Katherine Willoughby: From Lincolnshire to Lithuania

Katherine’s inheritance was centred on Lincolnshire, and her favourite home was Grimsthorpe Castle. She also had a London house, under the modern-day Barbican. Between 1555 and 1558, she travelled deep into Germany, and then on to Lithuania.

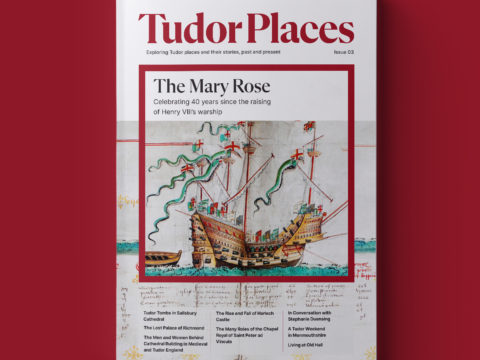

The numbers against the places correspond to those on the map here and at the end of this article.

Katherine was born at Parham Hall (1), one of the properties of the barony of Willoughby de Eresby, inherited from the Willoughby’s ancestors, the Ufford Earls of Suffolk. Parham was one of the properties that was disputed between Katherine and her uncle, Sir Christopher Willoughby, who lived there during the 1520s and 1530s. It is probably to Sir Christopher that the development of the old moated hall into a Tudor mansion is owed. In a final resolution of the family dispute, Parham Hall went to Sir Christopher’s branch of the family, and remained with them until its sale in the 1680s. Today, the property is known as Moat Hall, Parham, and is in private hands.

Although Parham had a parish church, it is probable that Katherine was baptised in the church at Ufford (2), some miles to the south. Patronage of this church was also a perquisite of the Willoughbys. Today, the church, dedicated to St Mary of the Assumption, is famous for its superb fifteenth century font cover and the mediaeval carvings of saints – things that Katherine herself would have disapproved of as inconsistent with the purity of the Reformed faith.

Following the death of her father, Katherine became the ward of Charles, Duke of Suffolk, brother-in-law of Henry VIII. Suffolk and his wife, Mary, known as the French Queen, lived mainly at Westhorpe (3), also in Suffolk. Westhorpe still exists, but it is hidden under a layer of later construction. It is currently in private hands and is run as a care home. The church where Katherine would have worshipped with her guardian and the other members of the Suffolk household still exists.

On the death of Mary, the French Queen, Katherine was swiftly married to her guardian, despite the wide disparity in their ages. During their marriage, they lived in a number of different locations, depending on Suffolk’s military and political duties. One location was Tattershall Castle (4), Lincolnshire, which was granted to Suffolk for his use, following the Pilgrimage of Grace. Henry VIII required Suffolk to live there to maintain order in the county where the rebellion had first begun. Tattershall, now in the care of the National Trust, was originally constructed in the first half of the thirteenth century by Robert de Tattershall. It descended to Ralph, Lord Cromwell, then to his nieces, the elder of whom, Maud, married the 6th Baron Willoughby de Eresby. Tattershall, however, was confiscated by the crown. What remains of the castle is an extraordinarily impressive fifteenth century tower block of expensive red brick. Tattershall passed to the earls of Lincoln and was held by that earl for Parliament during the Civil War.

A second home that Katherine had in Lincolnshire was the Eresby manor (5), near Spilsby. The original manor was built by the de Bec (or Beke) family, and passed on the marriage of Alice de Bec to William Willoughby, father of the first Baron Willoughby de Eresby. The house was extended and altered in the fifteenth century, but this did not satisfy Katherine and her first husband, the Duke of Suffolk, who built a new house, to the south-east of the older hall in the fashionable ‘H’ layout. This house was destroyed by fire in 1769.

Katherine’s most impressive, and presumably favourite property, as it is where she spent much of her time, was Grimsthorpe Castle (6), given to her parents by Henry VIII on their wedding. More on Grimsthorpe here.

Like all members of the nobility, Katherine and Suffolk visited their friends in their country houses away from the court. One of the families she visited, was that of the Earl and Countess of Shrewsbury, at Sheffield Castle in Yorkshire (7). Today, there is nothing visible of the castle, which was originally a Norman edifice, constructed at the confluence of the rivers Don and Sheaf. In the 1270s, the then-owner, Thomas de Furnival, received permission to build a stone castle. De Furnival’s descendant, Joan, Baroness Furnival, married John Talbot – the famous warrior who led Henry V’s campaigns in France and was rewarded with the earldom of Shrewsbury.

The earl of Shrewsbury that Katherine visited was George, the fourth earl, who worked closely with the Duke of Suffolk during the reign of Henry VIII. He died not long after Katherine’s recorded visit, and it was his grandson, George, 6th earl, who, together with his wife, Bess of Hardwick, held Mary, Queen of Scots captive at Sheffield Castle. The castle passed through the 6th earl’s granddaughter, Lady Alathea Talbot, to her grandson, the 6th duke of Norfolk. A royalist stronghold, it was demolished during the Civil War. Recently (summer 2018) a new archaeological dig has been announced, the purpose of which is to clarify the extent of the castle, and the location of the Manor Lodge – a smaller house, used by Bess of Hardwick, in the hunting park.

During her marriage to Suffolk, Katherine was more-or-less obliged to travel where he wished and live in the locations convenient for his service to the king. Following his death, she had more freedom to please herself. When in London, she lodged at another of the Willoughby family properties, a London ‘inn’ (as the houses of the nobility had generally been called), near the gates of the city of London. Today, the site of Willoughby House (11) is commemorated only in its namesake – a 1960s building within the Barbican complex. Out of London, she tended to reside at Grimsthorpe, but in 1551, she rented a house in the village of Kingston, Cambridgeshire (8). This was to facilitate communication with her two sons, Henry, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, and Lord Charles Brandon, who were both students at St John’s College (9).

The village of Kingston is around seven miles west of Cambridge and today is a charming, small settlement, probably not much larger than it was at the time of Katherine’s sojourn. The population of some 200 probably found the appearance of a duchess in their midst a major event – economically, as well as socially. Village life was centred on the Church of All Saints and St Andrew, where Katherine would have worshipped whilst living in the village. She would no doubt have approved the white-washing over of the church’s mediaeval wall paintings following an Order in Council of 1547, promulgated by Katherine’s friend, and fellow reformer, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. These wall paintings have now been revealed, and show a range of decorations, some of which date from as early as the first half of the thirteenth century.

St John’s College, Cambridge, was founded by Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, supported by her chaplain, Bishop Fisher of Rochester. From its earliest days, it had attracted the most progressive students and clerics, and many of its alumni and Fellows became leading figures in the English Reformation, either as educators or politicians, amongst them Roger Ascham, Sir John Cheke, Sir William Cecil and William Grindal. It was perhaps this support of reform that led Katherine to choose St John’s for her sons. But their time there was tragically brief. In the summer of 1551, sweating sickness swept through the university town. The boys came to Katherine’s house at Kingston, but them moved on to the old bishop’s palace at Buckden (10), perhaps to avoid infection, as Katherine herself was ill of some unspecified sickness. She, however, recovered, to hear that her oldest son was mortally sick. She raced to Buckden but too late to see Henry, although she may have been in time to say goodbye to Charles, who died the same day. More about Buckden here.

A couple of years after the deaths of her sons, Katherine remarried. She and her second husband, Richard Bertie, remained strong advocates of Reform – so sincere were they in their beliefs that, with the accession of Mary I to the throne in 1553, they had to make the choice of whether to conform to the restitution of Catholicism (as many of the Reformers did) or go into exile. Katherine and Bertie chose the latter course. Slipping out of Willoughby House (11) under cover of darkness, Katherine made for the rendezvous with her husband in Essex, before they took ship for mainland Europe. Their first point of refuge was at Wesel (12), a bustling city, part of the Hanseatic League, in the duchy of Cleves.

Cleves was part of the Holy Roman Empire, but its duke, Wilhelm the Rich, whose sister Anne Katherine had briefly served during Anne’s period as queen of England, had instituted Lutheranism, as defined by the Confession of Augsburg as the state faith. For Katherine, Lutheranism was not the answer. Her faith had moved beyond that, probably to the position of the First Helvetic Confession of 1536 and the Consensus of Zurich of 1549.

When the city authorities refused to let the burgeoning community of English exiles celebrate the Eucharist as they wished, Katherine and Bertie moved deeper into Germany, into the territory of the Elector Palatine, Otto Heinrich ‘the Magnanimous’. He was certainly magnanimous to the Berties – they were given the castle of Windeck, a fortification built in the 1100s to protect the great abbey at Lorsch, one of the most important early Christian sites in the Frankish empire. Today, the ruins of Windeck are open to the public and are easily accessible from the town.

Whilst Otto Heinrich had been generous in the matter of a home, he was either unable or unwilling to support Katherine and her extended household, which contained a number of English exiles, further. Fortunately, King Sigismund of Poland, and his brother, Nicholas, Count of Vilna, were more able to give financial assistance. Katherine and Bertie made a journey which took them hundreds of miles to the province now called Samogitia in Lithuania.

The early history of Samogitia is obscure – it remained firmly pagan until the early fifteenth century and had autonomy within the grand duchy of Lithuania under its ‘elder’. The elder, during the period that Katherine was there, was Hieronim Chodkiewicz. It may have been the absence of Chodkeiwicz on a diplomatic trip to Rome, on behalf of King Sigismund, that caused Sigismund to give Bertie some role in governing the province – at least according to Foxe. For Katherine, however, nothing could compare with home, and, as soon as she heard that Mary I had died, and been succeeded by Elizabeth I, who was expected to institute a Protestant religious settlement, she and Bertie began the long trek home.

If she had envisaged a life attached to the court, Katherine was to be sadly disappointed. Elizabeth does not appear to have like her and she did not receive invitations to court – nor would Elizabeth permit Bertie to be known as Lord Willoughby de Eresby or called to Parliament in the right of his wife, although that was customary for the husband of a baroness. For the remaining twenty-two years of her life, Katherine spent most of her time at Grimsthorpe, although she did visit friends and family. On her death in 1580, Katherine’s body was taken to St James’ Church, Spilsby (15), close to the old manor of Eresby, and the resting place of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th barons Willoughby. She was joined there two years later by Bertie, and the couple have a splendid tomb. Later, Katherine’s son, Peregrine, 13th baron, and his daughter, another Katherine, were buried there.

The map below shows the location of the places associated with Katherine Willoughby, 12th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby, discussed in this article.

Key

Blue: in current use

Purple: later replacement

Green: ruins

Grey: no trace