Thomas Wolsey: Life Story

Chapter 6 : Archbishop and Cardinal

Late in 1514, Wolsey was promoted to the Archbishopric of York, second only to Canterbury in seniority, although a very distant second in terms of wealth and influence. William Warham, who had succeeded Wolsey's own master, Henry Deane, as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1503, showed no signs of dropping off his perch.

The receipt of the Archbishopric of a York did not come without scandal. The previous incumbent, Cardinal Bainbridge, had spent much of his archiepiscopate as English Ambassador in Rome, and in July 1514 he died there.

It was almost immediately discovered that he had been poisoned and eventually confirmed (by means of torture) that it had been at the hands of a servant of his rival, Silvestri, the Italian Bishop of Worcester, although Silvestri's involvement was never proven.

There were dark rumours that Wolsey had been concerned, although there was never any accusation or evidence brought, and, as Wolsey had stayed well away from the cesspit of politics that was the Roman Curia, it seems unlikely.

Wolsey then received the highest clerical office of all. After much badgering and even more bribing, Pope Leo X appointed him Cardinal on 10 th September 1515. In due course, the red hat that Wolsey coveted so much was dispatched and treated with extraordinary ceremonial "as though it were the greatest prince in Christendom come into the realm." It was conveyed to London and placed on the High Altar at Westminster to be viewed reverently by the great and good of the realm.

A Mass was celebrated by Archbishop Warham, flanked by the Bishops of Armagh and Dublin. The sermon was preached by the Humanist John Colet, who observed, no doubt somewhat to Wolsey's chagrin, that his role, was, like that of his ultimate master, Christ, to minister rather than being ministered to.

Leo refused, however, to give Wolsey the overriding power of Legate a Latere which would have given him overall control of English ecclesiastical matters. These were still in the hands of Warham. This lack of jurisdiction was a disappointment to both Henry and Wolsey, as trouble was brewing between Church and State and, had Wolsey had a free hand, he would have bent the Church to Henry's will.

In 1512 Parliament had passed an Act limiting the right of Clergy to be tried only by Ecclesiastical Courts (the controversy that had raged in Henry II's time, resulting in the death of Thomas Becket.) Not surprisingly, conservative churchmen were against this encroachment on the rights of the church, and a conference was held at Blackfriars where Henry himself listened to arguments on both sides. In the end, he gave judgement, and, prefiguring a later controversy, announced:

"Kings of England in time past have never had any superior but God only…we will maintain the right of our crown and temporal jurisdiction…"

Archbishop Warham requested that the matter be adjudicated by Rome, but Henry did not grant this the dignity of an answer. Wolsey's exact position on the primacy of church versus state cannot be stated with certainty, but it seems likely he agreed with Henry.

The 1510s were a period of increasing anti-clerical feeling, particularly in London, and this was compounded after 1517, by the spread of what the Church considered to be "heresy". In previous ages the Church had responded to heresy by trying to persuade the heretic to "abjure", in which case, he would be given a penance and brought back into the fold of the Church.

As the temperature on religious matters rose, and as more and more people began to espouse the new teachings, the Church took a more hard-line position. It is difficult for us to accept that burning people for their beliefs was considered the right response, but for the people of the time, a heretic was a dangerous criminal who could lead others into sin and imperil their souls. Tough measures were absolutely necessary to protect the innocent. The only variation was on the definition of heretic.

Wolsey, however, seems to have been disinclined to severe punishments for heretics. Whilst he was active in the searching out and burning of heretical works, primarily those coming in from Europe containing Lutheran ideas, he seems to have confined his punishments of heretics to either penance and forgiveness, or a whipping. Wolsey was, of course, for many, the embodiment of clerical sin. He was an absentee priest, he held numerous livings, he lived in a level of unimaginable luxury, and he was not as celibate as he ought to have been. (He had a single, long-term relationship with Joan Larke, by whom he had two children.)

Nevertheless, he seldom exerted himself to punish his severest critics. Even Robert Barnes (burnt in the 1530s for heresy) who had written scathing attacks on the Cardinal was admired for his skill in argument and encouraged to make a general submission in front of Wolsey rather than face the more stringent Episcopal court. Despite being well aware of the need for reform in Church matters and undertaking some mild improvements in his own Archdiocese, it was never a matter of urgency for Wolsey.

It has been claimed that Wolsey was desperate to be elected Pope, and he was put forward on two occasions – 1522 and 1523. Henry VIII pressed his candidacy, and he was promised the support of the Emperor Charles, which extended as far as writing a letter that was deliberately delayed. However it is apparent from Wolsey's correspondence that he did not anticipate any likelihood of victory, and that he had no interest in being Pope. He made no effort to cultivate friends in Rome, never visited, and largely ignored the Roman politics surrounding Papal elections. It may be that in 1528 he regretted his failure to attend to his ecclesiastic career, but it was too late by then.

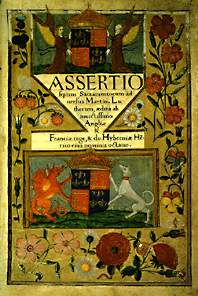

Where he did use his influence at Rome, was to promote Henry VIII's book against Luther, Assertio Septem Sacramentorum. Wolsey wrote a dedication, and also made it very clear to Pope Leo that a suitable honorific would be a welcome gift to the King. Leo took the hint and bestowed the title of Defender of the Faith on Henry, which title has been proudly displayed on English, and British, coins ever since.