Tender Branches Cut

by Tim Clark

Robert Dudley, Lord Denbigh, and his Tomb at St. Mary's, Warwick

The Beauchamp Chapel in St. Mary's, Warwick, can claim to be the finest late-medieval funerary chapel in England, and, arguably, Europe.[1] It is dominated by the magnificent and status-laden tomb of Richard Beauchamp, fifteenth earl of Warwick, with its rare latten effigy and unique hearse. Its stunning glass boasts the most extensive use of jewelling in England, the only survivor of it from before the Reformation. The statuary, spared from puritan desecration and little restored, is unparalleled. And the chapel is notable for being conceived holistically, with the tomb, glass, and statues all contributing to the story of Earl Richard’s entry into heaven.

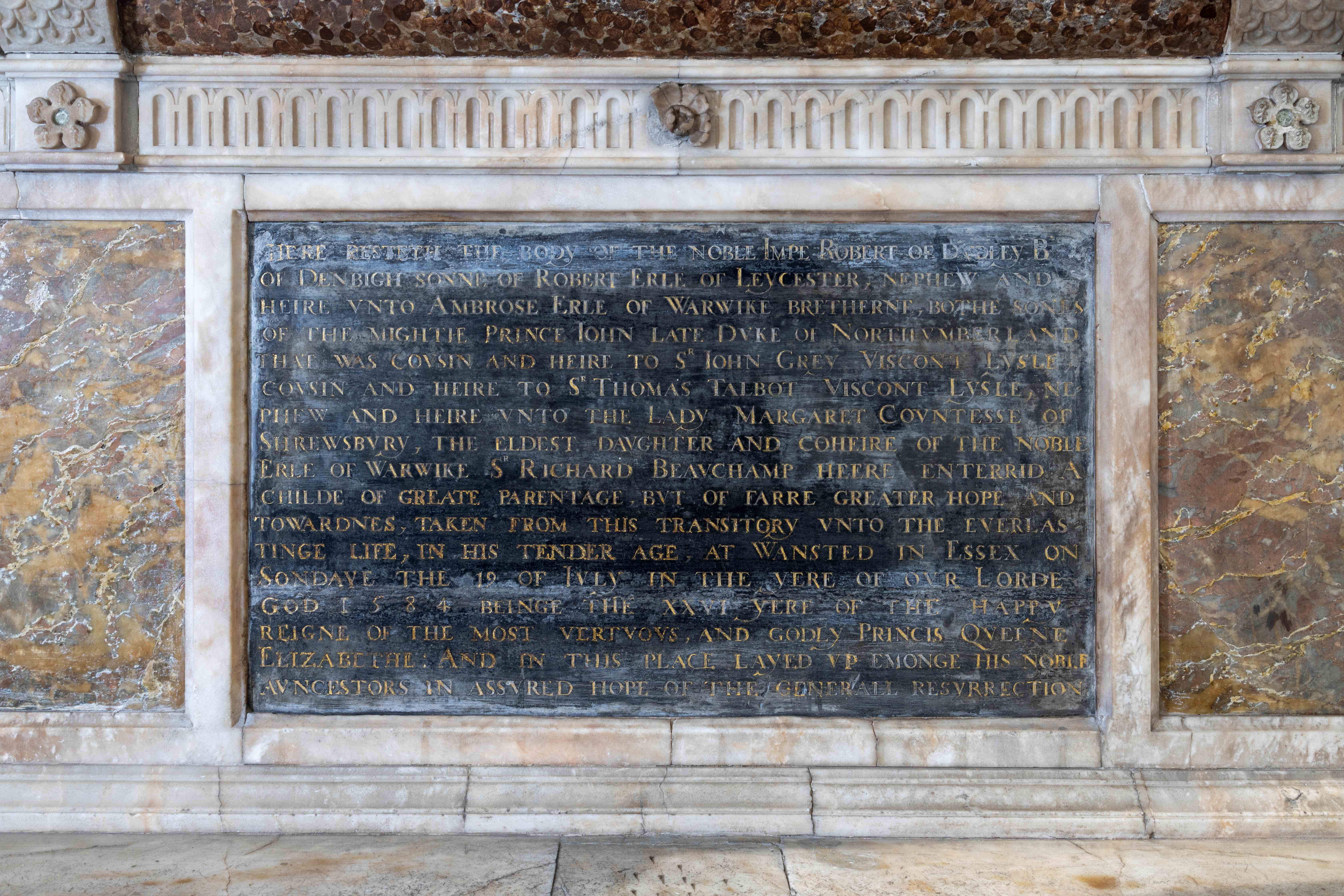

Amid all this splendour it is easy to overlook a small monument, almost hidden from the chapel entrance by the Beauchamp tomb. To the right of the sanctuary is the memorial to the infant Robert Dudley, Lord Denbigh, affectionately known to his parents as the Noble Impe. This article considers why the Impe is buried at Warwick, and what his monument might tell us about his parents’ feelings towards him.

On Sunday 19 July 1584 the Impe’s father, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was at court at Sheen Palace when he received the most grievous news. The Impe had died suddenly at the family home of Wanstead Hall, Essex, just six weeks after his third birthday. The distraught Dudley set out immediately, without obtaining the queen’s permission to leave. His wife, Lettice Knollys, was waiting for him at Wanstead.[2]

It is hard to imagine the pain that Dudley and Lettice felt at the death of their toddler, Dudley’s long-awaited heir, his only legitimate child. Moreover, Lettice was approaching forty-one, so another child was unlikely. But it got much, much worse. The viperous Leicester’s Commonwealth, appearing shortly after the Impe’s death was, according to Francis Walsingham, ‘the most malicious-written thing that was ever penned since the beginning of the world’.[3] It was astonishingly vicious, even by its own base standards.[4] The Impe was, it declared, ‘a son of sin’, and his death ‘as well may be a witness of the parents’ sin and wickedness and of both their wasted natures in iniquity’. This is a (just) three-year-old child it is talking about, and one who had died less than a month before publication. For good measure, a postscriptal text was added in the margin: ‘The children of adulterers shall be consumed, and the seed of a wicked bed shall be rooted out’.[5] Leicester’s Commonwealth accused Dudley of multiple murders and serial adultery, but this must have wounded him the deepest. As we shall see, this compounding of anguish may be reflected in the Impe’s memorial.

The Impe’s funeral was held at Wanstead on 1 August, but his body was taken to Warwick, and entombed in the Beauchamp Chapel on 21 October. To answer why, we must turn to Dudley’s compulsion to validate his dynastic claim.

A useful starting point is Dudley’s will, in which he expressed a desire for a ‘convenient tomb or monument … at Warwick where sundry [of] my ancestors do lie’.[6] He meant the Beauchamps, not his father and grandfather, both beheaded as traitors. Likewise, his older brother Ambrose, Earl of Warwick, wished to be buried at Warwick near his brother and his ‘noble ancestors’.[7]

In short, the Dudleys were by-passing their immediate, disgraced ancestors, and promoting the noble credentials that they could claim courtesy of the Beauchamps, who had been one of the most powerful families of England for some one hundred years from the 1330s. The fact that Richard Beauchamp had died in 1439, and the male line extinguished seven years later, did not diminish the attraction for the Dudleys. John Dudley was indeed Richard’s great-great-great-grandson, and it was no coincidence that he chose the earldom of Warwick on his elevation to the peerage in 1547. When he became Duke of Northumberland, his son John took the Warwick title so as to keep it in the family. The title lapsed on John’s death, and Ambrose lobbied hard for it following the accession of Elizabeth I. His wish was duly granted in 1561.

The most obvious sign of this insistence on their ancestry was the Dudleys’ adoption of the bear and ragged staff as their badge. The bear was the emblem of the Beauchamp family, the ragged staff that of the earldom of Warwick, and they are ubiquitous in the Beauchamp Chapel glass. The Dudleys unashamedly appropriated both badges as their rightful own, often using them together, but also willing to use the ragged staff both in its ‘pure’ form and adapting it as a decorative emblem. It can be seen, for example, in the design of the external timberwork of the stable block at Kenilworth Castle, and it appears stylised as a mouchette on Robert and Lettice’s tomb in the Beauchamp Chapel. Also at Kenilworth, a motif was employed that comprised of the initials RL (Robert Leicester), with the upright stems of the R and the L being ragged staves out of which grew foliage to form the rest of the letters. The symbolism was anything but subtle.

Not surprisingly, bears and ragged staves are prominent on the Impe’s memorial. They are shown, together, on the far left and right above the effigy, both looking towards the viewer. It is as if they are guarding the infant below, warning off an approach. A bear lies at the Impe’s feet, muzzled but wearing a jewelled collar. A frieze of ragged staves, aligned vertically, runs along the edge of the slab on which the effigy lies. To underline the point, there is an explicit statement of the Dudleys’ ancestry engraved on a tablet: a narrative, in English, of the family’s descent from Richard Beauchamp.

The Impe is, therefore, placed firmly in the family lineage, but there are other aspects of his monument that merit consideration. First, Robert and Lettice probably selected the leading workshop of the time for their son’s monument, as it has been attributed to Cornelius Cure, the son a Dutch immigrant who had come to work on Nonsuch Palace for Henry VIII and then settled in Southwark. Cornelius became master mason to both Elizabeth I and James I, and is best known for his memorial to Mary, Queen of Scots in Westminster Abbey (1606), though he died before it was finished, and it was completed by his son. The Cures were also responsible for the tomb of Ambrose Dudley’s widow, Anne Russell, and probably for Ambrose’s himself in the Beauchamp Chapel.[8]

However, more significant for our purposes is the fact that a memorial of this kind was commissioned at all. Depicting an infant in effigy on its own (as opposed to being shown on a parent’s tomb), was most unusual.[9] Indeed, we know of only three earlier English examples: Katherine, daughter of Henry III (died 1257), in Westminster Abbey but now lost; William of Hatfield, son of Edward III (died 1337), in York Minster; and the double tomb of two of his other children, William of Windsor and Blanche of the Tower (died 1348 and 1342 respectively), also at Westminster Abbey. It had, therefore, been over two hundred years since an infant had been granted its own tomb and effigy, and all had been royal children.

At forty-two inches (106 cm), the Impe’s effigy is the height of a five-year old, so his size has been exaggerated to enhance his presence. But, unlike the effigies of Edward III’s children, the Impe is shown as a child. Unbreeched, he wears a heavy, richly woven gown, pleated from the waist, trimmed at the cuff, with pearl or ivory buttons, and leading strings hanging down from the shoulders. There are ragged staves on his coat, prominent on each side of his chest, and forget-me-nots, a reference to the earldom of Leicester, the honour he was expected to inherit. Forget-me-nots also appear on his circlet, interspersed with jewels. One suspects that his dress is fictive, as would the Impe ever had occasion to be presented in such finery?

The Impe’s effigy is an image of what he meant to his parents, of what was lost by his death. Yes, the grandiose display of status is blatant, but he is still a child, dignified and serene, someone to be proud of. It is very different from the few earlier infant monuments, where childhood is negated by the children’s’ depiction as small adults. It takes us into a very personal space, a place of solace, of a life unfulfilled. Perhaps its tranquility and, one might add, defiance, is to some extent a riposte to the vitriol of Leicester’s Commonwealth.

The more sympathetic author of the 1587 edition of Holinshed, chronicling the Impe’s death, wrote of tender branches being cut. This is an allusion to the child’s nickname, for ‘Impe’ meant not only a toddler, but also a sprig or shoot.[10] What he was sprouting from was, of course, the ragged staff, the family tree that had borne his illustrious ancestors the Beauchamps, the legendary Guy of Warwick, conqueror of the Vikings and saviour of the realm, and beyond.[11] This was the Impe’s genealogy, these his role models to whom he would have been a worthy successor. Nobility, thwarted destiny, grief, and disappointment are all brought together in the Impe’s tomb at Warwick.

Footnotes

[1] Richard Marks, ‘Entumbid right princly: the Beauchamp Chapel at Warwick and the politics of interment’, in C. Barron and C. Burgess (eds.), Memory and Commemoration in Medieval England, Harlaxton Medieval Studies 20, (Donington, 2010), pp. 163 – 184, p. 163

[2] Nicola Tallis, Elizabeth’s rival (London, 2017), pp. 207, 208

[3] Quoted by Chris Skidmore, Death and the virgin (London, 2010), at p. 335

[4] A leading contender for its authorship is Sir Charles Arundell, a recusant Catholic: see, e.g., Skidmore (op. cit.), p. 344 ff.

[5] Leicester’s Commonwealth (1641), p. 33. The text is from the apocryphal Wisdom of Solomon, 3:16.

[6] Will of Sir Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, dated 1 August 1587, transcribed copy at the Warwickshire County Record Office, CR1600/LH4

[7] Inscription on his tomb at St. Mary's, Warwick

[8] Adam White, ‘Cure family’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online, 2004)

[9] See, e.g., Sophie Oosterwijk, ‘Deceptive appearances: the presentation of children on medieval tombs’, Ecclesiology Today 43 (2010), pp. 45 - 60

[10] e.g. ‘The first springes or tender impes of the Artechok’ (1578): Oxford English Dictionary (online, 2022)

[11] See, e.g., the depiction of the ragged staff as a family tree in the English sixteenth-century manuscript ‘Descents of the earls of Warwick and Essex’ (Morgan Library, New York)