Cromwell and the English Bible

Chapter 3 : Cromwell and the Bible

Cromwell is usually described as a radical in religious matters, an early Protestant (although the term was not in common currency until after his death),but there were many shades of evangelicalism between the strict conservatism of men such as Bishop Gardiner,Cromwell’s nemesis,and ‘heretics’ such as Tyndale. Whereas Anne Boleyn and her family, and Archbishop Cranmer are referred to by Eustache Chapuys, that inveterate reporter of gossip, as ‘Lutherans’ he does not use that term of Cranmer.

Cromwell’s Will, made after September 1532, asks for the intercession of the Virgin and the Saints, allocates money for several houses of friars, and for prayers for his soul, a traditional Catholic practice that by 1532 was excoriated by Tyndale and Luther.His stance was certainly anti-clerical - the Chronicler, Edward Hall, himself having reformist tendencies recorded that Cromwell ‘could not abide the snoffyng pride of some prelates’, but whether he supported doctrinal changes in the early 1530s is questionable.

Cromwell moved intellectual circles, and a later correspondent wrote that he treasured the memory of ‘divers dinners’ at Cromwell’s home at Austin Friars where he had heard ‘such communication which were the verye cause of the begynninge of my conversion’ but he also maintained friendships with conservatives such as Edmund Bonner, later Bishop of London under Mary.

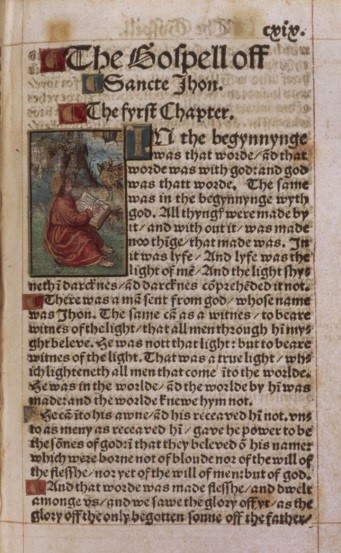

Exactly why and when Cromwell himself first read an English Bible is unknown. According to John Foxe, on one of Cromwell’s trips to Rome in the 1510s he had memorised Erasmus’ New Testament. This would certainly suggest a lively interest in religion, beyond just form, and together with his naturally inquiring mind would probably have led him to read Tyndale’s work. With his contacts in the cloth trade he would have had easy access to a contraband copy, most likely through his friend and associate in Antwerp, Stephen Vaughan, whom Cromwell later warned that he was becoming suspect for Lutheran views.

Whether or not Cromwell entertained Lutheran doctrinal views cannot be proven but what can be, is his commitment to the Bible in English. Foxe, in his ‘Book of Martyrs’ wrote that Cromwell’s

‘whole life was nothing els, but a continuall care and travaile how to advaunce and futher the right knowledge of the Gospell’.

In 1534, the Convocation of Clergy, now the governing body of the English Church, under the King, petitioned the monarch for a full translation of the Bible for the edification of his subjects.It was suggested that Tyndale might be employed to do it, on condition that he ceased to write the offensive polemics against the King’s annulment that had poured from his pen. Henry, although he was prepared to consider an English Bible was apopletic at the thought of encouraging Tyndale whom, according to Cromwell, he considered to be ‘replete with venomous envy, rancour and malice’.

A translator more acceptable to the King would have to be found.