Thomas Cromwell: Life Story

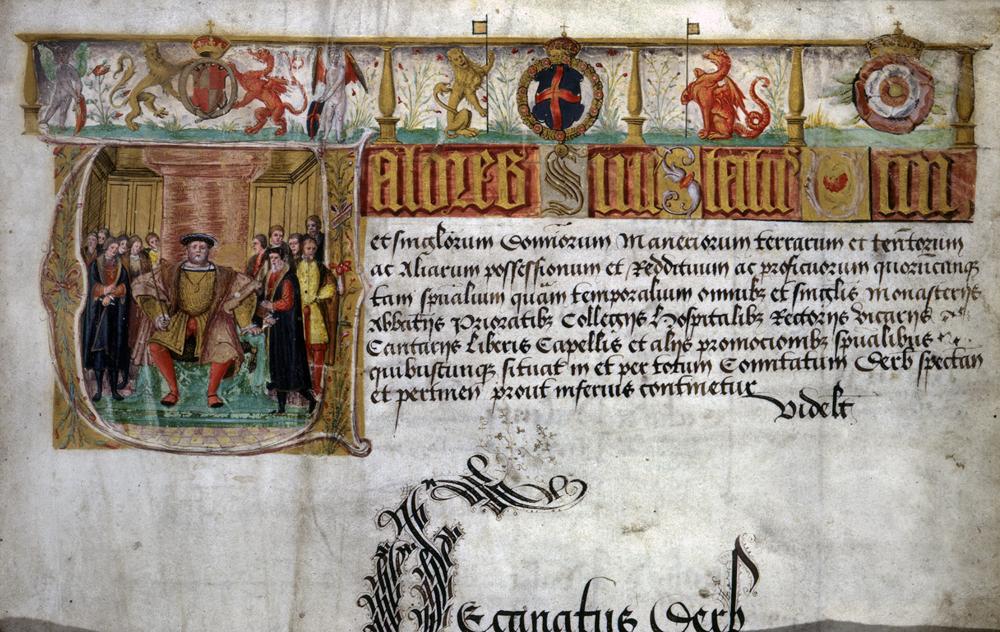

Chapter 10 : Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536 - 1539)

In 1534, Chapuys had noted that the King ‘is very covetous of the goods of the Church, which he already considers his patrimony’ and, as was noted above, legislation in 1534 had implemented a valuation of all monastery lands. By October of that year, Cromwell was drafting a plan for how the wealth of the church could be better disposed of, including the suppression of monastic houses with fewer than ten inmates, and diversion of the revenues to the Crown. The valuation survey was completed and compiled as Valor Ecclesiasticus, the most wide-ranging survey of land since the Domesday Book. Valor Ecclesiasticus determined that the Church was worth some £800,000 per annum. As well as the valuations, the commissions to the surveyors had required them to report on the conduct of the monastic establishments.

Debate has continued for nearly five hundred years as to whether the monasteries were full of corruption, licentiousness and poverty of true religious life, or whether the odd bad example (inevitable in any organisation) was blown out of all proportion to condemn the monasteries, root and branch. Cromwell, personally, seems to have been antithetical to the concept of religious life and was thus mentally prepared to believe everything that confirmed his idea that the monasteries were anachronistic, decadent and potentially harbouring enemies of the King’s supremacy…as well of course, as being awash with cash.

On 21 January 1535, the King gave Cromwell the office of Vicar-General, granting him the power to undertaken visitations (as inspections by ecclesiastical superiors were known) of all monasteries and colleges of priests. Cromwell appointed four men to carry out the tasks on his behalf. All of these men had worked with him previously and none of whom were known for their scruples. A list of seventy-four questions was drawn up, to probe the innermost details of monastic life.

The initial plan was merely to close the smaller monasteries, and send those inmates who wished to continue in the religious life, to larger houses. It just so happened that plenty of evidence was found of corruption and bad practice in smaller houses, and when the bill to suppress them was introduced to Parliament, the Commons were so shocked, that cries of ‘down with them’ were heard. Of the 300 or so monasteries below the threshold of £200 that had been set, 244 were dissolved, and 47 granted licences by the King to remain open. Crown revenues were handsomely increased.

With a huge bounty of land now free for redistribution, Cromwell was inundated with requests to persuade the King to grant some humble petition. The Court of Augmentations was instituted, which Richard Rich, Solicitor General, and Thomas Pope presided over as Chancellor and Treasurer. Cromwell and his men profited handsomely, but it is fair to say that many others of Henry’s courtiers did too, and often those opposed in principle to the Royal Supremacy.

In 1536, Convocation, presided over by Cromwell as the King’s Vicegerent in Spirituals, promulgated the Act of Ten Articles, a declaration of faith that challenged traditional Catholic teachings and began to give an opening to reformist, even Lutheran views. Cromwell then, on his own account, without consulting Convocation, gave orders for parish priests to preach on the Royal Supremacy, and to teach children the Creed and Paternoster in English as well as laying down rules for clerical behaviour, and stipulating how much priests should give in alms. An English Bible, too, was to be in every church from 1st August 1536.

Whatever the views of the Cromwell, the King and his immediate circle on the legislative and religious developments of the period 1529-1536, many outside the south-east of England were very much less content. Rebellion broke out, first in Lincolnshire, and then, more seriously in Yorkshire. The Pilgrimage of Grace, as the latter movement came to be called is covered in detail here. Suffice to say that, after a near-brush with civil war, during which Cromwell was repeatedly cast as the villain by the commons who complained, in time-honoured way, about the King’s ‘evil counsellors’ to avoid seeming to criticise the King, the rebels were overcome. The opinion, not just of the rebels but of many of Henry’s people was encapsulated in the words of Lord Darcy, before his execution.

‘Cromwell, it is thou that art the very original and chief causer of all this rebellion and mischief and art likewise caser of the apprehension of us that be noble men and dost daily earnestly travail to bring us to one end and to strike of our heads and I trust that, or (before) thou die, though thou wouldst procure all the noblemen’s heads within the realm to be striken off, that still there one head remain that shall strike of thy head.’

Nevertheless, Cromwell was riding high. The disturbances of the Pilgrimage of Grace meant that coerced dissolutions of the larger monasteries was politically impossible, but enough pressure was brought to bear for them to surrender voluntarily. Cromwell also continued to act as the King’s right hand man, particularly in the passage of the Act of Proclamations which, despite opposition from the Lords, who feared its use might be arbitrary, confirmed that the King’s Proclamations, in relation to statutes passed by Parliament, had the same force as the statutes.

In 1539, too, many of Cromwell’s enemies were disposed of in connection with the Exeter Conspiracy. It seemed that the Lord Privy Seal could not fail.

The tide, however, was about to turn.