Penelope Devereux: Poetry & Patronage

Elizabeth I’s court was the centre of a great flowering of literature, music and drama with the Queen herself being an accomplished musician and a fair hand at writing verse. The courtiers with whom she surrounded herself were expected to be able to provide intellectual amusement and stimulation, not just administrative or military prowess. This emphasis on culture led to the patronage by leading courtiers of painters, poets, playwrights and actors.

This patronage was similar to that already extended by higher members of society to their lower-ranking “clients” and might take the form of money, advancement to posts in the patron’s gift, help in legal matters, or support for advantageous marriages. In return, the artist (usually, but not always, men) would dedicate his work to the patron. The higher ranking your patron was, the better chance you had of selling your work and being recognised, so artists were always seeking recognition from the elite.

When Penelope Devereux came to court in the 1580s, other courtiers who were at the centre of the cultural life of the court included Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, and her brother, Sir Philip Sidney, whom Penelope’s father, the Earl of Essex had wished her to marry. Essex described Sidney as

‘so wise, so virtuous, so goodly; and if he go on in the course that he hath begun, he will be as famous and worthy a gentleman as ever England bred’

and expressed the hope that

‘if God do move both their hearts ... he might match with my daughter [Penelope].’

The Sidney siblings (who were also niece and nephew to Penelope’s step-father, the Earl of Leicester) were two of the most talented members of the court. The Countess gave patronage to the poets Michael Drayton, Ben Jonson, Edmund Spenser and many others, as well as writing and translating herself, and completing works unfinished at Philip’s death.

Both Philip Sidney and the Countess were dedicatees of literary works, he receiving some forty dedications, and she a few less. In fact, the Countess of Pembroke received the second highest number of dedications to a non-royal woman of the whole Elizabethan and Stuart era, preceded only by Lucy, Countess of Bedford.

By 1581 when Penelope appeared at court, Philip, then aged 27, had already produced ‘The Lady of May’ dedicated to the Queen and the first version of Arcadia – a 180,000 word romance he referred to as a ‘trifle’ – and he was now about to embark on a sonnet cycle which took Penelope Devereux as its heroine.

Whether he was actually in love with her, or whether she seemed a suitable subject – she was fair-haired, dark eyed, and beautiful – is unsure. It seems unlikely that he would compose sonnets featuring someone to whom he was completely indifferent, but, of course, admiring a court beauty who was married to another man is not the same as being in love.

The cycle of sonnets, 108 in number, was entitled ‘Astrophil and Stella’. The poet tells of his attraction to the lady, who is, of course, unattainable, and his struggles to overcome it, before dedicating himself to public service. The work was not initially printed, but circulated in manuscript form until published in 1591, after Sidney’s death.

Penelope has been recognised as the heroine from the frequent use of the word “rich”, her married name, and juxtapositions of the word implying her husband, Lord Rich (who was, as it happened, extremely wealthy) does not deserve her:

But that rich fool who by blind Fortune’s lot

The richest gem of love and life enjoys,

And can with foul abuse such beauties blot;

Let him, depriv’d of sweet but unfelt joys,

(Exil’d for aye from those high treasures, which

He knows not) grow in only folly rich.

From Sonnet 24 – Astrophil and Stella – Sir Philip Sidney

There is no record of Penelope’s reaction to the sonnets – but it is hard to imagine that any woman of nineteen would be less than charmed and flattered by being the focus of a man who was much admired at court. Her feelings for Sidney are unknown – the convention of the sonnet cycle is that she should disdain his love. There is certainly no evidence that she had any illicit relationship with him.

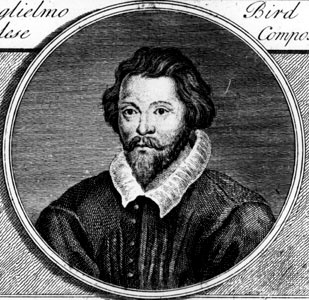

As well as being Sidney’s muse, Penelope inspired or was the dedicatee of other works. It is argued in Sir Philip Sidney and the Circulation of Manuscripts, 1558-1640 by H R Woudhysen that she was the inspiration for several of the secular songs written by the famous Elizabethan composer, William Byrd. More certainly, Edward Paston dedicated his translation of Diana by the Spanish writer, Montemayor, to her and the lutenist Charles Tessier set several of the Astrophil sonnets to music.

Penelope’s interest and involvement in culture continued, and she was closely associated with the extravagant patronage extended by Queen Anne of Denmark in the early 1600s.

This article is part of a Profile on Lady Penelope Devereux available for Kindle, for purchase from Amazon.

Lady Penelope Devereux

Family Tree