receiving it as a gift in 1536.

By the end of 1532, the annulment was reaching crisis point. Anne Boleyn had finally surrendered her body to the King, and he was determined to marry her. More’s resignation of the Chancellorship, and the death of Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, in August 1532 finally paved the way out of the impasse. This was to be Cromwell’s moment for obtaining Henry’s heart’s desire through legal means.

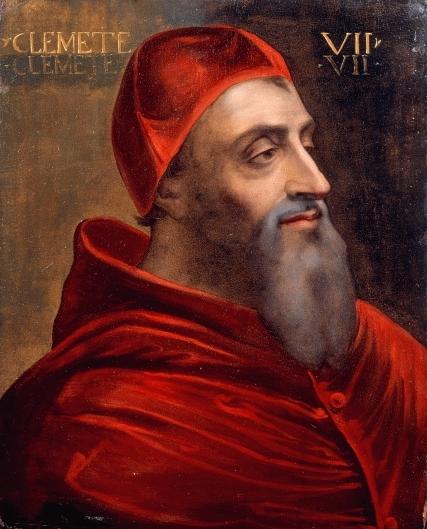

The first step was to obtain Cranmer’s confirmation as Archbishop of Canterbury. Cranmer, an apparently innocuous Fellow of Cambridge, was nominated by Henry in October 1532, and approved by Clement VII in an effort to show Henry that the Papacy was trying to be accommodating. The new Archbishop was consecrated on 30th March 1533. Cromwell had helped to draft a protestation that Cranmer then immediately made, stating that his oath to the Pope could not bind him against God’s Law, or the King’s prerogative.

The second step was to pass the Act in Restraint of Appeals. This Act, again drafted by Cromwell, began with a long and convoluted preamble emphasising that England was an ‘empire’ and thus not subject to any external authority, not even that of the ‘Bishop of Rome’. In consequence, ecclesiastical matters such as matrimony and legitimacy were to be tried and answered within the kingdom, with no appeal. Cromwell, as a master of Parliamentary business, was careful to work with lawyers and clergy through the drafting stage, taking alterations and amendments to give the Act the best possible chance of being passed. In the event, there was very little opposition, although Archbishop Lee of York, and Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester remained opposed.

As well as preparing the Act carefully, Cromwell managed the by-elections that had occurred since Parliament was summoned in 1529, to return members favourable to the King. He also urged all supporters to attend the vote, and discouraged any suspected of not being one hundred per cent on-side, such as Sir George Throckmorton of Coughton, a stout supporter of Katharine of Aragon, from coming to Parliament on the day of the vote. There was some debate in the Commons – merchants feared that the rest of Christendom might not wish to trade with a country that had left the umbrella of Papal Supremacy. Nevertheless, the Act was carried with a majority.

Convocation, headed by Cranmer, and now the supreme ecclesiastical body in England, declared Henry and Katharine’s marriage to have been void ab initio, and his marriage to Anne legal. Cromwell had succeeded where Wolsey had failed.