Thomas Wolsey: Life Story

Chapter 10 : The King’s Secret Matter (1525 – 1529)

By 1525, Wolsey's only friend was the King. The nobles hated and were envious of him; Queen Katharine believed he was favouring the French over her Spanish connection; the Church at home resented his financial exactions, and the Pope was not impressed by his lack of interest in keeping Rome informed of events. Emperor Charles and King Francois had been thoroughly offended by his pride, and the only person to have a good word for him was Charles' aunt, Marguerite, Regent of the Low Countries, whose power was limited.

But these were all known enemies – Wolsey had also crossed someone who would be far more dangerous to him than the rest put together – Anne Boleyn.

Cavendish's " Life of Cardinal Wolsey" is the source for the story that Wolsey had incurred Anne's enmity in the early 1520s by breaking off her romance with Henry Percy, heir to the Earl of Northumberland. According to Cavendish, this had been instigated by the King himself, but Anne vowed revenge on the Cardinal. If she did, he no doubt dismissed it as angry talk by a mere girl. If the Queen could not influence her husband against him, what chance did Anne have?

However, by 1525, Henry VIII had fallen in love with Anne, and, before long, was planning to marry her. It would do a real disservice to Henry to believe that infatuation with Anne was his only reason for seeking an annulment of his marriage. Katharine had not had a pregnancy for seven years, and it seemed her child-bearing days were done. Henry thus had no legitimate male heir, and there were concerns about female succession. In addition, the betrayal of England by Charles and his rejection of Princess Mary meant that the Anglo-Spanish alliance that Katharine represented was now outworn.

Whether Anne was a suitable choice for a second match is a different matter, and, probably at the start of the annulment proceedings, not a definite decision.

Wolsey was blamed then, and subsequently, for Henry's decision to seek an annulment, however, Henry himself stated that Wolsey had, instead, tried to dissuade him. Wolsey was all too aware of the difficulties that would need to be overcome for Henry to gain his freedom. First, the Pope would have to admit that his predecessor had been wrong to grant a dispensation for the marriage, and, second, the Emperor would have to accept the Pope's decision and see his aunt and cousin humiliated.

In May 1527 Henry's campaign opened when Wolsey constituted a secret court, presided over by himself and Archbishop Warham, that cited Henry to appear to answer a charge of living in sin with his brother's widow. Henry therefore was a defendant, and appointed a proxy to act for him, brandishing the dispensation granted by Pope Julius II in 1503.

It was open to Wolsey and Warham to state that the dispensation was insufficient, and perhaps, had they done so, the matter might have passed quickly into the realms of the fait accompli. However, they could not bring themselves to take the hazardous and potentially sinful step of ruling that a Papal dispensation was invalid. They therefore ruled that the matter was open to doubt, and would have to be adjudicated in Rome.

Henry was not, of course, the first King or noble to seek an annulment, and generally, matters proceeded fairly smoothly. Some technical fault was found and the deed was done, with general face-saving all round. In some cases the discarded wives (it was usually, but not always, a wife who was discarded) were persuaded to enter a convent, which allowed the husband to remarry.

In the mid-1520s however, the situation was clouded by two factors – first, the spread of Lutheran ideas challenging the supremacy of the Pope. Clement VII would not be eager to add fuel to these notions by suggesting his predecessor had been wrong to grant the dispensation under which Henry and Katharine were originally married. The second obstacle the sack of Rome by Emperor Charles' forces in May 1527, which resulted in the Pope becoming his prisoner.

Wolsey tried to turn this situation to advantage, by travelling to Avignon, France, in a bid to be recognised as the Pope's regent, able to act for him whilst he was in bondage. However, he was circumvented, both by Katharine smuggling a letter out to Charles V, and by the immediate efforts of his enemies at home to undermine him as soon as he was out of the country. The King was persuaded by Anne's faction, which combined Anne's relatives with Wolsey's enemies (her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, her father, Sir Thomas Boleyn and Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk being the ringleaders) to send messengers directly to Rome.

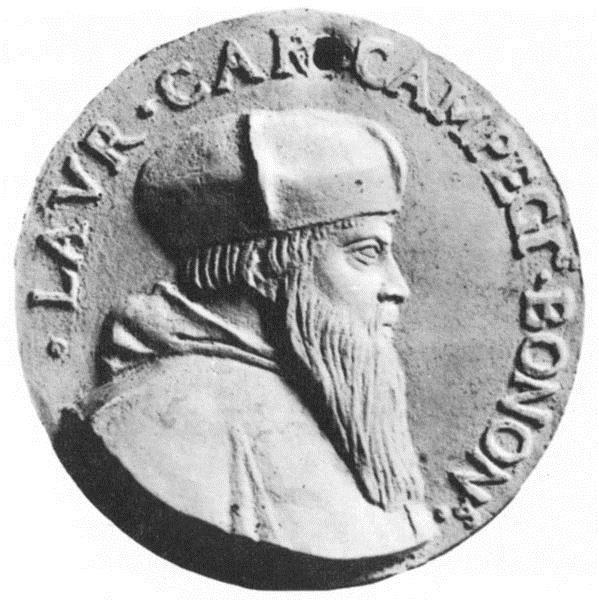

Wolsey failed in his trip to Avignon, the other Cardinals not showing any enthusiasm for Wolsey as the Pope's deputy, and returned to England in September 1527. Henry's messengers had met with no more success than Wolsey's move, so Wolsey was once more expected to come up with a solution. He persuaded Clement to grant a commission to himself, and a fellow Cardinal, Lorenzo Campeggio (who was also Bishop of Salisbury), to hear the case and pronounce on it. Whilst Clement would not openly agree to accept the verdict, he gave a private letter, assuring them he would, whilst, at the same time telling Campeggio the letter was not to be used, and could only be shown to Henry and Wolsey.

In 1529, the famous Legatine Court opened at Blackfriars to try the case of matrimony between Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon. After some opening legal business, Katharine famously appealed to her husband in person, then refused to accept the authority of the Court, appealing directly to Rome. Clement was horrified, but unable to resist the pressure of the Emperor, who now controlled Italy, removed the authority of the Blackfriars Court. On 31 July 1529 Wolsey was obliged to stand up in Court and tell the King that his case was not concluded, but must be heard in Rome. Pandemonium broke out.