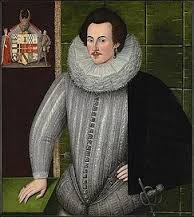

Penelope Devereux: Life Story

Chapter 3 : War and Intrigue (1585 - 1595)

The young Earl of Essex was growing in favour with the Queen, promoted by his step-father, Leicester. In 1585, Elizabeth, after years of importuning by the Puritan party at court, finally agreed to aid the Protestant Netherlands against the Catholic Philip of Spain, who was the hereditary ruler. Leicester led an army onto Flanders, and Essex and Philip Sidney accompanied him. Initially, Leicester had asked for Penelope’s husband, Lord Rich, to take part, ‘though he be no man of war’ but in the event, Leicester changed his plans and Rich remained at home.

Sidney died at Zutphen, and became the stuff of legend. Essex, to whom he bequeathed his sword, married his widow, and attempted to emulate Sidney’s glory. We cannot know whether Penelope felt anything stronger on the death of Sidney than the general outpouring of grief that accompanied his passing. The tale that, on his death bed, he confessed to adultery with her, has been shown to have no contemporary basis.

Following his return from the Netherlands, Essex rose rapidly in Elizabeth’s favour, taking on Leicester’s role as Master of the Horse, and spending long hours with the Queen, gambling, playing cards, dancing, and, ominously, quarrelling vociferously with her.

The war in the Netherlands rumbled on, and Spain sought revenge for Elizabeth’s interference. Rumours grew of a huge armada to be sent against England. Lord Rich was responsible for the militia in Essex, whilst Leicester and Essex were with the Queen at Tilbury. Penelope was probably either at Leez or with her mother at the Leicesters’ home at Wanstead.

The strain of the Armada campaign was too much for Leicester, and to the great grief of his wife, and Penelope, as well as the Queen, he died shortly after. Lord Rich attended the funeral, as did Sir Christopher Blount who had been Master of the Horse to Leicester, and within the year was to comfort the grieving widow. He and Lettice were married in early 1589, giving Penelope a second step-father, who was also a close friend of her brother.

In October 1589, Penelope, Lord Rich and Essex entered into a correspondence that was at best foolish, and at worst, treason. They wrote to King James VI of Scotland, pledging their support for his succession to the English crown, which, they hinted, could not be long in coming. Penelope, who had the code name ‘Rialta’ even sent him a miniature of herself. King James seems to have been rather circumspect in his responses. He knew he was Elizabeth’s preferred successor, and was too wily a hand to risk annoying her (and losing the pension she paid him) by trying to step into her shoes before time.

Penelope’s reasons for embroiling herself in such a risky undertaking can only be guessed at. Her biographer, Sally Varlow, suggests her actions were justified, as Elizabeth’s failure to promote Essex to a prime place in government, together with Elizabeth’s continued harshness towards Lettice, were symptoms of a corrupt government that did not deserve their long-term loyalty. A less-partisan view might be that Penelope and Essex, for all their intellectual brilliance were politically naïve, and demonstrating the factionalism that was to dog the last decade and a half of Elizabeth’s reign.

At some time during the early 1590s Penelope began an affair with Sir Charles Blount, a friend of Essex. Blount was a military man who had seen action in the Netherlands and in the Armada engagement. In the early days, they kept the affair quiet, but she bore him at least three children, possibly five, all of whom were accepted by Lord Rich as his own, although he cannot have been in much doubt about their paternity. Penelope even named her son “Mountjoy”, the title Blount inherited in 1594. Given that Rich was protecting her from public shame by accepting her children, this seems a rather tasteless choice.

Lady Penelope Devereux

Family Tree