Anne of Brittany: Life Story

Chapter 2 : Duchess of Brittany

Within weeks of the defeat, Francis was dead, badly injured by a fall from his horse. Anne and her sister, Isabeau, withdrew to Guèrande, near Rennes, and Anne was proclaimed as duchess. Duke Francis had left the guardianship of Anne and his duchy to the Marshal de Rieux, but immediately Charles VIII and Anne of Beaujeu insisted that Charles had the right to act as Anne’s governor.

Anne was only twelve, and it is difficult to know how much of the Breton government’s actions can be directly attributable to her, but she was certainly involved in decision making, and acted publicly as an independent duchess. She confirmed Rieux in his position and the Estates-General were called to acknowledge her and swear allegiance. Cash for paying the soldiers that Anne and her ministers anticipated might be required for defence, was raised by pawning the royal jewels and plate, and new coinage was issued.

Anne need allies abroad and turned to the traditional enemies of France – England, Spain and Burgundy. Henry VII of England owed his safety in exile to Anne’s father. There is no information on whether Henry and Anne had ever met (she was only eight when he left Brittany) but he certainly knew her nobles, and, presumably in a spirit of gratitude, entered a treaty with Maximilian and Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, to support Brittany against the French.

There was no thought of a woman ruling without a husband. All depended on Anne’s choice of suitor. Henry VII was already married to Elizabeth of York, otherwise he might have been a suitable choice. Louis of Orléans was married to Jeanne of France, but was willing to instigate an annulment to marry Anne. There was also Juan, Infante of Spain, and various Breton nobles, including her cousin, Jean de Châlon, Prince of Orange and, once again, the powerful Alain d’Albret, whose suit was strongly favoured by Marshal de Rieux.

Anne’s choice was the widowed Maximilian of Hapsburg, King of the Romans, who would one day succeed as Holy Roman Emperor. At the same time, a match between her sister Isabeau, and Maximilian’s son, Philip, was mooted. Anne wrote to Maximilian personally, and the marriage was agreed. Jean de Châlons agreed to support the match, rather than see Anne married to d’Albret.

The ceremony, by proxy, took place in early 1490 (not December as noted on Wikipedia) in Rennes Cathedral. Maximilian’s proxy was the Count of Nassau, who, after declaring the vows on behalf of his master, lay down on the bed with Anne and touched her with his bare leg, in token of consummation. The marriage treaty was straightforward. Should Maximilian die before Anne, and they had no children, she would remain sovereign duchess, if she died first, with no children, Maximilian would have no rights in her territory. If they had an heir who was a minor on Anne’s death, Maximilian would control the duchy, but would be limited in his actions. Anne was now Queen of the Romans, as well as Duchess of Brittany.

The marriage with Maximilian was in direct contravention of the Treaty of Le Verger, and there was no possibility that the French would not contest it. Alain d’Albret was also infuriated. He wreaked his revenge by surrendering Nantes to the French army – apparently in hopes that Charles VIII would then permit him to marry Anne (until Maximilian and Anne consummated their marriage in person, it could be annulled). The 5,000 crown pension promised him by Charles probably helped him to make the decision to betray Anne.

Anne had few troops, compared with those available to the French – and Maximilian, who should have come to the aid of his wife, was nowhere to be found. Charles besieged the duchess at Rennes, and Anne suffered the misery of seeing her mercenary troops demanding more money than she could pay, whilst there was no sign of help from her husband.

Charles offered terms: if she resigned the title of sovereign duchess, she would be granted a large pension, and a choice of three husbands, from amongst his nobles. Anne rejected his offer. Apart from anything else, she replied, she was already married. If Maximilian never came for her, she would not marry anyone else, and if Maximilian were dead, she would only accept a king or a king’s son as a spouse.

The French king’s next, more successful ploy, was to pay off Anne’s mercenaries, who withdrew. He then offered once again to give her a pension, and send her to Maximilian, leaving him in possession of her duchy. Finally, a third option was proposed: Charles would renounce his betrothal to Marguerite of Austria, Maximilian’s daughter, and marry Anne himself. Charles had already jilted Elizabeth of York in 1482, to marry Marguerite.

Between a rock and a hard place, Anne’s councillors persuaded her to relent. Continued resistance would have led to Charles taking Brittany as a conqueror, and causing widespread devastation. By accepting him as her husband, she would not be shamed, as she would be Queen of France, and also, in name at least, remain as duchess.

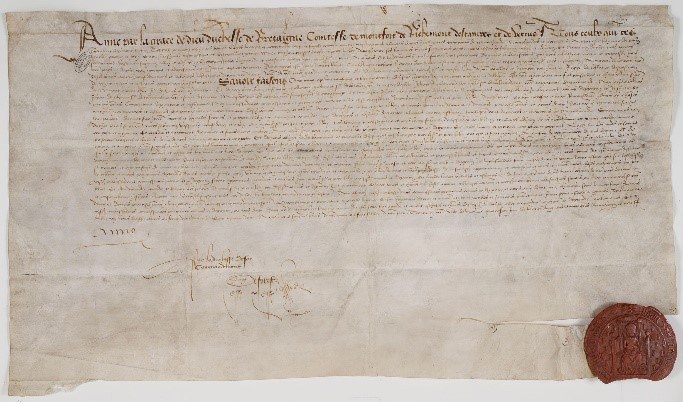

The treaty was signed. Anne would marry Charles, and, if they had no children before his death, she would be free to return to Brittany as duchess, but could only remarry to Charles’ heir (still Louis of Orléans) so that the duchy would remain linked to the French crown.