James V: Life Story

Chapter 2 : Factions and Rebels (1515 - 1524)

James was now, at the age of three, effectively an orphan. For the next thirteen years the various factions ranged at the Scottish court attempted to control his person, and the Government. In order to prevent any one group gaining control, it was agreed that various nobles would rotate the guardianship of the King, who was housed in the main defensible castles in Scotland’s central belt – usually Edinburgh or Stirling.

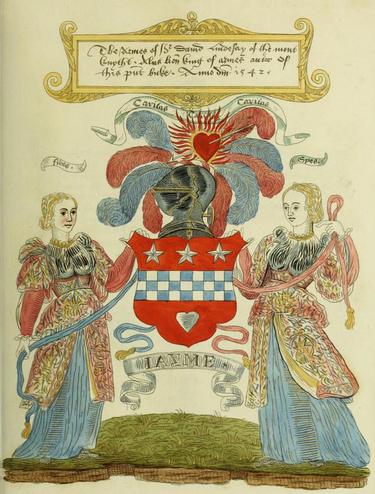

His most immediate care-giver was Sir David Lindsay of the Mount who was a surrogate father, carrying James in his arms, teaching the little boy to dance and play the lute, and telling him stories. James also had official tutors, the poet, Gavin Dunbar, who remained in post until 1525, John Bellenden, Archdeacon of Moray and William Stewart, a scholar.

James, though he proved to be a shrewd and intelligent man, was not academically inclined. Unlike his Tudor cousins, Mary I, Elizabeth I and Edward VI, he had little skill in languages. He was, however extremely musical (although with a poor singing voice) and able to write poetry in Scots. His chief prowess was in the knightly and athletic accomplishments of the mediaeval king – hunting, jousting, and running at the ring. In later life, he also showed an appreciation of material beauty and architecture.

By early 1517, Albany was itching to get back to France. He had left his extremely rich wife, Anne, Countess of Auvergne, and his children behind, and he was also eager to take part in what Francois I hoped would be a continued series of victories in Italy over Imperial and Spanish forces.

Albany nominated a Council to govern in his absence, with Sir Antoine d’Arcy, the “White Knight” as his deputy. D’Arcy was well-known in Scotland, having taken part in James IV’s tournaments. On arrival in France, Albany was able to negotiate a new treaty in favour of the Franco-Scots "Auld Alliance". The Treaty of Rouen of 20 th August 1517 committed both countries to mutual aid against any attack by England and also agreed a match for James with a French princess.

Just before Albany’s departure, Queen Margaret returned from England, with her daughter by Angus, Lady Margaret Douglas. She was allowed to see James, but he was not permitted to live with her.

Albany’s Council of seven soon fell out amongst themselves. D’Arcy was assassinated on 17 th September 1517 by the adherents of the Lord Chamberlain, Lord Hume, and replaced as deputy-Governor by the Earl of Arran, next in line to the throne after James and Albany (the little Duke of Ross having died in early 1517). This went down very badly with the Earl of Angus, who, whilst living with another woman, and flagrantly spending Margaret’s money, still thought he should be in charge of his step-son’s Government.

Eventually Angus and Arran came to open blows at the Battle of the Causeway, which was a running battle along the High Street of Edinburgh on 30 th April 1520. During the fracas, various members of the Arran party were killed. This fanned the flames of the feud between the Douglases and Hamiltons, Angus’ and Arran’s kin respectively. Angus’ relationship with Margaret had also broken down completely, and she sought a divorce.

In November 1521, Albany returned, and Margaret now gave him her complete support – he had proved a far more respectful and considerate friend than her brother or her husband. Henry VIII moved between alliances with France, which was generally positive for Anglo-Scots relationships, and with the Empire, which was not.

Additionally, as the 1520s unrolled, Henry was becoming more concerned about the lack of a male heir. If female inheritance were disallowed (English law did not prohibit it, but it was not a welcome notion), then James V was his uncle’s nearest male successor. Henry would always see James in the light of this unwelcome slur on his masculinity.

Angus was banished to France, and rumours spread that Margaret and Albany would marry. Henry VIII add fuel to the flames with an offensive letter to the Estates, claiming that James had been put in the care of a stranger of ‘inferior repute’ and that Albany’s supposed intention to marry Margaret would put James in danger. Margaret was incensed and wrote a stiff reply, pointing out that if Henry continued to be hostile, ‘the world will think he aims at his nephew’s destruction’ – a pointed dig at a man who was Richard III’s great-nephew.

The Scots Council, led by Archbishop Beaton, also responded questioning the possibility of amity between the countries if Henry continued to undermine Albany. Nevertheless, the Scots nobility was not interested in involvement in large-scale military action against England and many of them were very interested in the bribes and promises liberally scattered around by Henry’s warden, Dacre.

There were large scale border raids led by the Earl of Surrey and Dacre in 1523 in which Jedburgh was attacked and Ferniehurst Castle burnt. Albany was losing his grip on events, and perhaps any will to continue in his role, without more support from the Scots nobles. It was a thankless task, and he left once more for France in 1524, claiming that he had left the country in ‘excellent order’ and might return at any time. In fact, he never returned to Scotland although he still took some part in Scottish affairs abroad, particularly in the early 1530s in relation to James’ marriage.

Angus now returned to Scotland. From France, he had gone to England where he and his brother, George Douglas, struck up an even closer alliance with Angus’ brother-in-law, Henry VIII. For the remainder of James V’s reign, Angus and his brother remained in the pay of the English, and promoted English interests, certainly over French interests, and frequently, it would seem, over Scottish interests. It is, of course, possible that they genuinely have believed that a Scotland subjected to English overlordship was a desirable outcome for the country. Henry VIII consistently favoured Angus and his plans over those of Queen Margaret.

Despite their failed marriage, both Margaret and Angus wanted to promote James as old enough to rule without Albany as Governor. The English, too, were in favour, seeing it as an opportunity to keep Albany and the French out. The obstacle to the plan was James Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrew’s who remained wedded to the French alliance. Henry, and his chief minister, Cardinal Wolsey, hatched a plot with Lord Dacre to kidnap Beaton, on the pretext of Beaton attending a conference to settle matters on the border.

Beaton was too shrewd to fall for it and proposed sending others in his place. As the English had never really intended a peace conference, the idea was abandoned now that the object of capturing Beaton could not be fulfilled. Henry continued with his plans to bribe Scotland into submission, sending money to Arran, and to Margaret and paying for a bodyguard for James.

On 26th July 1524, James and his mother rode from Stirling to Edinburgh where the nobles swore allegiance to the King, and on 20 th August the Estates declared the Governorship of Albany to be ended. James had turned twelve that spring.