Dowries & Marriage Settlements

Chapter 2 : Dowry

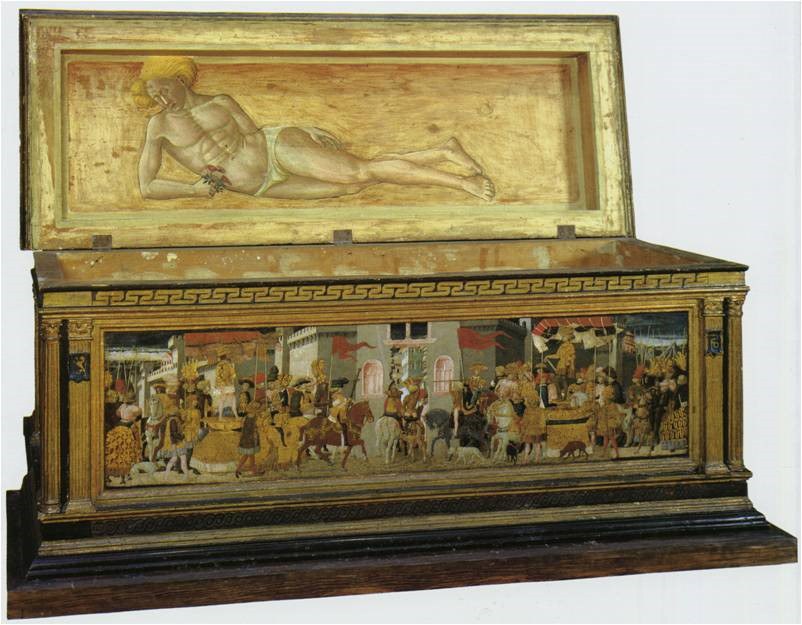

The dowry was the payment that the bride’s family made to the groom’s family. It usually consisted of cash and moveable goods, often including livestock. In Italy, the custom was for the bride’s dowry and goods to be carried to her new home in beautiful painted chests called ‘cassone’.

If a man died before his daughters were married he would usually make provision in his will for dowries for them. This could lead to complications if it was not specified whether each daughter should receive a specific amount, or whether they should share in a single pot of money.

For example, John Hardwick of Hardwick, father of the famous Bess of Hardwick, left a sum of money for dowries for his daughters, mentioning five, who were to have 40 marks apiece. But if his pregnant wife was to bear another daughter, she would also be entitled to 40 marks, and if any of the girls died before marriage, the same sum of money was to be shared amongst the survivors.

Dowries for royal women could be extensive. Mary, daughter of Henry VII, had a dote of 300,000 crowns – around £60,000 – in 1514. Marie of Guise took 100,000 crowns to Scotland in 1536. Katharine of Aragon’s dowry was 200,000 scudos (c. 200,000 crowns). She took part of it in cash, and part in plate and jewels.

Anne of Cleves’ marriage treaty specified a dowry of 100,000 gold florins (£16,500 at the time), of which 40,000 was to be paid down, and the remainder after a year.

The dowry became the property of the groom’s family. For royal marriages, there might be an agreement that if the husband died, and there were no children, the dowry would revert to the bride or her family. This was the basis in the 1530s for negotiations around a possible dowry for the Lady Mary, the daughter of Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon. As her parents’ marriage was held to be invalid, it was argued that she was entitled to her mother’s dowry, which she could take to a potential husband.