The Book of Acts and Monuments

Chapter 3 : Editions after Foxe's Death

The wide dissemination of the book, together with increased government polemic against the Catholic church, particularly as part of the war with Spain that dominated the latter half of Elizabeth’s reign ensured that Acts and Monuments entered deep into the psyche of Protestant Englishmen and women. The fear and suspicion in which Catholicism was held from the 1580s right up until the modern era, grew, in part, from Foxe’s writings, especially as they were abridged by Thomas Bright in 1589, who gave them a distinctly nationalist flavour.

Further editions were published in 1596 and 1610 (Edward Bulkeley), with extra information about the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre and the Gunpowder plot, respectively. These might be considered continuations. In 1632, however, with a widening divide between the established English church, which, whilst still fundamentally Reformed in doctrine, was seeing a renaissance of the ceremonial side of religion under Archbishop Laud, a new edition of Acts and Monuments was published.

This added an entire section, entitled ‘A treatise of afflictions and persecutions of the faithfull, preparing them with patience to suffer martyrdome’. This was aimed at the here-and-now, and the likely martyrs were the Puritans, who were resistant to Laud’s reforms, for which he had the support of the Protestant, but beauty-loving king, Charles I. Rather than the English church being the true church, it was apparent that the Godly would always be prosecuted.

In 1641, as the British Isles declined into the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, yet another edition was published, containing a biography of Foxe, translated from an earlier draft by his son, Simeon. Foxe had never advocated rebellion against a lawful prince, but he was now co-opted into the Puritan resistance to Charles I. This edition was treasured by Milton and Bunyan, but, with the return of the monarchy and a Laudian view of Anglicanism in 1660, Acts and Monuments was no longer revered by the ruling class.

The last flourish for Acts and Monuments was a ninth edition at the time of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 - a triumph of Protestantism in an age when the heat of religious dissent was dying down, but Catholicism was still viewed as a political threat, with the power of Catholic France continuing to grow.

Derivative editions appeared in the eighteenth century, often with a voyeuristic or pornographic edge. Frequently, the wider history was removed, leaving little more than descriptions of persecution and anti-Catholic polemic. This narrow nationalism contributed to the anti-Catholic feeling of the eighteenth century, expressed openly in the Gordon riots of 1780 and the long resistance to the relaxation of the Test Acts (the requirement for holders of public office to take communion in the form prescribed by the Church of England – excluding Catholics and Dissenters, not repealed until the Catholic Relief Act of 1829).

John Wesley, the great Methodist leader also edited Foxe, removing most of the history, but also avoiding the anti-Catholic strains, concentrating instead on the vision of two kingdoms – the earthly and the heavenly.

In the nineteenth century, Acts and Monuments received a new lease of life. It was an age more explicitly religious than the previous century, and the Anglican church was once again riven with strife between its Evangelical wing which emphasised the Reformed nature of Anglican belief, and the High Church party, which saw the Anglican church as the true successor to the ancient Catholic church, unsullied by Rome.

The former group saw Foxe’s work as foundational, and a new edition was printed, edited by the Evangelical Rev. George Townsend in 1837 – 41. It was criticised by the High Church party, in the person of S R Maitland, Librarian of Lambeth Palace – at least in part on the grounds that Acts and Monuments was not unbiased history and also because of Foxe’s ambivalent views on episcopacy and his support of the Knoxians in the Geneva controversy.

Matters were further complicated by the emergence of the Oxford Movement, which sought to emphasise Catholicism within the Anglican church, adherents of which were often critical of the early Reformers and of Foxe. Any sympathy with their arguments was seen by the Evangelicals as the high road to Rome.

Further excerpts, bowdlerised and adapted editions followed though the century and were praised or criticised within the Anglican church, depending on the viewpoint of the commentator. The renewed interest in Foxe by the Evangelicals led to a spate of memorialisation of the Marian martyrs in monuments around the country. See more here.

This was enhanced by the various Protestant Association, including the Birmingham Protestant Association which produced martyrologies based on Foxe at prices from a penny to 2s 6d. Birmingham even produced a magic lantern show, from illustrations in Acts and Monuments, to be taken to schools to keep the children aware of their duty to the Protestant faith, and argue against the evils not just of ‘popery’ but of ecumenicalism.

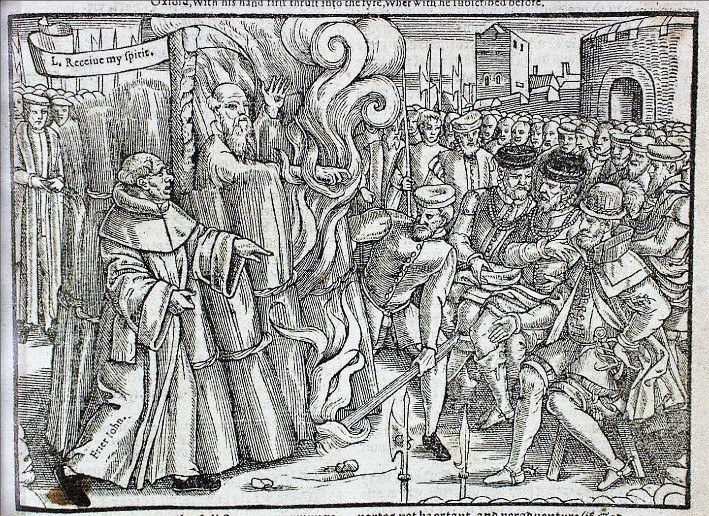

Over the course of the twentieth century, religion ceased to feature as a matter of great concern for most British people. No-one, other than historians, now reads Foxe, yet his work still forms the basis of many histories of the period – the martyrdom of Anne Askew, the conspiracy against Queen Katherine Parr by the conservatives at Henry VIII’s court, the burnings of Cranmer, Ridley, Latimer and Hooper and much else derive only from Foxe.

But Foxe was not a neutral historian (in so far as a historian can ever be neutral). He did not see that as his role. His writings were designed to encourage the Godly and expose the evils of the ‘papists’. Modern scholarship has shown that Foxe was accurate in his presentation of facts, but that he ignored entirely facts that did not support his arguments, giving a one-sided view of events. He was a polemicist, rather than a sober presenter of balanced views, so when using him as a source, we must always bear in mind, that he is only presenting half the picture.