Burghley House

An Elizabethan Prodigy House

Chapter 2 : Kitchen & North Range

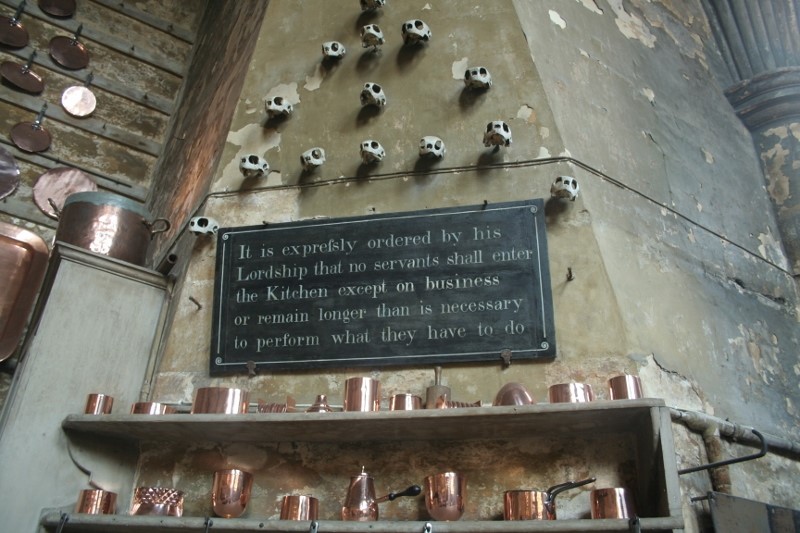

On leaving the ticket office, you will find yourself in a small (by Burghley standards!) courtyard, with lavatories and a shop. The entrance to the house is in the south west corner. It is by no means imposing, and, in fact, it leads directly into the original Elizabethan kitchen. This is a fantastic space – at least thirty-foot high, with a central lantern, originally designed to draw smoke up, but now allowing in light.

There were originally two enormous fireplaces which in later centuries were partially filled in with ranges and other more modern cooking appliances. The kitchen gleams with the most fabulous display of copper pans I have ever seen – well over 250 of them! On a less appealing note, there is a collection of turtle skulls on the wall – presumably the creatures ended up as turtle soup, a Victorian delicacy. This was my favourite room in the house, as it is one of only two that are in any way Elizabethan.

Through the kitchen is the ‘Hog’s Hall’ (no, I have no idea why it is called that). In it are the bells to summon the servants to any of the multifarious rooms. There is a hall porter’s chair (a curved back enclosing the sitter) in which, presumably, some lucky lad sat all day to identify which bell was being rung so he could send the butler to the appropriate place. In this room are also housed the old-fashioned leather fire buckets (you will have seen similar ones in the Downton Abbey episode when Lady Edith’s room catches fire).

The Hog’s Hall gives on to the Roman Staircase, which is a gem of Elizabethan Renaissance architecture. The coffered ceiling and Tudor emblems are a delight.

After these stairs, the remaining rooms open to the public were all renovated during the centuries following Lord Burghley’s death, with the majority of the décor dating from the late seventeenth century. Whilst the number of rooms open to the public is not extensive, in the context of the whole house, they are all unremittingly grand, ornate and stuffed to the gunwales with pictures, objets d’art and superb furniture from generations of exceedingly wealthy Cecils, who regularly indulged in Grand Tours.

Much of the art is Italian, from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and represents the Counter-Reformation in all its glory of fat cherubs, writhing saints (often with rather grubby faces) and plumptious pagan gods being overcome. I couldn’t help thinking that Lord Burghley would be getting a bit hot under the ruff with the various Catholic accoutrements around the house. One item that might have delighted the Classical scholar in him is a mosaic, believed to be a genuine Roman article. It is quite amazing, thousands of very tiny pieces of ceramic, forming a bird.

The first room along the north side is the Chapel, with an astonishing altarpiece by Veronese, purchased by the 9th Earl from the Island of Murano, in the Venetian Republic. God the Father is at the top, emerging head first from a cloud, with supporting angels, whose life-like legs seem almost to erupt from the surface of the painting. The rest of the Chapel is in the style of the late 1700s, although there are some carvings from followers of Grinling Gibbons. It is usually possible to see out of the Chapel ante-chamber window into the central courtyard, but scaffolding prevented this during our visit.

Following on from the Chapel are the Billiard Room, the Bow Room (superb drum table), the Brown Drawing Room, and the Black and Yellow Bedroom. This latter has a bed slept in by the Duke and Duchess of York, later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. It looks grand, rather than comfortable.