Meeting of Kings

June 1520

Chapter 2 : Arrangements

Whilst both Francois and Henry took an active interest in the details, organisation was a long-drawn out diplomatic process. In charge of the whole thing was Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester, Lord Chamberlain and a distant cousin of Henry VIII. He had three subordinates, Sir Edward Belknap, Sir William Sandys, Treasurer of Calais, and Sir Nicholas Vaux, Lieutenant of Guisnes and uncle of the young Katherine Parr, one day to be Henry's sixth wife).

Wolsey, who was undoubtedly the instigator and the promoter, was proctor for both Kings and he was supported by the English ambassador in France, Sir Richard Wingfield.

The primary detail to be agreed was the date. Initially, it was set for 1519, but was postponed. Eventually, June 1520 was fixed on after a number of delays that made the French very nervous, as they suspected that England was going to abandon the French alliance in favour of the Empire. They were right to be worried – Emperor Charles was not inclined to see his long-time target, France, in alliance with England, and he tried to spoil arrangements by visiting England just prior to the date on which Henry and Katharine needed to set out.

A request by the English for further postponement to accommodate the Imperial talks was met with a blunt refusal. Nothing later than the beginning of June would suffice. They had the very useful expedient of Queen Claude's health. She was in her eighth month of pregnancy, and would not be able to travel any later. Stymied by chivalry, Henry had to declare that he would not miss the chance of meeting the Queen

" without the which his highness thought there should lack one great part of the perfection of the feast."

Another hitch occurred when rumours were heard in England that the French were equipping a naval fleet, to be sent out as soon as King Henry arrived in Calais. To overcome this, Francois wrote, under his Great Seal, confirming that all Norman and Breton shipping would stay in port for the duration of the meeting.

The next matter to be agreed was the location. Henry was willing to travel to his territory of Calais, but the French Council was insistent that its king should not leave his own lands. In the end, Francois overruled his advisors and agreed to travel into English territory.

Then there was the availability, or rather, lack of, suitable facilities. The English Guisnes Castle, on the edge of the Calais Pale, and the French Ardres Castle nearby, were neither of them sufficiently large for the celebrations planned. It was therefore suggested by Francois, and agreed, that a temporary town would be created.

The location, the Val d'Or, was barren of timber, so all of the materials had to be brought in. For the English side alone, accommodation had to be created for the 3,997 members of the King's suite, and their 2,078 horses, as well as the 1,175 attendants of the Queen and their 778 mounts. No doubt there were similar numbers on the French side. King Henry's guard consisted of 200 halberd bearers and the kitchen staff also numbered around 200. In total, there were some 2,800 tents on the English side.

In addition to the living accommodation, there was the temporary palace, constructed of timber which was joined to Guisnes Castle (where Henry and Katharine actually slept) by a gallery. It consisted of a great hall some 124 ft long by 42 ft wide and 30 ft high (approximately 41m x 14m x 10m) and a huge dining room, bigger than that at Henry's palace of Bridewell - 80ft x 30ft x 27 ft (approximately 26m x 10m x 9m).

There was another chamber almost as large, and a chapel furnished not only with silver, jewels, relics and vestments but with a Dean, ten chaplains and a school of choristers. To make the chapel especially fine, the vestments from Henry VII's chapel at Westminster were brought in for the occasion and real stained-glass windows inserted . The overall effect was spectacular. Apparently the place "l umyned" (illuminated) the eyes of the beholders with its "greate connynge and sumpteuous woorke" as well as the chapel cornice, gilt with "fyne golde". The altar in the Queen's Closet was decorated with "pearles and stones of riches", and, most astonishing of all, twelve gold statutes of the apostles, each as big as a four-year old child, were erected.

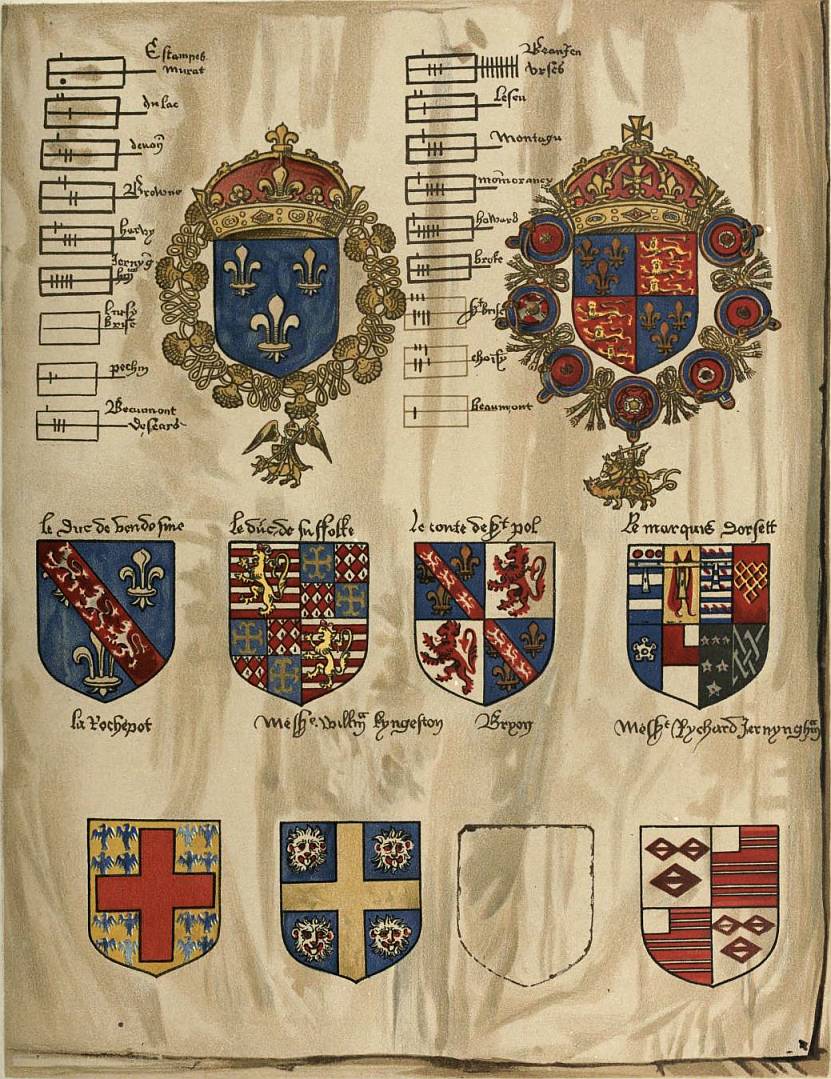

The walls were hung with the King's tapestries, and above was a frieze with figures from Greek and Roman mythology and moulds of the King's arms. In fact, pretty much everything was covered in heraldic symbols.Wriothesley, Garter King-of-Arms, was asked to produce a book to "in picture of all the armes…bestes, fowles, devises, badges and cognisances…[of the] kinges hignes, the quenes grace [and] the French king." These symbols would either be painted, or frequently made of moulds of leather-mache.

The ceilings were studded with Tudor roses, on a gold background. Chairs were smothered with cushions, and cloths of estate, of various shapes and sizes, overlaid with golden tissue and rich embroidery, hung in the state apartments.

Outside, there was also some sort of grand staircase on the exterior and, in the courtyard, the famous fountain that streamed claret, hippocras and water into silver cups.

The thousands of horses required have already been noted – these had all to be brought by ship. The other live animals that accompanied kings – hounds, dogs and hawks – had to be transported as well, together with all of their accoutrements – leads, tack, trappings, collars and so forth.

Then there was the food to be purchased, stored, washed, prepared, served and eaten. Temporary kitchens were set up with the boiling house consisting of a large copper in a tent, a brick bake-house,and a kitchen tent with enormous roasting ranges. The masses of silver plate were arranged on buffets – the favoured method of displaying wealth.

The French accommodation was in some 400 tents. Francois, Queen Claude, and the King's sister, Marguerite, Duchesse d'Alencon, had tents covered in gold. There was a grand French pavilion with images of St Michel, and an interior painted with stars. The French also had a more permanent base in Ardres for entertaining.

The centre of events was the tiltyard. It measured some 900ft by 328ft – nearly as large as the one at Hampton Court and about twice the size of the one at Whitehall.