John Dudley: Life Story

Chapter 14 : Rebellion

By and large, Warwick and Somerset remained on good terms, although they had a falling out in July 1548 when Somerset refused to remove a Justice of the Peace in favour of a replacement nominated by Warwick – a rejection which infuriated Warwick.

In November 1548, an act was introduced to Parliament that would change England for ever – the Act of Uniformity imposing the use of the Book of Common Prayer. Largely written by Archbishop Cranmer, the Prayer Book was still essentially Catholic in its theology, being in essence a translation of the Latin Mass, yet it was ground-breaking in that it was in English, and undermined, if it did not explicitly deny, the doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the bread and wine actually became the Body and Blood of Christ.)

Henry VIII’s draconian statute against treasons, and the old legislation against heresy had been abolished. Whilst this might have made for a more just society, with the introduction of the Prayer Book, the growing rural poverty, the expense of the war with Scotland and French moves to support their ally, the country was soon in an uproar. Paget warned Somerset that he was handling matters very badly.

Rioting broke out amidst confusion as to the legal status of enclosures. Whilst condemning the practice in new legislation, Somerset had granted pardons to guilty landowners, only to try to control them through proclamations against repeat offenders. Similarly, disaffected countrymen who had uprooted the hedges, were first condemned, then forgiven. Warwick was particularly disgruntled when one of his parks was ploughed up and planted by angry commons.

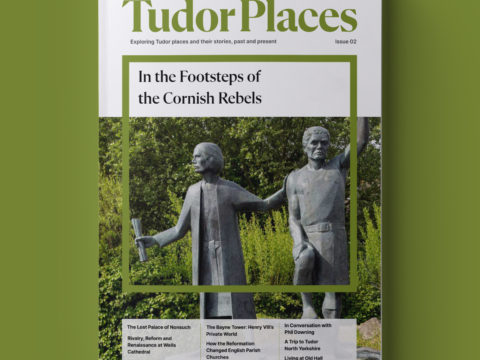

Matters came to a head in two rebellions – at opposite ends of the country and with very different aims. In Cornwall, where many people did not speak English, the imposition of the Book of Common Prayer was deeply resented. The rebels, bearing the old banner that the Pilgrimage of Grace had carried – that of the Five Wounds of Christ, marched on Exeter, determined to protect their faith.

Meanwhile, in East Anglia, another rebellion was springing up, under the leadership of Robert Kett. A was very different from the Prayer Book Rebellion. The East Anglian men had no objections at all to the Prayer Book. Their complaints were economic and they were, initially, at least, far more conciliatory in tone than the Cornish rebels. The Marquis of Northampton was sent to suppress them but Kett had too many men. Northampton retired in ignominious defeat.

Warwick did not seem to be taking the rebellions seriously. He was absent from court in July, complaining of illness, and although he sent orders to fortify his various properties, wrote that he would be unable to serve the government.

Shortly after, he seemed to have a change of heart, and, after much discussion in Council, on 7th August, Warwick was appointed as Lieutenant General against Kett and his rebels. To add to the trouble, on 8th August, Henri II proclaimed war and began an assault on Boulogne, an action which Warwick welcomed as better than secret animosity.

Warwick had charge of some 5,000 men. They arrived in Cambridge, where the rebels had taken over parts of the city. Pardons were offered to all except Kett but before negotiations could be completed, one of the rebels, described as a ‘boy’ pulled down his breeches and insulted the King’s Herald. Warwick’s men responded by shooting him.

Kett offered to meet Warwick, but was prevented from doing so by his men. Warwick immediately attacked the city and captured it, hanging 49 of the rebels out-of-hand. The rebels withdrew from Mousehold Heath to Dussindale, where they were attacked by Warwick’s army. Kett and the other leaders deserted, but the men resisted so bravely that, impressed, Warwick offered a final pardon.

Somewhere between 2,000 and 3,500 rebels were killed, with a loss of around forty of the royal troops. Warwick was modest in his reprisals, to the delight of the townsfolk, who displayed his badge of the bear and ragged staff liberally.

Kett was captured and brought to London where he was condemned, before being returned to Norfolk to be hanged from the walls of Norwich Castle. Curiously, it appears that Kett was a tenant of Warwick’s and there has been speculation that Warwick may have had more involvement with the rebellion than meets the eye. Certainly one of his associates, Sir Robert Southwell, who was in charge of the finances for Warwick’s army was involved – secretly sending funds to the rebels.

Southwell was also a servant of the Lady Mary, being keeper of her park at Kenninghall. Lady Mary was sent letters by the Council, suggesting she had been in some way involved in the Prayer Book rebellion – a charge she firmly denied.

Sir John Dudley

Family Tree