Ladies and gentlewomen who served the queens

Chapter 2 : The Role

So what did all these women do?

In less exalted households, they had very real duties to perform. Whilst no woman who considered herself to be of ‘gentle’ birth would dream of milking a cow, the lady of the manor would certainly superintend her dairy, and there was no shame in being involved in undertaking hands-on tasks in the kitchen, not the day to day preparation of meals, but the more interesting aspects, particularly where ingredients were valuable, such as the making of confectionery or conserves, which required expensive sugar. Lady Lisle made her own quince marmalade, which she sent to Henry VIII, and which he greatly appreciated.

A lady might also brew her own medicines and potions in her still-room. Her women would be expected to learn and to take part. There was also the management of the servants, the supervision of the nursery, the education of the children, the legal and estate business which devolved upon women if their husbands were absent. In managing a household of several dozen people, which the typical knight’s wife might have to do, a second pair of hands would be very welcome.

Higher up the social scale, there was less immediate labour – although Isabella of Castile, whose daughters were the most learned princesses in Europe in their generation, insisted that they know how to manage the traditional housewifely arts.

One of the main tasks of women at all levels of society was needlework. Poor women spun, and richer women sewed, endlessly. It was a woman’s duty to ensure that all her family (a term which included not just, or even, blood relatives, but the people of the household) had sufficient clothes. Only the very richest could afford to employ professionals, and even then the basic garments – shirts and shifts - were made at home. Katharine of Aragon was famous for making Henry VIII’s shirts with her own hands – something he took advantage of well into his courtship of Anne Boleyn, much to that lady’s chagrin.

When they weren’t sewing, they would be making music, dancing, playing chess or reading – usually done out loud. Private reading was very much a development of the late sixteenth century. They would also take part in the vigorous outdoor exercise that was so much a part of the court – hunting and hawking were pastimes for ladies as well as gentlemen. Archery was another sport, and bowls, and marbles were also played. It does not seem that ladies generally played tennis, although Mary, Queen of Scots, and her attendants did.

Gambling was endemic at all levels of society. In the early 1530s, Lady Lisle was worried when her daughter, Anne Basset, who was living in a French household wrote home for money to ‘play’ with. Lady Lisle sent some, but said she ought not to play other than under the supervision of her mistress, and that, in fact, her mother would prefer her to practise her music instead.

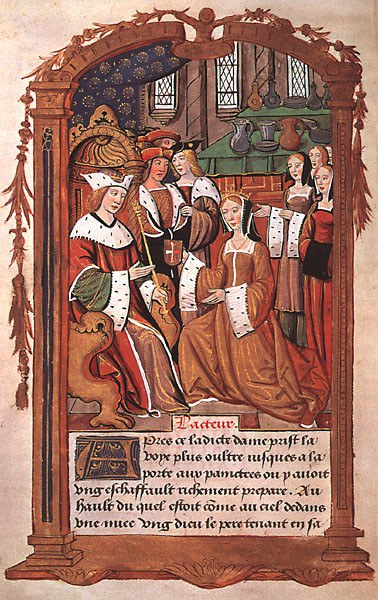

The Queen’s attendants would be involved in court ceremonies – greeting ambassadors, playing in masques, and dancing with foreign kings. Anne Boleyn’s first named appearance was in a masque at York Place, and she danced with François I of France at Calais, whilst her ladies danced with his gentlemen. They also formed an admiring chorus as the king and his knights jousted.

Because the role of the attendants involved the public face of the court, it was sometimes stipulated that they should be good-looking. When Katharine of Aragon was being prepared to come to England, her parents were requested only to send beautiful ladies to wait on her and it appears that ladies performing in masques were selected for their looks, rather than their rank or acting talent.

If a princess married abroad, she would take an entourage of ladies with her, usually including an older woman to give guidance to a girl who might be no more than adolescent. Sometimes these ladies were well-treated, and went on to marry in their new country – two of Katharine of Aragon’s ladies married English noblemen - but sometimes they were very badly treated.

When Henry VIII’s sister, Mary, married Louis XII of France, he insisted on sending all of her ladies home. Mary was distraught, and wrote to Henry:

‘…I am left most alone..for on the morn after my marriage…were discharged and in likewise my mother Guilford with other my women and maidens, except such as never had experience nor knowledge how to advertise (advise) me or give me counsel in any time of need…’

At least Louis arranged for their passage home. Twenty years before, when Juana of Castile married Philip of Burgundy, her husband refused to pay her jointure into her own hands as was customary, so she was unable to pay her household, and he chose not to. The result was that, eventually, Juana’s people left her, and were replaced by Philip’s chosen servants, who were loyal to him, rather than her.