Thomas Wolsey: Life Story

Chapter 3 : A New Reign (1509 – 1513)

There is some debate amongst historians as to whether Wolsey was passed over in the first few months of Henry VIII's reign, because of the dislike of that doyenne of the Tudor house, Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, who was nominally regent for the remaining few weeks of Henry VIII's minority (he was not 18 until 28 th June).

It is not clear whether Wolsey was not reappointed as Royal Chaplain, or whether he is just not mentioned in the various household lists. Biographers Williams and Matusiak contend the former, whilst Gwyn believes that latter. His post of Almoner initially went to Dr John Edenham, but Edenham died in September 1509 and Wolsey resumed the post.

Whether or not Wolsey was passed over in the spring and summer of 1509, he was certainly back in favour by the autumn and a string of offices came his way in the next four years: among others, Privy Councillor (by November 1509); Registrar of the Order of the Garter (April 1510); Prebend of St George, Windsor (February 1511) and Dean of York (February 1513).

So why was Wolsey so popular with the new king? There is, on this, as on so many things, several schools of thought. The first is that the young Henry VIII had no interest in conducting government business, and wanted only to enjoy himself and spend his father's money. In this scenario, Henry is presented as easily led and strongly influenced by Wolsey, who was a witty and eloquent man. This idea is borne out by some of the later Ambassadors' reports about Wolsey really wielding the power, and Henry as a figurehead.

If one looks more closely, however, it is apparent from the internal government papers that Henry and Wolsey had a worked out what might nowadays be called a "good cop-bad cop" routine with one feigning anger or disgust at a foreign request whilst the other expressed regret that it couldn't be fulfilled and promised to look into it.

Another school of thought, is that Henry was always a clever man at choosing others to do the grunt work, but that he was always the ultimate arbiter, and that, as soon as Wolsey failed to deliver what the King wanted, he went.

It seems likely that in the early days of his reign, Henry, eighteen, handsome, gifted, athletic and energetic may have found the day-to-day details of administration and left them to his able Councillor, but, to quote Cavendish, he gave power to Wolsey because

"he was most earnest and readiest of all the King's Council to advance the King's only will and pleasure, without respect to the case."

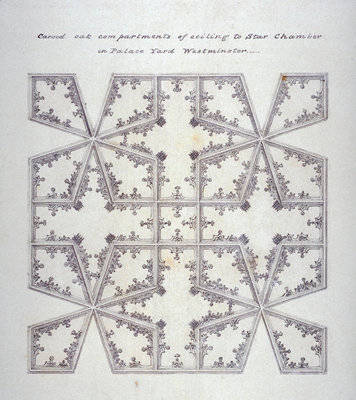

The King's Council, comprising about a dozen men, met regularly in the Star Chamber at Westminster. If Henry were not present, and it seems that during his early reign, he was more frequently out hunting, then he needed a reliable go-between, and this seems to be the role that Wolsey took.

It was not until the other Councillors found that this gave Wolsey a unique position of influence that they realised they had been side-lined.

Henry and Wolsey also got on well personally. Wolsey was described as by the Venetian ambassador as "handsome" and even by his enemy Polydore Vergil (the historian of Henry VII's reign) as a man of distinction. He also had many tastes in common with Henry. He was musical (he played the lute and had a well-trained choir at a later date), interested in building, and a patron of the Humanists.