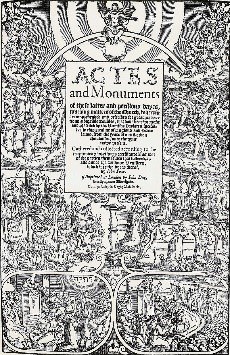

The Book of Acts and Monuments

Chapter 2 : The Book

Acts and Monuments was described by Foxe and Day as a work that would ‘[touch] the full Historie, processe and examinations, of all our blessed brethren, lately persecuted for righteousness’ sake’. Despite it being thought rather unscholarly to publish other than in Latin, English (other than for the preface) was to be the medium to help spread the message amongst the laity.

The first edition was in five books – the first covered the period from the early Church until the late thirteenth century, including the death of Thomas Becket. Foxe disapproved entirely of the cult of the archbishop, particularly criticising the idea that Becket’s death or intercession might help others to salvation. By the end of the thirteenth century, he recorded, England was in ‘thraldom’ to papal authority – although its case was not so dire as that of the Empire under Frederick II, who was persecuted up hill and down dale by successive popes.

The second book covered the period of Wycliff and the Lollards, the death of Sir John Oldcastle, the Hussite wars in Bohemia, and the various Church Councils of the fifteenth century. Much of the content of this section was translations of other accounts.

Book three continues the history of the fifteenth century, and moves into Foxe’s own century. It gives a detailed account of the famous case of Richard Hunne, then moves on to Luther. He worked through the whole reign of Henry VIII, giving a detailed account of the martyrdom of Anne Askew, based on the work published by Bale in 1546.

The fourth book is devoted to the reign of Edward VI, whom he praised as ‘a prince in al ornamentes and giftes belonging to a prince incomparable, derely and tenderly beloued of all his subiectes, but especially of the good and the learned sort, and yet not so muche beloued as also admirable, by reason of his rare towardnes and hope both of vertue and learning whiche in hym appeared aboue the capacitie of his yeares.’

This section also includes the correspondence between King Edward and his half-sister, the Lady Mary (afterwards Mary I).

The final book is dedicated to the ‘Ecclesiasticall historie conteynyng the horrible and bloudye tyme of Queene Marye’ and begins with a disquisition on the evils of the Mass. It then describes the accession of Mary, and reviews her reign, detailing the martyrdoms, in a volume of pages equal to the previous four books. The book was illustrated with numerous graphic woodcuts.

The first edition retailed at somewhere between 10s and 15s – at least a month’s wages for a skilled worker. Nevertheless, it sold well. Unsurprisingly, it provoked strong reactions – Archbishop Parker thought that the many quiet Catholics who still abounded in the first years of Elizabeth’s reign were horrified by the persecutions described, whilst others reacted with rage against what they saw as inaccurate descriptions of their own or a family-member’s role in them.

Still others sent Foxe more information on new aspects of recent history, and much of this was incorporated into the second edition of 1570, which was significantly changed from that of 1563. It was much longer, even though certain parts were removed in response to the barrage of criticism the earlier edition had received at the hands of Catholic writers, and ran to some 2,300 large pages, bound in two volumes. The 1570 edition was also far less laudatory of Elizabeth, who was not proving to be the Protestant heroine that Foxe had hoped for – she was pragmatic, cautious, and disinclined to allow religious policy to be the arbiter of political action.

In April 1571, Convocation ordered all Cathedrals to have a copy of the book, and encouraged each parish church to do so as well.

The 1576 edition was a cheaper version of that of 1570, but the fully revised and cross-referenced edition of 1583 was an enormous pair of volumes, produced to the highest quality and containing some 2 million words. It was an expensive, and staggeringly labour-intensive production.