Thomas More: Life Story

Chapter 8 : The King's Service

More’s solution to the alum confiscation brought him into the spotlight, and shortly afterwards, he was appointed to use his commercial expertise to assist Cuthbert Tunstall on a diplomatic mission to the Low Countries to negotiate about the wool and cloth trade with England.

More’s absence from London lasted about six months. During it, he met up with Erasmus, now in Louvain, and made friends with Pieter Gillis, known to posterity by the Latinised name, Petrus Aegidius. The fertile conversations the three men had were the genus of More’s most famous and enduring work, Utopia, which was a satire in the form of a description of a mythical country – perhaps ideal, perhaps not.

At the end of six months, although the diplomatic mission continued, More asked Wolsey for permission to return home, which was granted. He explained his reasoning in a typically drily humorous letter to Erasmus:

‘A liberal allowance was granted me by the king, for the servants I took with me, but no account was taken of those I was obliged to leave at home. And yet, though you know what a fond husband I am, what an indulgent father, and gentle master, I was unable to prevail on them for my sake to remain fasting even during the short time until my return home.’

In early 1516, More was offered a formal royal appointment. It was probably as a member of the King’s Council, with a salary of around £100. He was torn over whether to accept. He did not want to give up his legal practice and his part in the City’s busy social and commercial life, yet the temptation to be at the heart of affairs was strong. Ammonius (whose letters are always rather sour) wrote to Erasmus that no-one was more assiduous than More in attending on Wolsey. At the same time More’s father, not yet a judge, but moving up the ranks of the legal profession, was appointed as a legal assessor to the King’s Council.

In the spring of 1517 there was serious rioting in London. There was deep resentment of ‘aliens’ as foreigners were called – in a prejudice that has many parallels throughout English history, the foreign merchants were resented for taking trade away from Englishmen, and accused of stealing their work and their wives. More, as one of the representatives of the City authorities, urged the rioters to calm down and return home, but he and his colleagues were ignored as St Martin’s Church was damaged, and a number of foreigners’ homes were broken into. According to a letter he wrote to Erasmus, More was later involved in trying to determine the origins of the riots.

Biographer Richard Marius suggests that the experience of the Evil May Day riots (as they became known) had a profound effect on More’s perception of the value of good order, and that, rather than continuing as the champion of the poor, which is a reasonable interpretation of Utopia, he sided firmly with authority and order.

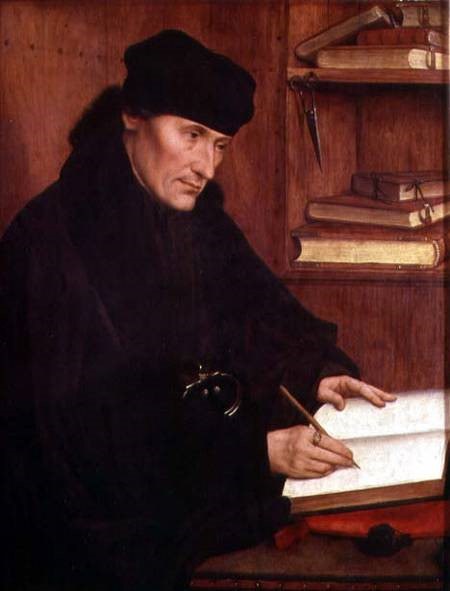

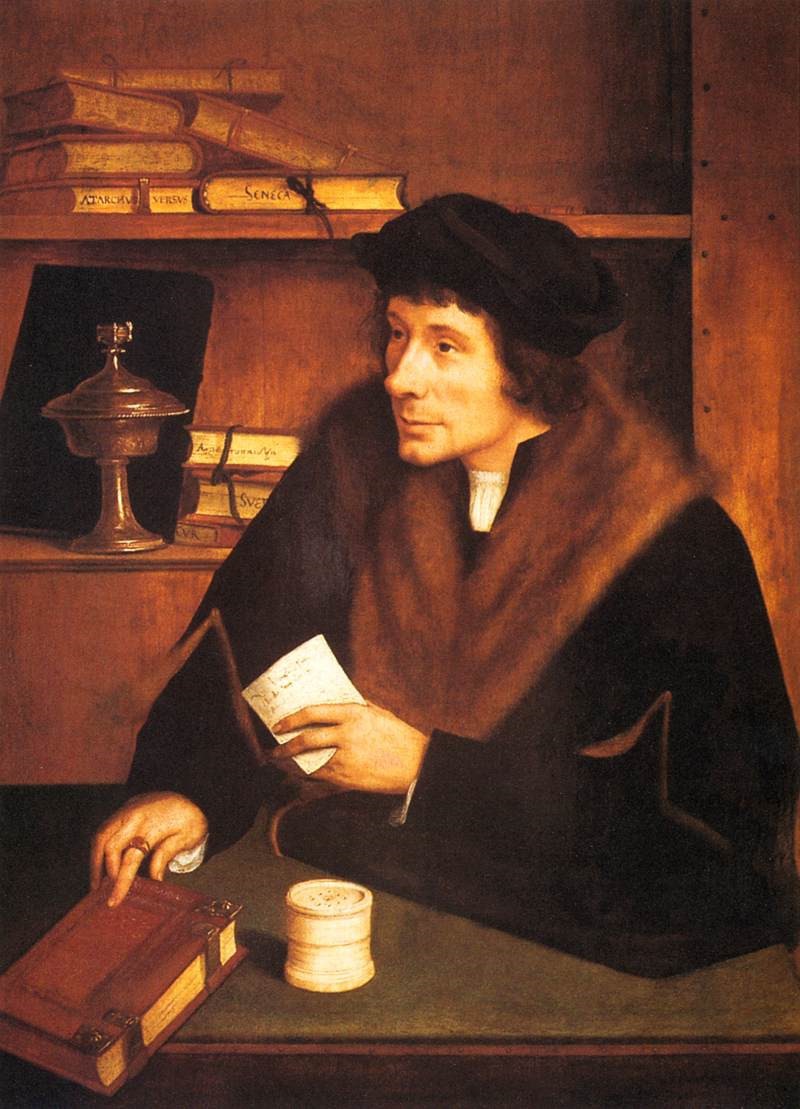

Shortly after Evil May Day, More again undertook a diplomatic visit to Calais. Whilst he was there, he received a joint gift from Erasmus and Aegidius that was to represent their friendship. It consisted of a diptych by the painter, Quentin Matsys, showing Erasmus on the left-hand side of the viewer, wearing a ring given to him by More, with his New Testament in the back-ground and Aegidius on the right, reading a letter from More, and holding a volume of Erasmus’ work.

Wolsey had been appointed as Lord Chancellor at the end of 1514. He had no legal training, but was later to gain a reputation as a friend to justice, with swift decision making and a tendency to favour poorer litigants. This was widely resented by lawyers as amateurism and by the nobles, whom he forced to conform to the law in a way they had previously avoided. Part of his plan was the creation of the Court of Requests, where poor men might plead, and it was to this that More was finally appointed when he decided to take the King’s offer of a formal position in 1518. He was sworn in at Reading Abbey that March. Henry’s admonition to More was to serve God, and then the King.

Despite an age gap of some twelve years, More quickly struck up a warm personal relationship with Henry. The King would walk arm-in-arm with his new Councillor, and would invite More to join him and Queen Katharine after supper to discuss the vast range of topics that particularly interested the King.

Astronomy and theology were two subjects on which they conversed. Henry was writing a book to refute the arguments of Luther, and More was one of the scholars with whom he tossed ideas back and forth. We can also see More’s influence in the extensive humanist education that Princess Mary received. By 1520, he was on such good terms with the King that he was included in the huge retinue of courtiers at the Field of Cloth of Gold, the sumptuous summit meeting between Henry VIII and Francois I. Nevertheless, More never built too much on this relationship, apparently saying that if his head would gain Henry a castle in France, it would surely go.