Palace of Placentia

by Nicholas Wood

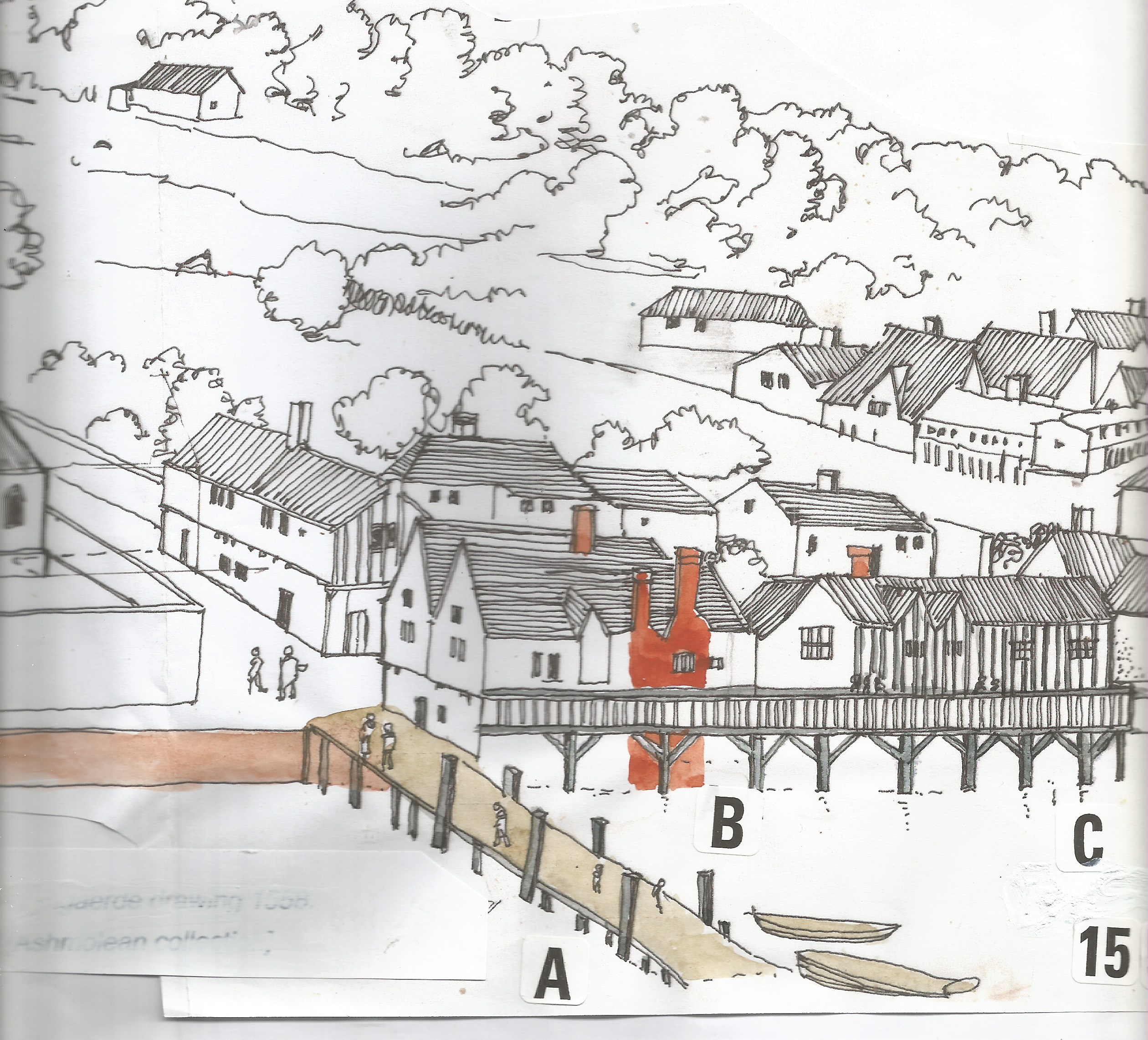

Placentia was Henry VIII’s and Queen Elizabeth’s favourite palace stretching 200m along the foreshore on the great sweep of the Thames, with splendid views of their ships, and backed by the hunting forests of Blackheath, and the old Roman Road to Kent.

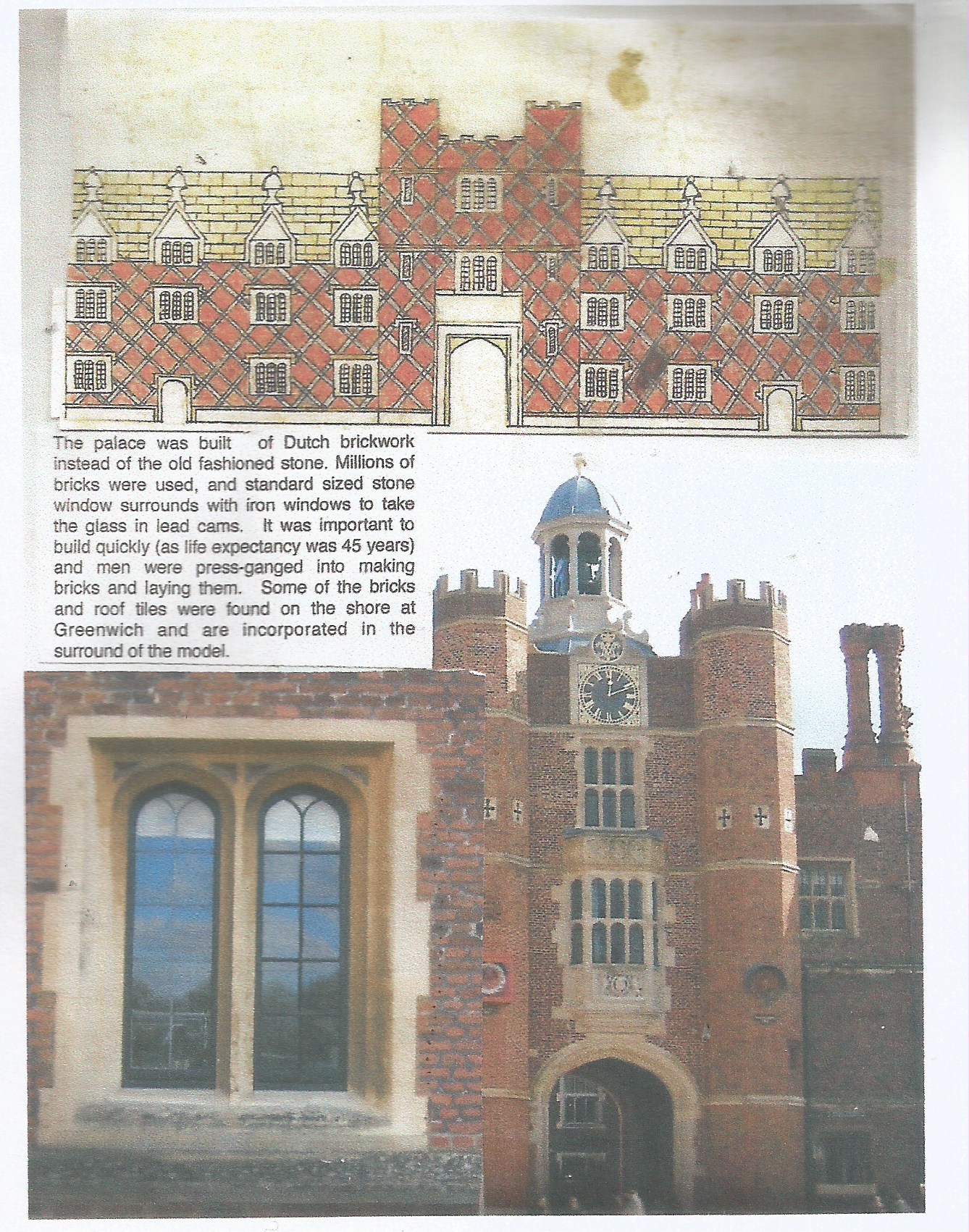

There is tragically nothing left of the Placentia Palace at Greenwich. It was demolished as an ugly old fashioned building in ruins by Wren and Hawksmoor to make room for their Greenwich Hospital. They adjusted the angle of the river wall and levelled the palace to make way for the grass lawn between the main buildings, throwing old bricks, tiles and stonework and other rubbish into the river. Wren had also wanted to demolish Hampton Court to make way for his rather dull building for William and Mary. Fortunately they ran out of money.

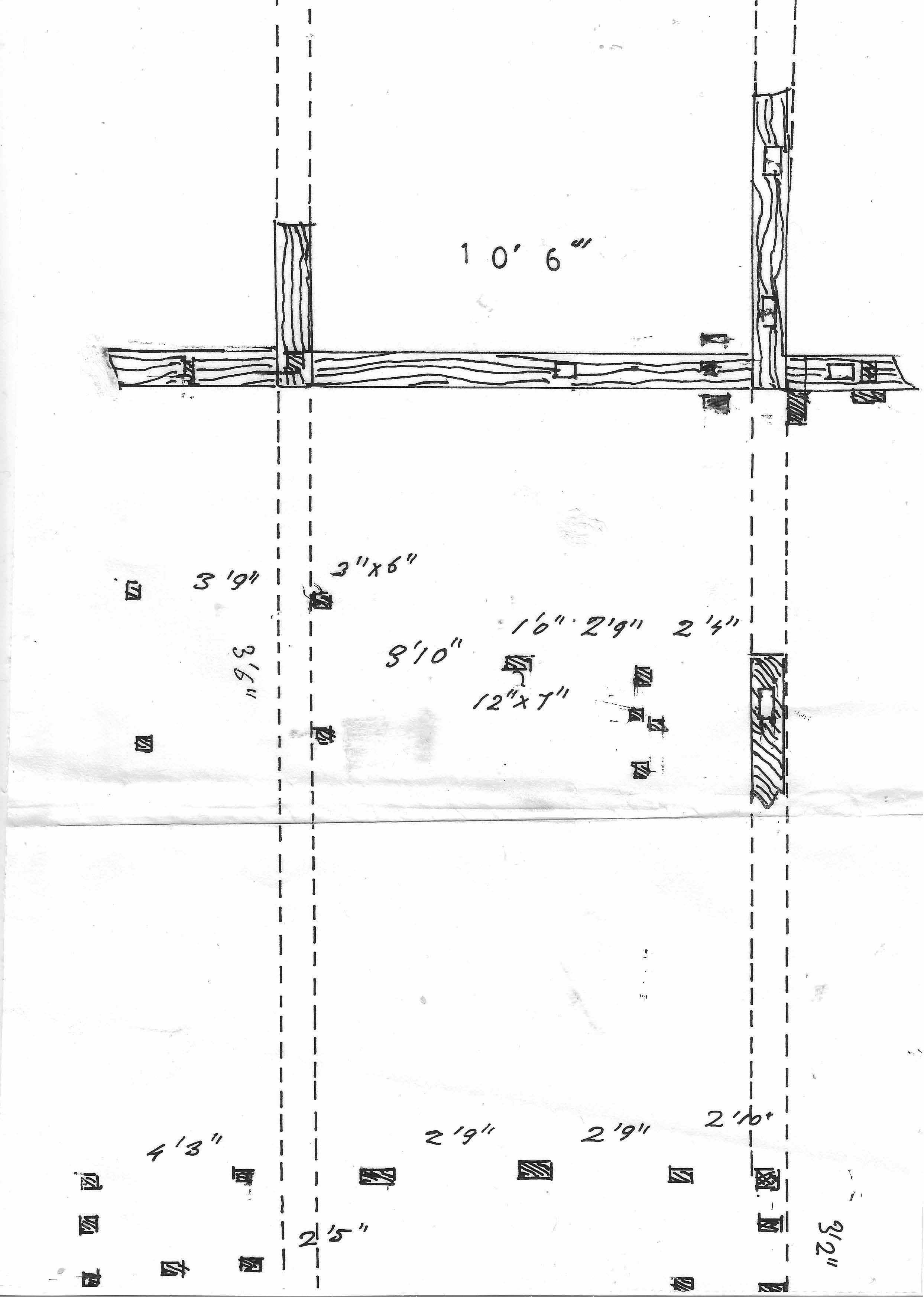

Five years ago, I noticed some timber posts and beams poking out of the mud along the Greenwich shore stretching down to the water’s edge at low tide. The new fast ferries at Greenwich have been eroding the shore revealing the timbers.

The London Museum confirmed that they were indeed Tudor and were part of the Henry VIII‘s Pontoon. I measured and surveyed their levels and studied Wyngaerde’s 1558 long drawing of Placentia Palace and the ramp down to the Thames. [A] There were also timber frame buildings with brick chimney stacks along the river wall. It was exciting to find the bases of these in the mud in the exact location shown on the drawing. [see D and B-C]

In the sand and mud along the foreshore there were also large numbers of Tudor artefacts: green glazed pottery, Bellarmine beer pots from the Rhine, bones of boars, lamb, chickens, beef, and oyster shells and other rubbish, thrown off the pontoon near the kitchens four hundred and fifty years ago.

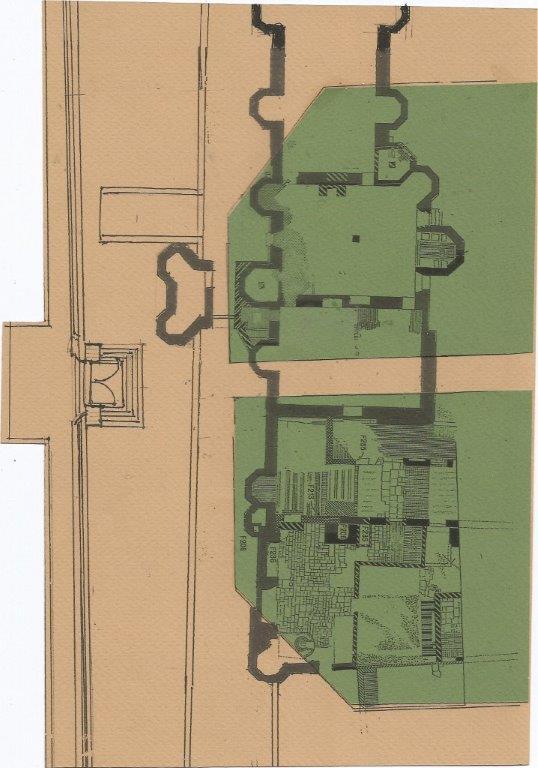

The Maritime Museum has been asked to confirm that this was the base of a quadruped navigation beacon to shine a light at night to guide sailors to the pontoon. A flaming beacon would be dangerous to sailing boats if it were sighted actually on the pontoon. There was a 1.5 m gravel path leading towards this structure from the shore which is now washed away. Leading down to the shore are timber piles in two rows 6 m apart, and slotted bases of uprights circa 10 m apart. These correspond to the pontoon shown on Wyngaerde’s 1558 very precise drawing of this area. Wyngaerde also drew the long Placentia Palace building where doorways and towers correspond exactly with positions in the archaeological excavation of 1971. From the perspective of his drawing it would seem that he made the drawing from a crow’s nest in a ship anchored in the Thames.

Tragically nothing is left of the actual Placentia Palace. This was one of the most important Tudor Palaces. It was where Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth were born. It was constructed as a bastion by Henry VII under the direction of his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, an ambitious, very wealthy, pious, and ruthless woman. She realised after the Battle of Bosworth the first thing for her son to build was a defensive bastion. Henry used the stone foundations of an old farm house including the two kitchen chimneys, built by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, when he was Regent as brother of Henry V.

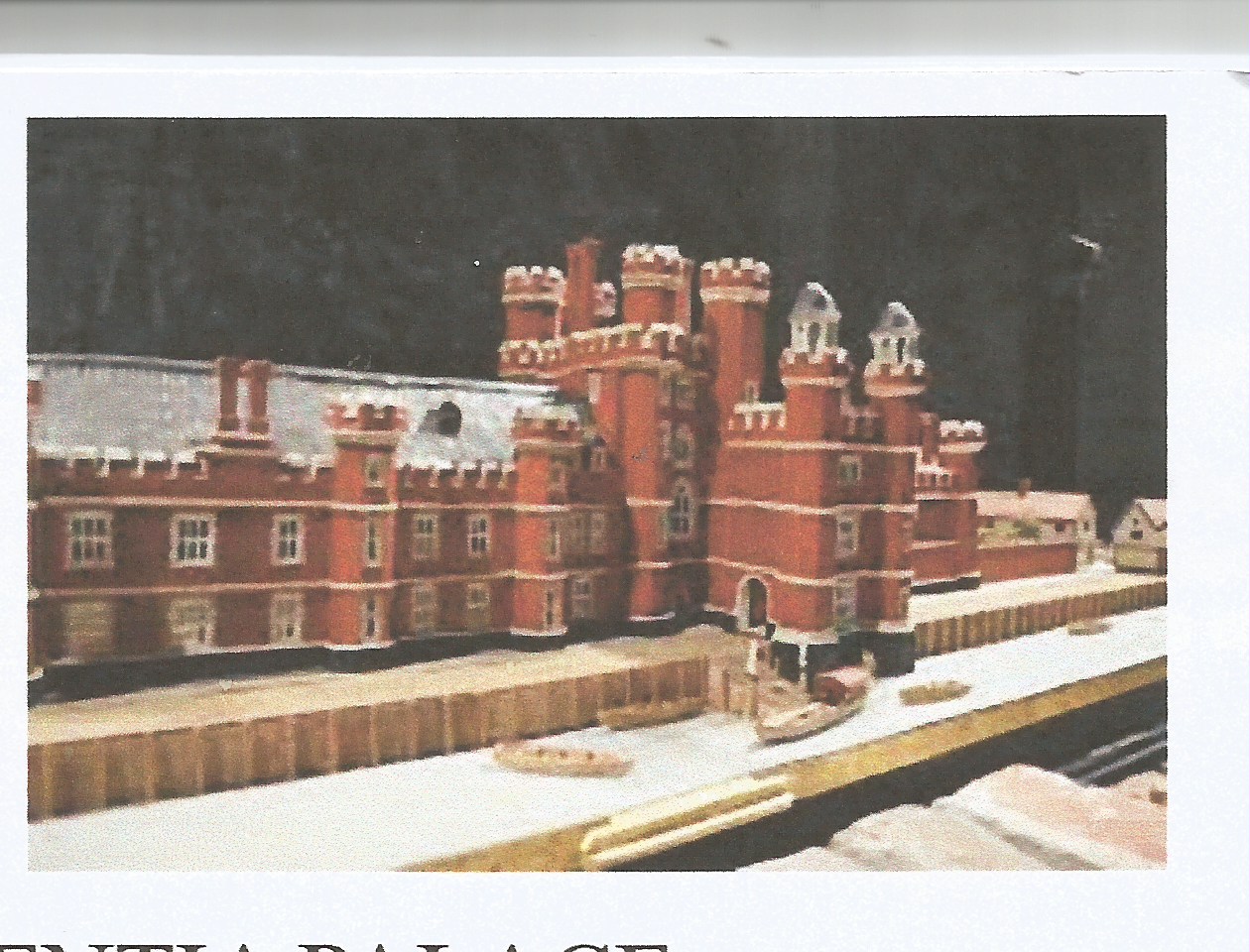

I decided to make a model of the palace, and so that it was as accurate as possible, the Clerk of Works of Hampton Court Palace kindly let me go into the roof spaces and measure the timbers, brick walls and stone windows. It soon became apparent that Tudor buildings of this period were standardised for speed of construction, and simplicity of contracts. The window surrounds, for example, are all the same for one, two, or three light windows holding iron frames and lead lights for glass. This standardisation was to make it possible (since life was short = about 45 years) to build these large palaces and colleges of Eton and Oxford and Cambridge within 4 years with indentured, and even press ganged, labour. Lime kilns, and bricks fired in clamps, were operated on site, guided by teams of Dutch bricklayers. The contract drawings for St. John’s College, Cambridge, built from 1511 onwards, are simple diagrams of doors, windows and staircase towers: almost a code.

The Clerk of Works also showed me, in the six foot gap between Wren’s building and the end of the Tudor Dining Hall, the extraordinary brickwork painted in iron oxide colour wash (ruddled) and black diaper pattern header bricks,[as at Richmond Palace, see illustration] and a black three foot dado. This showed how garish the Tudor Palaces really were. I have reluctantly painted the model in these colours with their Lewis Caroll playing card quality, as exhibited in the Hampton Court gardens with their geometric herb beds marked on each corner by Royal Beasts painted white and mounted on poles.

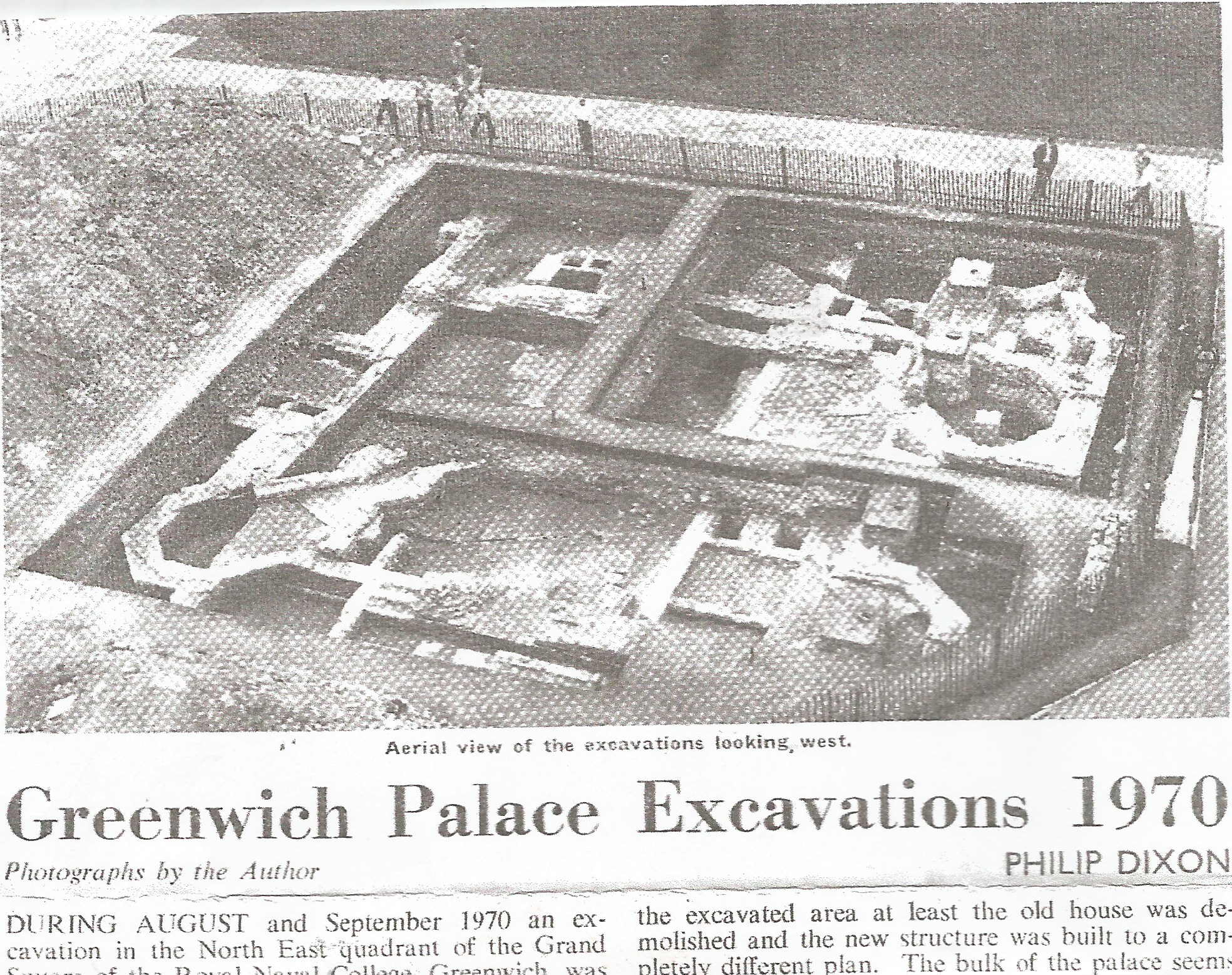

The archaeological excavation in 1971 revealed much of the central floor plan of this palace.

There were some fascinating things which showed that in the main bastion tower there were lavatories with 6 seats above the large sewer running into the Thames. This sewer would have been cleaned at night by small boys called gong scourers but it meant that, like the Romans, Tudors did not mind easing in communal lavatories. [There is one at Hampton Court with 28 seats.] The remains also showed that the main bastion was added to, with a small tower and doorway, to provide security on the riverside path. At the further end of this riverside path was the treadmill crane operated by men walking inside a drum. This would have been the main crane for off-loading goods for the palace. There is a street near by today which is still called Crane Street.

Conclusion

There are three objects of this article:-

Firstly : to recognise that Placentia Palace at Greenwich was of extreme importance even though there is nothing visible today.

Secondly: to show the possibility of an outline of the palace, flush with the grass and paving of Wren and Hawksmoor’s Royal Hospital. This can be based on the 1971 archaeological excavations of the foundations and be built in brick, or clay tiles, or granite setts. This will enable visitors to be aware of the size and significance of the Palace.

Thirdly: to prevent the erosion and loss of Tudor structures on the foreshore of the Thames at Greenwich. These are fast being washed away by the high speed ferries from Greenwich pier. They could be protected by steel mesh bags of broken concrete to break the power of the waves.

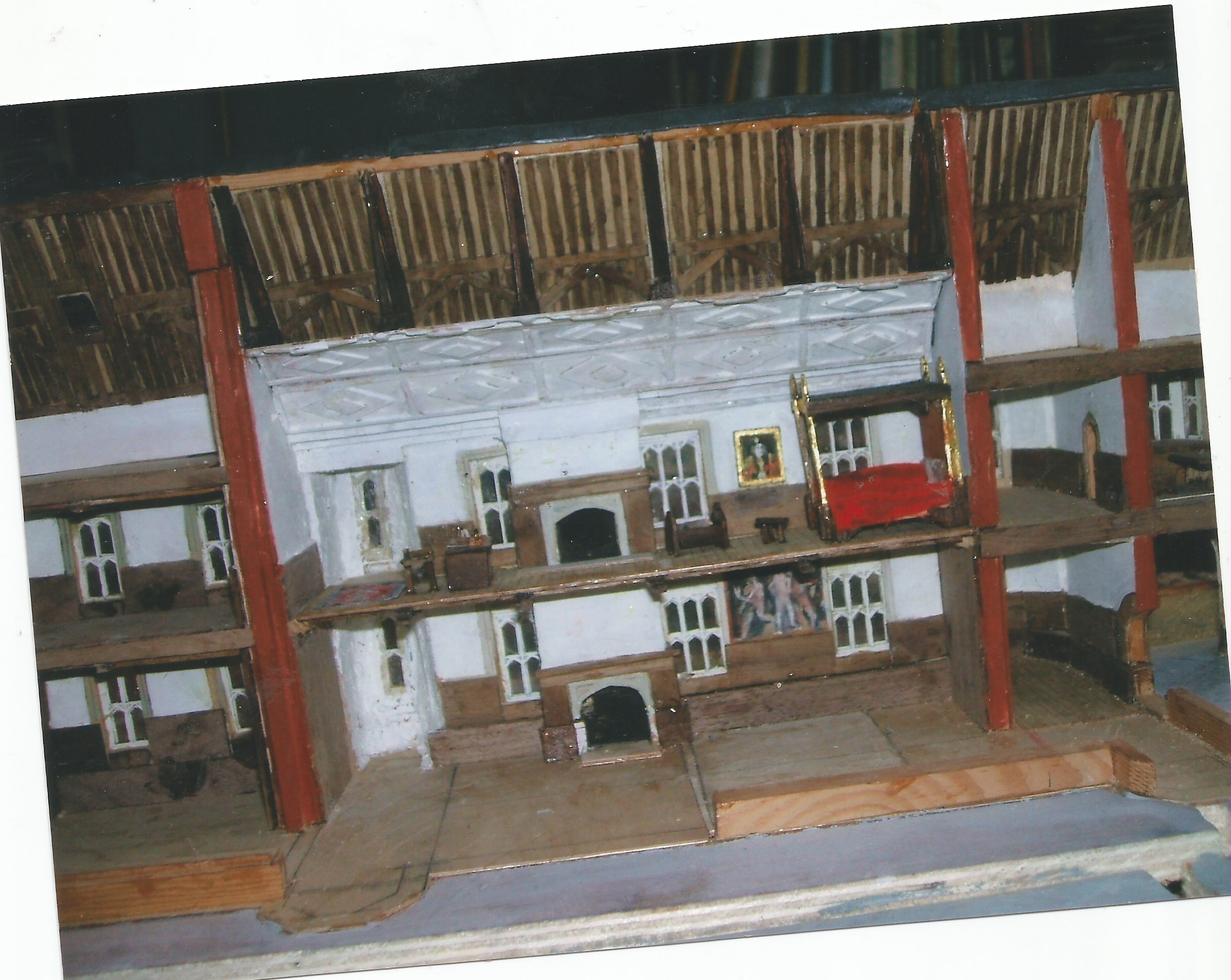

The model in the 1601 Crypt, a hands on educational experience.

The model is sliced in half to show the interior of the rooms:- the big kitchen chimneys, like at Hampton Court, with hooks for smoking the hams of pigs; the staircase up to the dining hall; Henry VIII’s chapel, his chess board, and, in one of the bedrooms, baby Elizabeth’s cot; and, in an audience room, miniatures of Tudor paintings and carpets based on the “Ambassadors” 1533 painting in the National Gallery.

Around the model there are fixed samples of Tudor pottery which were found in the mud:- bones of animals and birds that were eaten, bricks and roof tiles, fragments of stone window surrounds and floor tiles so that children can touch these objects, and associate the finds with the model porringer bowls in the kitchen of the model. Now there are hardly any remains left to be seen on the beach as they have all been washed away.

Also there are, in slots, educational boards which can be pulled out, with such questions as “How long did it take for Anne Boleyn to be rowed from the Palace to the Tower of London, 3 miles away, if there was a 6 knot flood tide, and the rowing boat could be rowed at 6 knots? How long would it take to row to the Tower on the ebb tide?

The model, 6 feet long, was difficult to make. Each tower has 82 tiny pieces of wood cut out and glued together, and the roofs are covered in real thin lead sheets. The scale for the chess set was difficult. Having glued the stone artefacts to the surround, it then took 6 men to lift the model, first out of my window, which had to be removed, and then, miraculously, into the Crypt at Greenwich, without any damage.

Other Hidden Remains of the Palace - the Tiltyard

Tony Robinson, with his “Time Watch” team, showed where, in the east corner of Greenwich Hospital, were the Tilt Yard and the two observation towers. In the three days, his team even found the sand of the course and a horse shoe. In the west side there were iron traces of Henry’s German armoury. At the east end of the site, the Wyngaerde drawing shows a tread mill crane on the shore, operated by men treading inside the wheel. This was near the little road which is now called Crane Street.

View of the model which is housed in the only remaining 1601 Tudor building , the crypt, is by appointment only.

The original Wyngaerde 1558 drawing can be seen in the Ashmolean Museum,Oxford.