Lady Penelope Devereux

Youth and Marriage

Penelope Devereux was probably born in early 1563 to Walter, Viscount Hereford, and his wife, Lettice Knollys. Both her parents were favoured by Queen Elizabeth I at the time of her birth – Hereford because he was then, and after, a loyal and effective servant of the Crown, and Lettice, because she was the daughter of Elizabeth’s cousin and friend, Katherine Carey, Lady Knollys. Penelope had one sister, and three brothers, one of whom, Francis, died young.

Lady Penelope Devereux

Family Tree

Throughout Penelope’s early childhood, which was lived at the family home of Chartley Manor in Staffordshire, her father continued his military service, first in suppressing the Rebellion of the Northern Earls in 1569, and later in Ireland. In 1572 Hereford was raised to the Earldom of Essex, giving Penelope the style of “Lady Penelope.”

In 1575, after a disastrous military campaign in Ireland, Essex died. Penelope’s mother remarried Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, for which she incurred the life-long enmity of Elizabeth, who, although unable to marry Leicester, was very unhappy at him marrying Lettice.

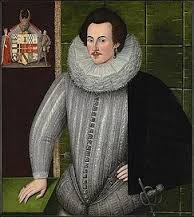

On her father’s death, Penelope became the ward of his cousin, Henry Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon, known as the Puritan Earl. Huntingdon and his wife, who was Leicester’s sister, had charge of Penelope until 1581, when they agreed her marriage with Robert Rich, 3rd Baron Rich. Penelope’s father had expressed a desire for her to marry Philip Sidney (a nephew of the Earl of Leicester) but neither the Huntingdons, nor Sidney’s father, wanted the match.

Before her marriage, Penelope spent some months at Court, where she received royal approval, and attracted the notice of poets, playwrights and gallants. In particular, Philip Sidney, who took her for his muse in his sonnet cycle ‘Astrophil and Stella’ in which her beauty and chastity are praised.

Penelope bore four children who were the offspring of her husband: Robert, Henry, Lettice and Essex. By the early 1590s however, she had embarked on a relationship with Sir Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, and later Earl of Devonshire, that was to last until Blount’s death in 1606.

Penelope and the Earl of Essex

Penelope’s brother, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, was a pivotal figure in the final fifteen years of Elizabeth’s reign. He was a strong supporter of the party that favoured intervention to protect the Protestant Netherlands from their Spanish rulers, and offensive campaigns to prevent the Spanish repeating the Armada of 1588.Penelope was close to her brother, and Mountjoy was one of his closest friends and allies. They supported Essex throughout his turbulent relationship with the Queen, which had lows, such as the disastrous 1591 campaign in the Netherlands, which resulted in the death of Penelope’s other brother, and highs, such as the raid on Cadiz in 1597.

Whilst purporting to be Elizabeth’s loyal supporters, Penelope, Essex, Lord Rich, and later Lord Mountjoy, were in secret correspondence with King James VI of Scotland, promising their support for his accession.

In 1599, Essex, who had been sent to Ireland to deal with the rebellion there, conspicuously failed to obey orders, and, believing that the Queen’s refusal to send all of the money and men he asked for was the doing of his enemies, the Cecils, returned home without leave.

He was tried for dereliction of duty, and put under house arrest. Penelope and their sister, Dorothy, pleaded for him, but to no avail. Penelope grew so intemperate in her correspondence with the Queen that she too ended up in front of the Privy Council for questioning. Essex was eventually released from house arrest, but, financially ruined by the Queen’s refusal to renew his monopoly on sweet wines, led a fatuous and brief insurrection.

Penelope, who was in the rebellion up to her neck, also suffered a brief period of house arrest, but, whilst Essex lost his head on 25th February 1601, she suffered no further punishment than being sent home to her husband. Meanwhile, Mountjoy was pursuing a very successful (from the English point of view) campaign in Ireland.

From Favourite to Outcast

In 1603 the intrigues with King James paid off, as he acceded to the throne of England on Elizabeth’s death. Penelope, who had lost none of her charm and beauty, although now 40 and having borne at least nine children, became a great favourite with the new queen, Anne of Denmark. Penelope was even granted the precedence of the Earldom of Essex, raising her above other barons’ wives.

In 1603, a successful Mountjoy returned from Ireland to be raised to the Earldom of Devonshire and made a Privy Councillor. He and Penelope now lived together openly, and it may have been this that led Lord Rich to seek a divorce. A divorce ‘from bed and board’ was granted to Lord Rich, in November 1605, on the grounds of his wife’s adultery, but, in line with Church of England doctrine, neither party could remarry.

Penelope and Devonshire ignored this ruling, perhaps believing they were so high in the King’s favour that they could afford to flout the law. They were wrong. The King was furious, and banished Penelope from court and refused to accept Devonshire’s pleas that the marriage was valid.

In 1606, Devonshire, although only in his early forties, fell ill and died. He had endeavoured, through the creation of complex trusts, to provide for his children by Penelope, but his Will and settlements were challenged.

Probate was initially granted, then appealed, and finally, Penelope was brought before the Star Chamber on charges of fraud. Accused of being a ‘harlot, adulteress, concubine and whore’ the charges against her were carefully refuted. Before a final settlement was reached, Penelope died.

She was about 44 years old, and, although average life-expectancy was younger in the early seventeenth century than now, it seems a surprising death – she had not succumbed in childbed, the cause of death for many women who died in their childbearing years – and there was no long history of illness.

Her place of death and burial are unknown.